Senior U.S. Air Force officials have provided new details about the service’s vision for integrating an evolving set of autonomous capabilities onto new uncrewed aircraft, as well as the groundwork that has already been laid through various recent testing initiatives. The Air Force views advances in autonomy as absolutely at the core of its plans for a forthcoming fleet of drones designed to work collaboratively with crewed platforms. However, humans are expected to remain heavily ‘in the loop’ for the foreseeable future when it comes to certain sensitive tasks, especially decisions about whether or not to employ lethal force.

This new information about what the Air Force is currently referring to as the Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) effort came during a roundtable at the Pentagon that The War Zone and other outlets attended yesterday. CCA is a part of the Air Force’s broader Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program, which includes work on advanced stealthy crewed and uncrewed aircraft, as well as sensors, networking and battle management capabilities, weapons, next-generation jet engines, and more, as you can read more about here.

“We’re in a transition phase to bring in a new capability to the Air Force that’s more revolutionary than evolutionary,” Maj. Gen. R. Scott Jobe, the Director of Plans, Programs, and Requirements, at Air Combat Command (ACC), said at the roundtable. “There’s a lot of interesting things that CCA with a lot of autonomy brings to the fight.”

“One of them is your ability to manage risk in different ways that we’ve not been able to do before,” he continued. “So, if you get into any sort of air combat engagement, you get to a certain point where… you have to either make a decision on survivability, either pro or against yourself… and so it’s not a very good position to put a human American pilot into.”

Though the Air Force says its current CCA requirements are classified and that potential budgets and schedules are still being finalized, Maj. Gen. Jobe added that the expectation is that these drones will bring “a lot of potential capability at a lower price that we hadn’t seen before.” The service has indicated in the past that at least some of the uncrewed aircraft designs within a potential future CCA ‘system of systems’ could be ‘attritable.’ This term is typically used to describe aircraft and other major weapon systems that have been developed with a specific eye toward balancing cost and capabilities to the point that the platform could be more freely lost in combat, especially, at least in some cases, so that higher-end, more ‘exquisite’ platforms could survive.

Jobe further elaborated that being able to approach risk in new ways with future CCAs opens up a path to being able to think very differently about tactics, techniques, and procedures in future aerial combat.

“We know we’ve got pretty good ability to do auto take off and land. So that’s a pretty simple behavior. Auto-routing and fuel planning, we think that’s pretty good,” Jobe said in talking about the current state of autonomous capabilities for uncrewed aircraft available to the Air Force. “I can do a lot of mission planning type of activities. I can also do some formation station keeping.”

A fighter pilot can “basically tell it [a CCA-type drone] with some pretty easy pilot-vehicle or human-machine interface [to] ‘fly formation off me’ and have parameters already established,” Jobe offered as an example of a collaborative behavior that is well established now. The Air Force is already exploring technologies and associated concepts of operation around having CCAs do much more than this, including firing weapons at enemy forces. Of course, when it comes to actually employing lethal “effects,” and even potentially some non-kinetic ones that might present serious risks to innocent bystanders if used inappropriately, a human is still expected to be the final decision maker for the foreseeable future.

However, “we just don’t see a path right now, for us to field a capability that both is effective in its warfighting capacity, but also supports American values and the Law of Armed Conflict,” Jobe stressed. “I’m not going to have this robot go out and just start shooting things. That’s not something that we’re going to do.”

Jobe noted that future autonomy developments could potentially “spill out” and be integrated together with the flight control and mission systems on crewed aircraft, too. He described his own experience attacking targets on the ground in Afghanistan and how autonomous capabilities could have reduced his workload by automatically determining an optimal route and otherwise helping to get the aircraft into the right position relative to the threat.

“We’re gonna see a lot of that cross-pollination of tech out of CCA,” he said.

There is also a hope that eventually the process of developing and refining the underlying software to support autonomous aircraft capabilities will be so fast that it can be done right in the midst of actual operations. The Air Force, among others, has also stated its interest in this kind of rapid software development to support electronic warfare capabilities, as part of a concept currently referred to as Cognitive EW, which you can read more about here.

“Something that we have never really even thought about before, in a typical fighter squadron, is do I need a data scientist, a coder, and an intel person who’s digitally savvy to bring in all of the data that comes off of one of these, and then reprogram some behaviors to be smarter, like from the first go of the morning to the first go of the night,” Maj. Gen. Jobe said.

So, what we want to be able to do ultimately [is] code in the morning, fly in the afternoon,” Maj. Gen. Heather Pringle, head of AFRL, added. “Frankly, even faster than that” would be desirable, she added.

The Air Force and other elements of the U.S. military have, of course, already been working on developing autonomous capabilities for crewed and uncrewed aircraft for decades now publicly, and there has all but certainly been significant work done in the classified realm, as well.

Still, the Air Force has initiated a number of new lines of effort in recent years that it says have been especially valuable in further maturing relevant technologies. The most prominent public project in this regard has been Skyborg, a shared effort between AFRL and the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC), which centered on the development of an artificial intelligence (AI) driven “computer brain,” along with associated systems, which could be used to provide various degrees to different types of aircraft. You can read more about Skyborg here.

“There was an autonomy core system that was part and parcel to Skyborg, and this is really the algorithms that enable these aircraft to fly,” Maj. Gen. Pringle said. “Through partnering with warfighters, with the developmental test community, the operational test community, we located some of our personnel down at Eglin to look at how these algorithms would be flying on a number of different aircraft – not just one type of aircraft, but multiple different ones – so that these software programs, this autonomy core system would – we’d really work out the kinks and get something that would be more useful in the long run.”

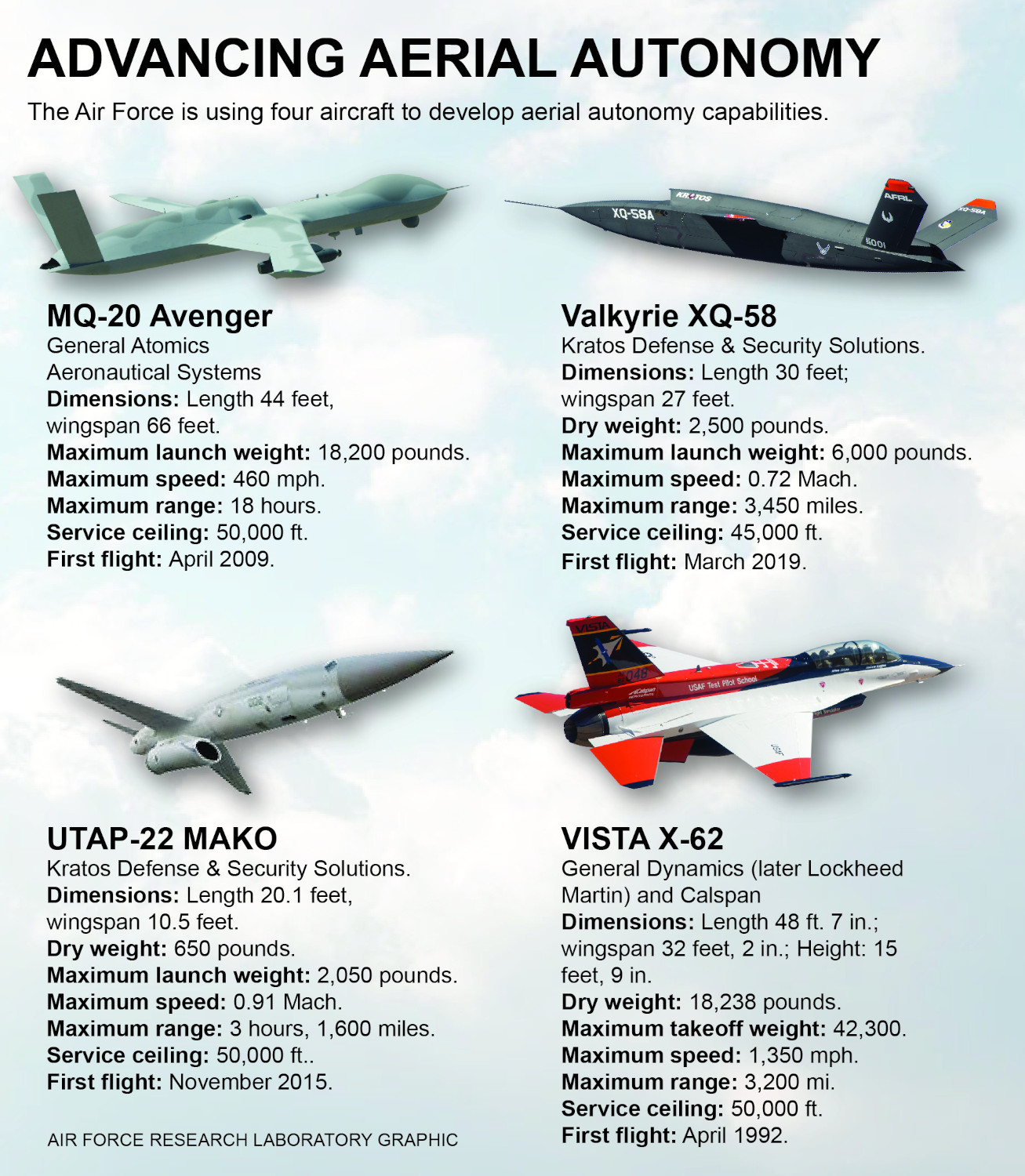

To date, elements of Skyborg have been tested on three uncrewed platforms, the UTAP-22 Mako and the XQ-58A Valkyrie, both supplied by drone-maker Kratos, and the General Atomics’ Avenger. The X-62A test jet, a heavily-modified two-seat F-16D fighter jet, which you can read more about here, has also been used to support the Skyborg project.

“We did not swing for the fences, we went for a base hit. So I’m not talking about Terminator Skyborg autonomy. We’re talking about real things, real behaviors, and real aircraft,” Maj. Gen. Jobe added in talking about the Air Force’s current focus when it comes to autonomous capabilities. “This is entirely in the art of possible.”

At the round table, it was made clear that projects like Skyborg have also helped the Air Force gain very basic levels of confidence in its ability to conduct routine operations using drones with various degrees of autonomy just as safely and effectively as it does with crewed aircraft. In a similar vein, the service has had to engage with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) about the safety of conducting its autonomy-related research and development and test and evaluation activities within U.S. airspace. Part of the reason why the Air Force is now planning to conduct tests involving XQ-58As flying out of Eglin Air Force Base in Florida is simply to further demonstrate that these drones can operate autonomously with a reliable level of safety within the set boundaries of various nearby test and training ranges.

Already though, the “success I think we’ve had to date with ops experimentation has been pretty game-changing,” Brig. Gen. Dale White, the Air Force’s Program Executive Officer for Fighters and Advanced Aircraft, added. The Air Force is now at a place where “we can mature autonomy in an iterative nature and I think that’s the key. … We’re going to continue to iterate that capability.”

All this being said, the Air Force has now made clear that the Skyborg computer brain, or “autonomy core,” won’t go straight into a future CCA as is. At the same time, the service sees it as a “direct lift” that will feed into the further development of autonomous capabilities for the CCA effort. Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall has previously identified the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Air Combat Evolution (ACE) project and the Royal Australian Air Force’s Airpower Teaming System (ATS) program, the latter of which has already led to the development of Boeing Australia’s MQ-28 Ghost Bat drone, as “technology feeders” for advanced Air Force uncrewed aircraft initiatives.

At the roundtable, it emerged that Secretary Kendall has made clear his desire for the CCA to focus on designs from the U.S. industrial base, and that the made-in-Australia MQ-28 is effectively out of the running as a result. [See update for clarification] This is despite the Air Force, in cooperation with the Pentagon, having recently acquired at least one Ghost Bat to support advanced uncrewed aircraft research and development and test and evaluation activities. None of this would, however, preclude Boeing from building a derivative in the United States specifically to meet the service’s requirements.

No matter how the Air Force ultimately integrates CAAs with any degree of autonomy into its future force structure, the consensus is clear these kinds of uncrewed platforms will be critical in future aerial combat. “We’re convinced that this capability is required,” Brig. Gen. Joseph D. Kunkel, the Director of Plans, Deputy Chief of Staff, Plans, and Programs, at the Air Force’s top headquarters at the Pentagon, said at the roundtable.

“We have a lot of analytical support that shows that this actually changes the way that we fight and makes us more effective in the way that we engage in combat operations,” Maj. Gen. Jobe added. “It’s been in multiple independent studies, which makes us feel highly, highly confident that we’re on a solid path forward.”

It’s not exactly clear what studies Jobe may have been referring to specifically. It is known that multiple wargames that the U.S. military has run, as well as those conducted by independent think tanks working under contract with the U.S. government, have shown that networked swarms of drones with high degrees of autonomy would likely have game-changing impacts in any future conflict in or around the Taiwan Strait, as you can read more about here.

There is, of course, still the potential for the Air Force’s plans for how autonomy will fit into the future CCA program, a competition of some kind around which is set to kick off next year, as well as other efforts. Yesterday’s roundtable highlighted the service’s focus already on an iterative approach to the development of these capabilities.

What is only becoming more and more clear is how central the Air Force views advanced aerial drones with increasing levels of autonomy to how it expects to conduct operations in the future.

Update 11/21/22:

The Air Force has reached out to The War Zone to clarify comments from the roundtable, specifically those made by Maj. Gen. Jobe, regarding the potential participation of the MQ-28 in the future CCA competition.

Ann Stefanek, an Air Force spokesperson provided the following full statement:

“While the nature of the question was related to the MQ-28 Ghost Bat and, by association, our partnership with the Australians, the response was NOT meant to suggest that Ghost Bat or ANY vehicle is exempt from the competitive program for CCA. The context of the response was meant to communicate that the CCA program will be a competition, and to highlight that discussions about ANY vehicle is pre-decisional. As Maj Gen Jobe stated; our partnerships remain on-going and strong with this and other activities.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com