It is cold. It is remote. But with 54 F-35A Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters at a location that is closer to Tokyo than it is to Honolulu, and with easy access to a 77,000-square-mile training range, Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska is one of the U.S. military’s most strategically important installations.

And, with ongoing concerns about threats from China and Russia, integrating the last of those F-35As into base operations, and the Red Flag Alaska 22-3 large force training exercise about to wrap up, it is also at the moment one of the busiest.

“We’ve had quite a bit of action going on here,” said Air Force Col. David “Ajax” Berkland, commander of the 354th Fighter Wing, speaking during an Air & Space Forces Association virtual conversation Wednesday about the bed-down of the F-35As at the base.

The first pair of Lockheed Martin’s stealth fighters arrived at Eielson on Apr. 21, 2020, and was significant on many levels. This remote installation is located 26 miles southeast of Fairbanks in the interior of Alaska and about 110 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

In a wide-ranging discussion about the significance of current base operations, Berkland and Lt. Col. Ryan “VooDoo” Worrell, commander of the 356th Fighter Squadron at Eielson, talked about everything from working on new ways to counter Chinese air defenses to the differences between flying the F-16 and F-35 to what it is like to fly when you have to layer up against the cold.

Together with the F-22 Raptors based at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER), near Anchorage, the arrival of the last of the F-35s at Eielson in April, Berkland noted, gives Alaska “the largest concentration of fifth-gen, combat-coded airpower in the world.”

It was one thing to get the full complement of 54 low-observable (stealthy) fighters in one place. But now it is time to shift gears, Berkland said.

“Our priority now is to basically shift ourselves into full operational capability to be able to do agile combat employment (ACE) operations throughout the Pacific [area of operations] at austere locations,” Berkland said. “So that for us that means that we need to be able to run hub-and-spoke operations with our full complement of fifth-gen combat airpower.”

He is referring to being able to deploy the F-35s, which at Eielson are tasked with supporting U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), “rapidly to the AOR,” or area of responsibility, including austere locations with minimal logistics in place.

“We can really, in a single fighter sortie, range to just about any AOR in the Northern Hemisphere pretty easily,” he said.

All while still conducting advanced training at Eielson and continuing to bed-down rotational forces that come to Alaska.

Home On The Range

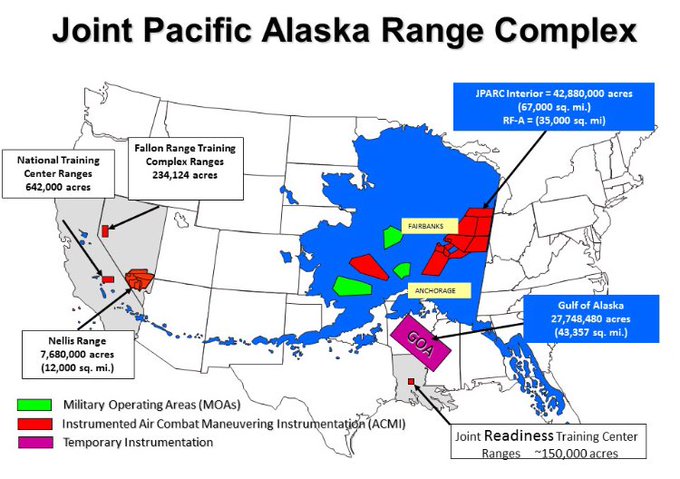

One of the things that make Eielson so important is its proximity to the Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex (JPARC), a grouping of large swathes of restricted airspace that provides a realistic training environment and allows commanders to train for full spectrum engagements, ranging from individual skills to complex, large-scale joint engagements.

“You don’t have to ask me,” said Berkland, about the value of JPARC. “You can ask any of these Red Flag Alaska participants what they think of the JPARC and they’ll tell you this – the best training airspace in the world.”

A Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) -sponsored exercise, Red Flag Alaska 22-3 “is designed to provide realistic training in a simulated combat environment,” according to a PACAF release. “A series of command-directed field training exercises will provide joint offensive counter-air, interdiction, close air support and large force employment training.”

Red Flag Alaska “is a joint international major flying exercise where we take in various squadrons from all domains of warfare from all over the world and we build a scenario where they have to integrate and fight as a team,” said Lt. Col. James Collins, 353rd Combat Training Squadron commander.

Some 2,200 service members flew, maintained and supported more than 115 aircraft from 25 units during this iteration of the exercise. Among them were several U.S. Air Force and Navy units as well as Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and Army troops “training together to exchange tactics, techniques and procedures while enhancing the combat readiness of all participating forces.”

“In this iteration, it’s the first time we’ve had Marine Corps F-35s working with the RAAF’s E-7, while also integrating with Eielson Air Force Base’s own F-35s in addition to Kunsan and Kadena’s F-16s, Navy Growlers and RAAF Super Hornets,” said Collins. “Learning how to integrate with our allies and partners is one of the great things about this exercise.”

But even with everything going on at JPARC, there is an effort underway to make that range even better, Berkland said.

“We’re actively engaged to try to upgrade the JPARC to expand it vertically and horizontally in coordination with our partners here in Alaska, as well as upgrading to the threat replication capability on the surface as well as the air,” he said. “So that’s kind of what’s been going on here.”

The importance of JPARC is underscored by an overall concern for the need to have large areas of airspace to train fifth-generation fighters.

In July, for instance, The 414th Combat Training Squadron and the Federal Aviation Administration collaborated to expand the available training area during exercise Red Flag at Nellis by almost three times the size as prior iterations.

“This is the first Red Flag exercise featuring dedicated fifth-generation aggressors, who are using longer-range offensive and defensive measures to provide exercise participants more realistic threat replication,” the Air Force said in a release at the time. “The expansion of the airspace has allowed for training to more closely align with the National Defense Strategy’s focus on the pacing challenge.”

JPARC is more than twice the size of even the expanded training area that was used during the latest iteration of Red Flag out of Nellis AFB, a volume of air space well appreciated at Eielson.

“The biggest thing that we’re starting to see as both squadrons are fully fleshed out, we have the capacity to run full exercises with 48 F-35s,” said Worrell, who runs one of Eielson’s two F-35 squadrons. The other is the 356th Fighter Squadron.

“We can easily integrate with the Raptors down from the south. So we do integration on a quarterly basis with the Raptors on the JPARC…I mean, we call the bros down the street and …we can train with a single sortie, so that’s a big advantage of being here in Alaska.”

The F-35s at Eielson and the F-22s at JBER train every day at JPARC with the 18th Aggressor Squadron, also based at Eielson.

“JPARC is the size of the state of Indiana,” Berkland said. “If anyone on the line is from Texas, I apologize upfront, but if you were to cut Alaska in half and make it into two states, Texas would be then the third biggest state after the two Alaskas.”

The vast expanse of JPARC, combined with the capabilities of the F-35, makes for an excellent place to train against potential Chinese air defense threats, Berkland said.

“When you look at what the advanced threats are, they’re becoming more lethal and they’re becoming more lethal at further and further ranges in terms of the ability of an air defense system to detect, target, and then engage our joint forces,” he said. “So having a range like the JPARC and having all the different assets between us and the 3rd Wing down at Elmendorf, enables us to train for the high-end fight and it enables us to have the space to innovate tactics, techniques and procedures to survive and be lethal in that advanced threat environment. We’re definitely watching very closely all the developments across the globe that our competitors are pursuing and we are training to that every day.”

In training to those advanced threats, Worrell said that “we found that stealth is not necessarily the ultimate answer, but it is an entry-level requirement. If you’re not bringing your A-game from the beginning, you don’t have additional flexibility to continue to do those things because the threats are continuing to spread on the electromagnetic spectrum.”

The threats, he said, are “not staying in the X Band. They’re spreading out across the whole EMS [electromagnetic spectrum] and that still enables us to decide and determine ways to defeat that … and bringing the whole force to bear is another big piece of what we are continuing to work on in the JPARC.”

No longer is training limited to just a four-ship flight of F-35s, Worrell said.

“It is a four-ship of F-35s. It is four Raptors. It is three [EA-18] Growlers. It is integrating our Australian partners up here with the [Boeing E-7] Wedgetail and bringing in all the other non-kinetic effects that we can during those Red Flags…and understand the capacity of where that is going to be an enabler in the fight.”

The Red Flag Alaska 22-3 exercise, which wraps up on August 12, highlighted one potential vulnerability, Berkland said.

“We integrate all domains into our Red Flag Alaska exercises,” he said. But space is “something that we’re working on ramping up, to be quite honest, because that is the domain that is ever more important and potentially a vulnerability that we need to shore up and again Red Flag Alaska is the perfect place to do that.”

F-16 Versus F-35

“The F-16 is still a great platform and a great asset that we get to use and need in the Air Force,” said Worrell. He used an automotive analogy to compare the two.

“So you could have an awesome ‘69 Mustang that is a blast to drive. It goes fast. Makes a lot of great noise. It still does the job extremely well. But then you can compare that to a Tesla, which is a newer, modernized, more computer-based system and some of the things you’re doing are less about driving the car and more about managing the decisions that you’re making.”

The F-35, he said, “brings a lot more sensor [situational awareness] and a lot more automation into how the sensors provide information to the pilot so that I’m no longer running the radar. I’m no longer trying to manage where my radar is looking to get the correct aspect on something. There’s still some pieces to that, but it’s much more about what decisions the pilot making in the cockpit now. That has changed how we started to train our four-ships and our wingmen.”

Another major difference between the F-16 and the fifth-generation F-22s and F-35s is the ability to work together while being much further apart.

Instead of having a wingman who is a mile away, “he’s now five to 20 miles away,” said Worrell. “He needs to be in position, making the same decision for what the four-ship is intending to do. And the jet really enables that from a sensors perspective and the awareness that he has around the battlespace.”

Berkland said that when he came over to the F-35 program after flying F-16s out of Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, he thought it would be an easy transition.

“Honestly, I kind of scoffed at it and I thought, ‘hey, this will be easy,’” he said. “It’s a Lockheed jet. Single-engine. Side-stick. Got some buttons and switches on the throttle. And eventually, it’ll be easy. “

But Berkland said that what he didn’t fully grasp, “was the fundamentals of what makes a fifth-gen airplane, a fifth generation. And those would be two things – stealth and the sensor fusion that VooDoo talked about.”

Though the F-16 “is the love of my life,” Berkland said that it “simply can’t go places that the F-35 can go” because it does not have the same advanced sensor capabilities.

“So when you look at different AORs and the anti-access area denial capability that certain adversaries are fine-tuning, the F-16s can’t get into some of those places. The systems the F-35s are using …enables a degree of situational awareness that you just really, really struggled to get in a fourth gen platform.”

Dogfight Dilemma

While the F-35 was not renowned as a “dogfighter” it does have advantages in air-to-air combat, Berkland said.

“It comes down to the pilot and having the awareness of exploiting your advantages while taking advantage of what the bandit is doing, and may be doing,” he said. “It’s a very capable platform from that perspective and very fun to fly.”

One advantage, he said, is the ability of the F-35 to have a high angle of attack – the angle at which the chord of an aircraft’s wing meets the relative wind.

“Coming from the F-16, just to talk strictly pilot terms, the angle of attack (AOA) capability of the F-35 is pretty cool. The ability to pull lots of AOA and put your nose on something, whereas in the F-16, you weren’t necessarily able to do that because of the AOA limitations on it, so that’s a cool capability.”

Another advantage is the engine.

“The engine is great,” said Berkland. “At least in terms of thrust, it’s got a lot of thrust. You can go very quickly. Certainly to Mach [Mach 1] you’ll get there probably faster than anybody. And then once you get the Mach, you know, the F-22 will probably pass you by and keep going. But it’s a great airplane that works very well out here on the JPARC, I can tell you from flying at low levels, as well as doing a lot of high-altitude stuff. Across the board, it performs great.”

Frigid Flying

Before setting foot in the cockpit, F-35 pilots at Eielson have to layer up, Worrell said.

First pilots don fleeces. Then a flight suit. Then the G-suit. Then a snow jacket. And then the Joint Strike Fighter Jacket. And then minus-50-degree-rated boots.

“Then at that point, you’re so hot, you just want to get out of the building,” Worrell said, adding that pilots prefer to walk out to the planes in temperatures dipping to 30 or 40 degrees below zero rather than drive there just to keep from overheating.

“Then you get in a jet, and the goal is just not to sweat until you get out there and flying,” he said. “So that’s just an extra challenge of flying up here in Alaska.”

But given the conditions in and around Eielson, there’s good reason to bundle up. And it’s a key reason that before pilots in Alaska even get to that point, they have to go through Arctic training school, conducted at Eielson.

It’s “fantastic training,” he said. “Very sobering. Or chilling, maybe, would be the right word, because you’re out there for a couple of nights and surviving. It’s minus 50. And all you have is your life raft, your single-person life raft, and then you build some kind of shelter over that. And then the second night, you actually build a ‘no-kidding’ shelter that you cover up with snow and you don’t sleep, you survive. That is the goal.”

And it’s like “a lot of innovation,” he said.

“So for example, the F-35 seat kit doesn’t fit the sleeping bag the F-16s could fit, which is a nice warm sleeping bag. You could actually get some sleep in that thing. But we had to be innovative and come up with something that would fit in the F-35 seat kit that would allow you to survive, if not be comfortable.”

That resulted in what Berkland described as “almost like a full-body poncho kind of design. It’s very thin. But it does keep you warm enough to actually survive that critical 12 hours that we assess we need in order to get that HH-60 with [combat rescue officers] and [pararescue jumpers] out there to pick us up on the range.”

Keep Them Flying

Berkland said that while he didn’t know what the Eielson’s F-35 mission capable rate is at the moment, “I can tell you that it is significantly better than anything I’ve ever seen before.”

Maintenance at the base “outperforms our expectations. On a daily basis, ops has a tough time keeping up with maintenance here.”

The number of planes he can put in the air on any given day “comes down to pilot availability…So that has been fantastic. Some of that is the fact that we have very new airplanes. But I think a lot of it has to do with the amazing team that we have up here that takes pride in doing all those things.”

That’s especially important in the frigid climate of Eielson.

“We have a motto that we’re ready to go at 50 below,” he said. “It does get to that temperature at certain times of the year. But our team has a sense of discipline. Because, frankly, there are no shortcuts. If you don’t follow the tech order, if you don’t do all the little things, if you delay maintenance actions, you’re going to pay for it when it’s 50 below and dark out all day long.”

While the aircraft itself has proven to be reliable even in the extreme cold, Berkland said he is concerned about keeping the F-35s, which require a lot of parts to keep flying, sustained especially over long distances.

“One of the challenges that we are working on is reliability when conducting disconnected operations when you’re not necessarily connected to ALIS,” he said, referring to the Autonomic Logistics Information System, the F-35’s supposedly universally available health and maintenance data system. “It’s not been a mission stop, but anything that we can get from industry, certainly from Lockheed Martin, to help us navigate that, that’s what we are really looking to do in the future.”

The Pentagon has been working toward a replacement for ALIS, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter’s long-troubled cloud-based computer brain. The U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy have said that the existing system is one of, if not the most significant factor in the abysmal mission capable rates for their respective F-35 variants and a major contributor to the growing sustainment costs for the aircraft.

In January, the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO), in partnership with Lockheed Martin, took another step in the transition from ALIS to the modernized F-35 Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN) logistics information system by fielding the first 14 sets of new ODIN hardware to F-35 squadrons, according to a JPO release, which said the move was on schedule, and within budget.

Berkland said a recent situation at Marine Station Iwakuni Japan “shows some of the challenges” of far-flung logistics. “And something we’d like to see refined in the future.”

One of his squadrons needed a part for an F-35. Though the Marines had it at Iwakuni, the squadron had to go back to Lockheed, “and through some degree of bureaucracy to get approval to source that part.”

“If we could get more flexibility in that arrangement so that we can actually source that part more flexibly, I think that would be a game-changer for us.”

Worrell said the other logistics challenge “is how long sometimes it takes to get something to a place if it’s not there. And advocating for the right priority of when it needs to be there. Being in Alaska, we are kind of at the end of the logistics train for most of our parts and supplies.”

Adding to that challenge is a supply chain model where the part is ready at the time of need, not necessarily on hand in stock.

He used the example of the F-35 pilot’s custom-fit helmet to show the fragility of the supply chain and what he is doing to help fix that.

“If I take away a pilot’s helmet, he’s not going to fly” because it’s custom-built to fit the pilot.

So instead of investing in having some extra helmets on hand, that pilot has to wait, grounded, for five or six days for a new helmet.

The consideration becomes how much equipment a squadron brings on an ACE or any other expeditionary event.

“We’re working through tailoring those cargo loads to bring just that we need to sustain the initial operations under the assumption that we’re going to have a follow-on backfill, and we have to then have reliable communications to communicate what we need on that two-week shipment that’s coming in,” said Worrell. “So those are the challenges when it comes to execution.”

Despite logistical and weather challenges, and the increasing threats posed by both China and Russia – exacerbated by melting Arctic ice that is opening trade routes, thus adding to global competition for territory and resources – Eielson Air Force Base and its 54 F-35s will only become more important to the nation’s defense as time goes by.

“So when it comes to us deploying forces throughout the AOR, I don’t want to get into specifics,” Berkland said. But the goal of “dynamic force employment” being conducted out of Eielson “is to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com