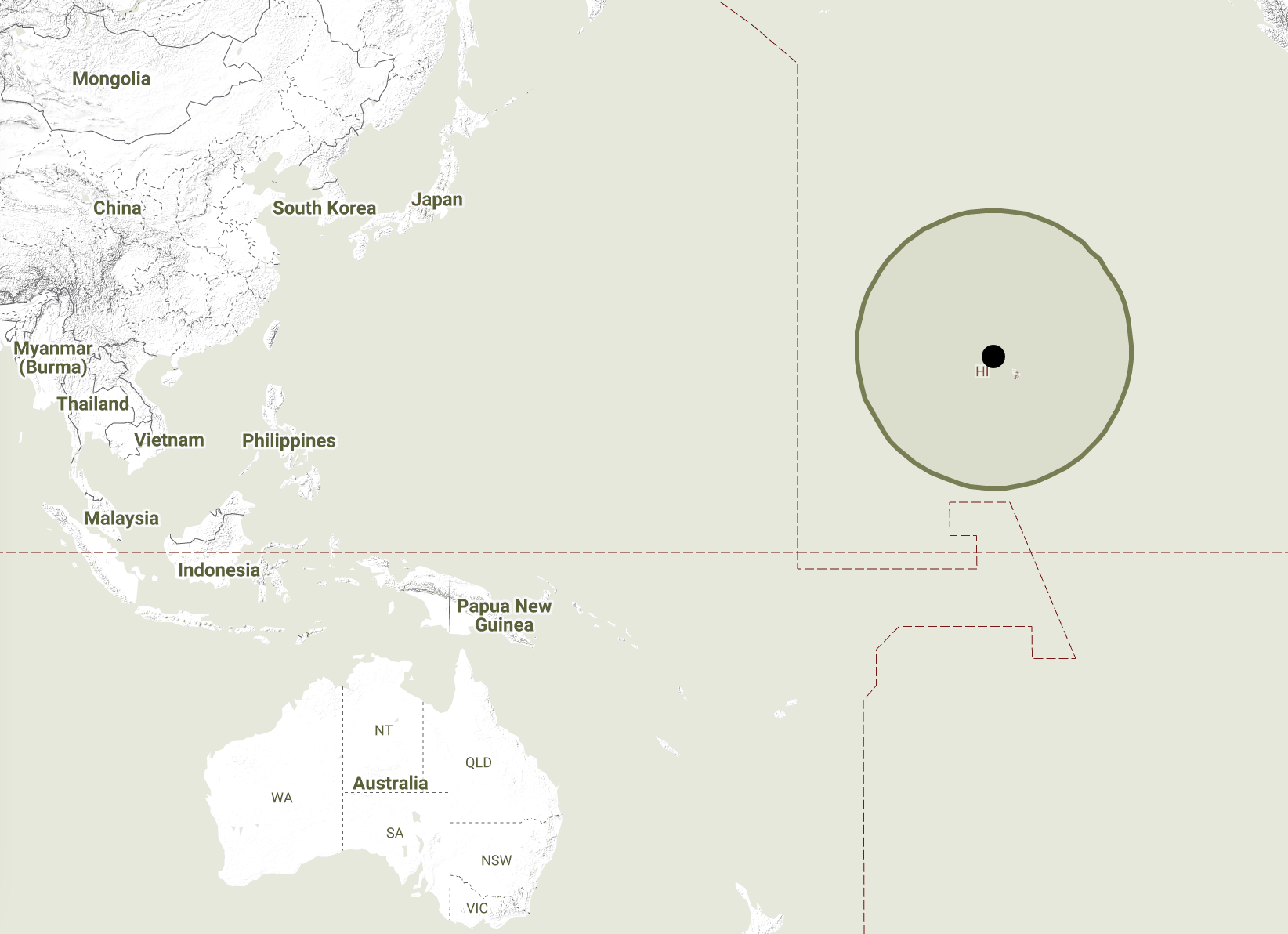

Even with three stops along the way, it takes at least seven aerial refuelings to deploy an MV-22B Osprey nearly 5,000 miles from Hawaii to the Philippines, underscoring the difficulty of projecting forces across the world’s largest ocean. Such trans-Pacific trips are becoming regular for U.S. Marine Corps squadrons as the service responds to aggressive Chinese actions and territorial expansion by boosting its presence in the region.

Four of the Bell-Boeing-built tiltrotors belonging to Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 363 (VMM-363), stationed at Marine Corps Base Hawaii, recently made the 4,730-nautical-mile jaunt to participate in the annual Balikatan exercise hosted by the Philippines armed forces.

From Hickam Field in Hawaii, the Ospreys flew 1,998 nautical miles to Wake Island with three refuelings by KC-130Js flown by Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 152 of 1st Marine Air Wing (1st MAW). That’s almost 2.5 times the MV-22’s operational range, which Bell places at 860 nautical miles at maximum visual flight rules range at long-range cruise speed with all passenger seats occupied. A second leg saw them fly from Wake Island, 1,296 nm to Guam. The third and final leg was from Guam to Subic Bay in the Philippines, another 1,438 nautical miles, according to Marine Corps Capt. Karen Jensen, a spokesperson for 1st MAW. The final two legs required two refuelings each.

VMM-363’s recent trip to the Philippines was not the longest self-deployment Marine Corps Ospreys have made in the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) area of responsibility (AOR). In 2018, eight MV-22 Ospreys from Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 268 completed a trans-Pacific flight from Darwin to Marine Corps Base Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. It was the second time in 18 months that VMM-268 made that 5,300-nautical-mile flight, but involved double the number of aircraft than the 2017 transit. We do not have figures for how many stops and refuelings it took for Ospreys to make the longer transit.

However, the recent trip to the Philippines still showed how much help the aircraft and crews need to project across a region that reaches from the U.S. West Coast to the eastern border of India, from Mongolia to Antarctica, and everything in between.

“This movement has significant strategic value in demonstrating VMM-363’s ability to self-deploy across the INDOPACOM AOR and reaffirms the capability and operational reach that the MV-22 Osprey brings to the nation’s naval expeditionary force-in-readiness,” said Lt. Col. Joe Whitefield, commanding officer of VMM-363.“ Long-range movements of this nature validate the operational mobility of the squadron in support of joint, naval, and Marine Corps operating concepts as outlined in Force Design 2030.”

In 2019, the same squadron completed a different trans-Pacific flight from Okinawa, Japan, to Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, after that year’s edition of Balikatan. That route is now a “recurring milestone flight” for 1st MAW and VMM-268, the Marines said in a statement. VMM-268 recently arrived with its MV-22s in Darwin for the 2022 Marine Rotational Force Deployment, but those aircraft traveled to Australia on cargo ships rather than self-deploying.

The Pacific is almost unimaginably vast. Hawaii-based tiltrotors, ships and helicopters are already 2,500 miles from San Diego. Darwin is 3,375 miles from Tokyo and 4,500 miles from New Delhi. Aircraft capable of self-deploying — flying to forward air bases under their own power — are potent force projection tools though the Osprey’s range is still limited. With a one-way range of just 325 nautical miles, the UH-1Y must be ferried to U.S. bases in the Pacific by other aircraft. An AH-1Z can fly just 310 nautical miles, one-way, and neither H-1 variant can take on gas from a tanker in flight.

Self-deploying rotorcraft across an ocean also requires a vast basing infrastructure, for surface ships and support aircraft, to achieve. In peacetime, the V-22 regularly carries enough fuel to divert a flight to predetermined safe landings zones and therefore could make the trips with less refueling than they might need during a conflict.

They still need bases from which tankers can launch, and ships, and/or island bases to deploy to. The U.S. has been looking for opportunities to expand its Pacific basing infrastructure to help with this, but there is always a risk that remote facilities could be captured or rendered inoperable during a conflict with China. The military also is planning for the future by encouraging, and investing, in development of speedier VTOL aircraft with longer legs that are capable of jet speeds, but they are years in the future.

Not only do the grueling, thousand-mile-plus hops test the endurance of each MV-22, but they also measure the mettle of individual Marine crewmembers and the Corps’ larger logistical and technological capabilities in the Pacific. Assuming the Osprey’s maximum cruise speed of 266 knots — about 300 miles per hour — the VMM-363 crews would have spent about 8.5 hours on the first leg of the most-recent crossing from Hawaii to Wake Island. With a service ceiling of 25,000 feet, the aircraft also would have to dodge inclement weather where encountered, which would lengthen the trip between stops and perhaps require another refueling to reach the intended destination. Lacking a pressurized fuselage, everyone aboard would have to be breathing supplemental oxygen full-time above 10,000 feet. For these and other reasons, each ferry flight requires extensive planning, flawless execution, coordination for aerial refueling, and maintaining continuous satellite communication, the Marine Corps says.

All of this is in the service of the service returning to its sea roots after decades of combat on land in Afghanistan and Iraq. For aviation units, that means flying and fighting as a cohesive Marine Air Group, which has not happened since the initial invasion of Iraq in 2003. A recent deployment of 20 F-35Bs aboard the Navy big-deck amphibious ship USS Tripoli in the Pacific is another example of the Corps exercising atrophied operational skills.

The service is leaning heavily on adopting a concept of operations called expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO), using mobile, sustainable naval forces from temporary locations either on or near land, quickly to conduct sea denial, support sea control, or enable fleet sustainment, according to the Marine Corps. Marines also are practicing fast-roping from the back of V-22s while underway aboard Navy warships in the Pacific, among other amphibious operations-related skills necessary for combat and humanitarian missions there.

“The forward posture and advanced level of readiness gained through long-range training means that 1st MAW can establish expeditionary advanced bases at the time and place of its choosing in support of larger naval campaigns,” VMM-363 said in a statement.

Deploying annually to exercises like Balikatan is a good example of that concept. About 5,100 U.S. military personnel joined 3,800 troops from the Philippines armed forces during the 12-day exercise. Balikatan emphasizes maritime security, amphibious operations, live-fire training, urban operations, aviation operations, counterterrorism, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief, all missions the Marine Corps has been trending toward for several years after being weighed down with heavy equipment and land-based responsibilities in U.S. wars.

Current Commandant Gen. David Berger has launched — and is under heavy fire for — an ambitious plan to reorient the Corps to its roots as the U.S. military’s naval expeditionary force in readiness. Berger has overseen the rollout of Force Design 2030, which calls for the divestment of heavy equipment like tanks and shorter-range aircraft like the AH-1Z Viper and UH-1Y Venom that are outpaced and outranged by the V-22.

The Marine Corps’ primary argument for shuttering its conventional helicopter units in Hawaii is that the MV-22B’s speed and range, together with aerial refueling support from KC-130Js, which are now set to become organic to MAG-24, make the tilt-rotors better suited to operations across the broad expanses of the Pacific.

Part of the ongoing “naval integration” and reorganization plan began in 2021 with a process to deactivate all units operating conventional helicopters in Hawaii. Aside from the still-relatively young AH-1Z and UH-1Y helicopters, plans are to end the operation of CH-53E Super Stallions at Kaneohe Bay, as well. A total of 35 helicopters will cease to operate at the base by the end of fiscal year 2022, which runs through Sept. 30.

That means the inactivation of Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 367 (HMLA-367) and Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 463 (HMH-463), Marine Captain Colin Kennard, a spokesperson for 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force (3rd MEF), told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser newspaper. HMLA-367 and HMH-463 were assigned to Marine Aircraft Group 24 (MAG-24), which belongs to 1st MAW. MAG-24 also has two squadrons flying MV-22Bs, as well as one operating RQ-21 Blackjack drones.

Expect the Navy and Marine Corps to ramp up their presence in the Pacific as the U.S. and its allies seek to counter Chinese expansion in the region. The War Zone will follow along as Marines regain their sea legs and stretch their wings in anticipation of that struggle.

Contact the author: Dan@thewarzone.com