The U.S. Air Force recently handed contracts to five different companies, each one with a maximum value close to $1 billion, for work related to the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion program, or NGAP. This engine is expected to at least power the sixth-generation manned stealth fighter-like jet now being developed as part of the larger Next Generation Air Dominance effort, or NGAD. That Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman were among the NGAP contract recipients shows that the Air Force is opening the field to new potential engine suppliers and underscores the ongoing competition around the overall design of the next-generation manned aircraft that these engines are expected to power.

The Air Force Life Cycle Management Center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio awarded the NGAP contracts on August 19, according to the Pentagon’s daily contracting announcement. Each one of these awards was valued at $975 million. In addition to Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman, General Electric and Pratt & Whitney also received NGAP contracts.

The core details of all five contracts were described in an essentially identical manner in the Pentagon notice, with each one stating in part the following:

“[The contractor] has been awarded an indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract with a program ceiling of $975,000,000 for technology maturation and risk reduction activities through design, analysis, rig testing, prototype engine testing, and weapon system integration. The contract is for the execution of the prototype phase of the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion program and is focused on delivering capability enabling propulsion systems for future air dominance platforms and digitally transforming the propulsion industrial base. Work … is expected to be complete by July 11, 2032.

None of the NGAP entries in the Pentagon notice mention NGAD or work on an actual aircraft. However, only General Electric and Pratt & Whitney are currently fighter jet engine makers. They also happen to be the two principal suppliers of engines for U.S. military combat jets.

The awarding of contracts to Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman is therefore interesting on a number of levels. Not least of which is the fact that the Air Force looks to be exploring the potential benefits of direct competition over engines between these companies, which are very likely competing over the manned combat jet airframe component of NGAD, and General Electric and Pratt & Whitney.

In June, Air Force Secretary Kendall disclosed that “we still have competition” with regards to the development of the manned NGAD aircraft, but did not elaborate. At that time, Kendall also said he expected the project to proceed through a very traditional development and acquisition process. Those comments followed an announcement earlier that month that this portion of manned combat jet portion of NGAD had entered the engineering, manufacturing, and development (EMD) phase. In aerospace, among other industries, EMD is generally considered to be the formal start of the development of a particular system.

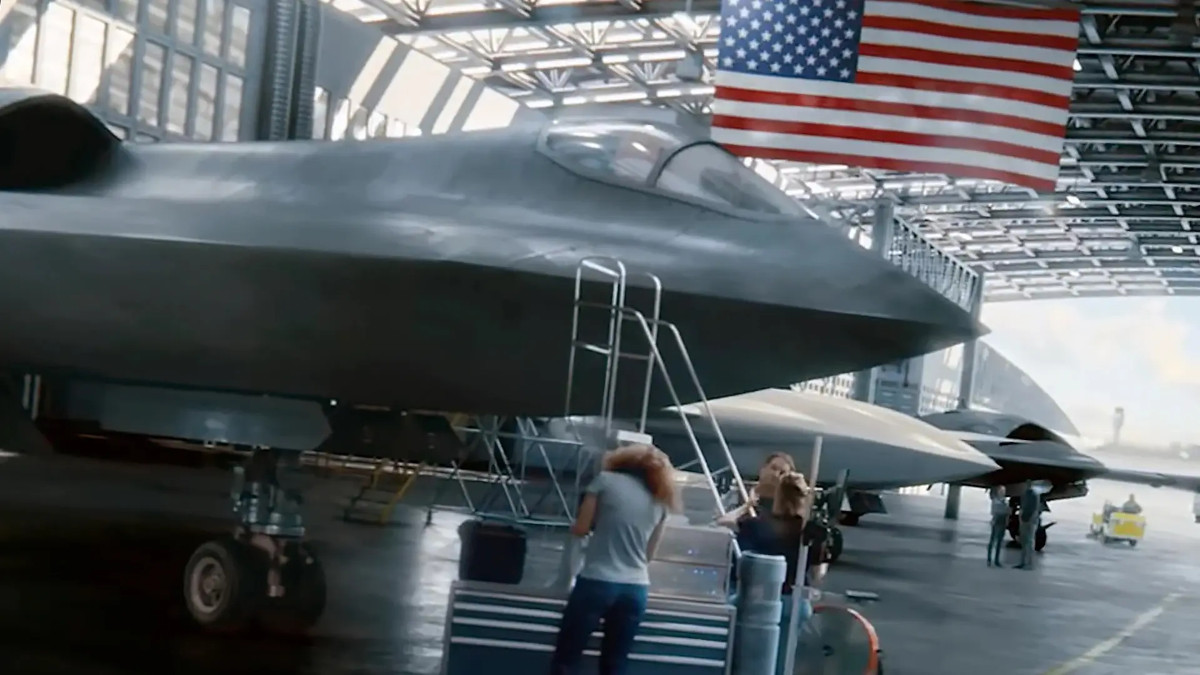

NGAP is also part of NGAD, which consists of a host of different projects seeking to develop various next-generation tactical air combat capabilities, including new weapons, sensors, networking, and battle management capabilities, as well as manned and unmanned aircraft. Though often described as a fighter jet, the planned sixth-generation manned jet will be unlike previous fighter designs. By all indications, the design will put a premium on stealth, range, and payload together over extreme manuverability.

Specific details on the proposed NGAP engines, or the aircraft that they might go into in the future, details remain extremely limited. The entire NGAD program is also highly classified.

The Air Force has disclosed in the past that there is a direct link between the Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) and NGAP. General Electric and Pratt & Whitney each developed advanced engines under AETP, known as the XA100 and XA101, respectively. Though the designs differ in the specifics, both engines feature a ‘third stream’ of airflow that can be dynamically toggled between modes intended for greater fuel efficiency or performance, depending on the situation. You can read more about AETP, and the XA100 and XA101 designs, here.

The immediate focus of AETP was to develop potential new engines for variants of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. On that front, as it stands now, General Electric is advocating for re-engining F-35s with its XA100s, or variants or derivatives thereof. The company has said that the XA100 would increase the range of the F-35A and C variants by as much as 30 percent, as well as offer boosts in acceleration and fuel economy of around between 20 and 40 percent and 25 percent, respectively. All of this, of course, would dependent on specific load-outs, mission profile, and other factors.

Pratt & Whitney is currently proposing a less intensive upgrade of the F135 engines found on all existing and in-production Joint Strike Fighters rather than pushing its XA101. Pratt & Whitney also manufactures the F135.

Secretary of the Air Force Kendall has publicly come out in support of the full replacement option, though he has stressed that this is his personal opinion. The F-35 Joint Program Office is still studying the options, and cost and compatibility issues will likely be major factors. Most significantly, neither of the AETP engine designs, at least as they exist now, will physically fit inside the short take-off and vertical-landing capable F-35B variant. B versions have much more stringent design constraints when it comes to their internal configuration owning to their large vertical lift fans and articulating engine exhaust nozzles, which any new engine would also need to be integrated with.

At the same time, the Air Force has also been warning about potentially serious negative impacts on America’s jet engine industrial base if neither of the AETP options are pursued.

“A portion of the industrial base would begin to collapse,” John Sneden, who runs AFLCMC’s Propulsion Directorate, told reporters at a press briefing earlier this month, according to Defense News. “If we end up with one vendor there, if we don’t move forward with AETP, that vendor can actually get us into a place where we have, essentially, a reduced advanced propulsion industrial base.”

“We need a decision, which is where I am right now,” Secretary Kendall had separately told a gathering at the Potomac Officers Club in July when asked about AETP, according to Air Force Magazine. “I don’t want to limp along, spending R&D [research and development] money on a program we either can’t afford or that we’re just not going to get agreement on among the different services.”

With all this in mind, its not surprising that the Air Force is interested in broadening its potential field of engine suppliers and is seeking to promote competition between the expanded array of companies. This doesn’t rule out the potential for various degrees of interplay between NGAP contract awardees, or others, when it comes to that program, as well as the Air Force’s future sixth-generation ‘fighter’ and other elements of the NGAD program.

While Air Force Secretary Kendall has talked on multiple occasions in recent months about wanting to get away from development cycles with high risks of never producing any tangible and move back to more traditional acquisition programs, he has also left open the door to more novel approaches within that context. Just asking new companies to propose engine options for NGAP, and seriously explore supply chain and other considerations that go along with that, could lay the groundwork that might have longer-term benefits for the U.S. jet engine industrial base.

No matter what, when it comes to NGAP, as well as the aircraft those engines go into, a winner-take-all outcome is highly unlikely. Some of the research and development work that the ‘losing’ companies do on either of these projects could very well still get folded into the final designs as part of a larger team effort. Doing so could help speed up engineering and acquisition processes, as well as spread out cost and risk burdens. General Electric and Pratt & Whitney would be in excellent positions to provide critical production capacity even if their designs don’t win, too.

On those latter points, funding the development of AETP engine variants or derivatives, for any company, as part of NGAD would simply provide an additional hedge against whatever course of action regarding F-35 re-engining that the Air Force, as well as the Marine Corps or the Navy, ultimately pursue. At least in the past, it has been understood that a decision about whether or not to move forward with AETP for the Joint Strike Fighter is expected to come no later than 2024. That is also when the Air Force has been expected to down-select to a single design for the manned component of NGAD.

Differing plans suggest that, if the AETP course of action is chosen, that at least some F-35s could begin receiving the engines between 2027 and 2030. This would be well in line with the expectation, as stated in the Pentagon contracting notice, that the initial phase of NGAP work would be completed by 2032.

All told, it very much remains to be seen what will come of the NGAP effort, and the broader competition surrounding the manned component of the NGAD program. How the AETP decision with regards to the F-35 might impact any of this is still an open question, as well. The Air Force has talked in the past about the possibility of variants or derivatives of an AETP design finding their way onto older fourth-generation fighters, too.

What is clear is that there is a very active competition with regards to the NGAD ‘fighter’ project, including over its engine. The NGAP contracts separately show there is a definite potential to more significantly disrupt the status quo when it comes to powering those jets, as well as others.

All told, the Air Force continues to steadily lay the groundwork for getting whatever design it ultimately chooses as its next-generation combat jet into service in the 2030s.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com