When an unflagged vessel smuggling advanced arms to the al-Shabaab jihadi group was spotted in the waters off Somalia last week, there was no time to send a boarding party to interdict it, a U.S. defense official told The War Zone Tuesday morning. So, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) made a rare decision, calling in an airstrike. The ability to do so was, in large measure, made possible by new authorities given to commanders to act, the official told us. This is meant to speed up critical kill chains and increase the effectiveness of the force that has to keep ahead of enemies on a fast-moving modern battlefield. But even with the clear benefits of increased authorities down the chain of command and forward in the field, there can be added risks.

“This was a time-sensitive issue,” said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss operational details. “They have to do things quickly. They did not have time to pull in boats.”

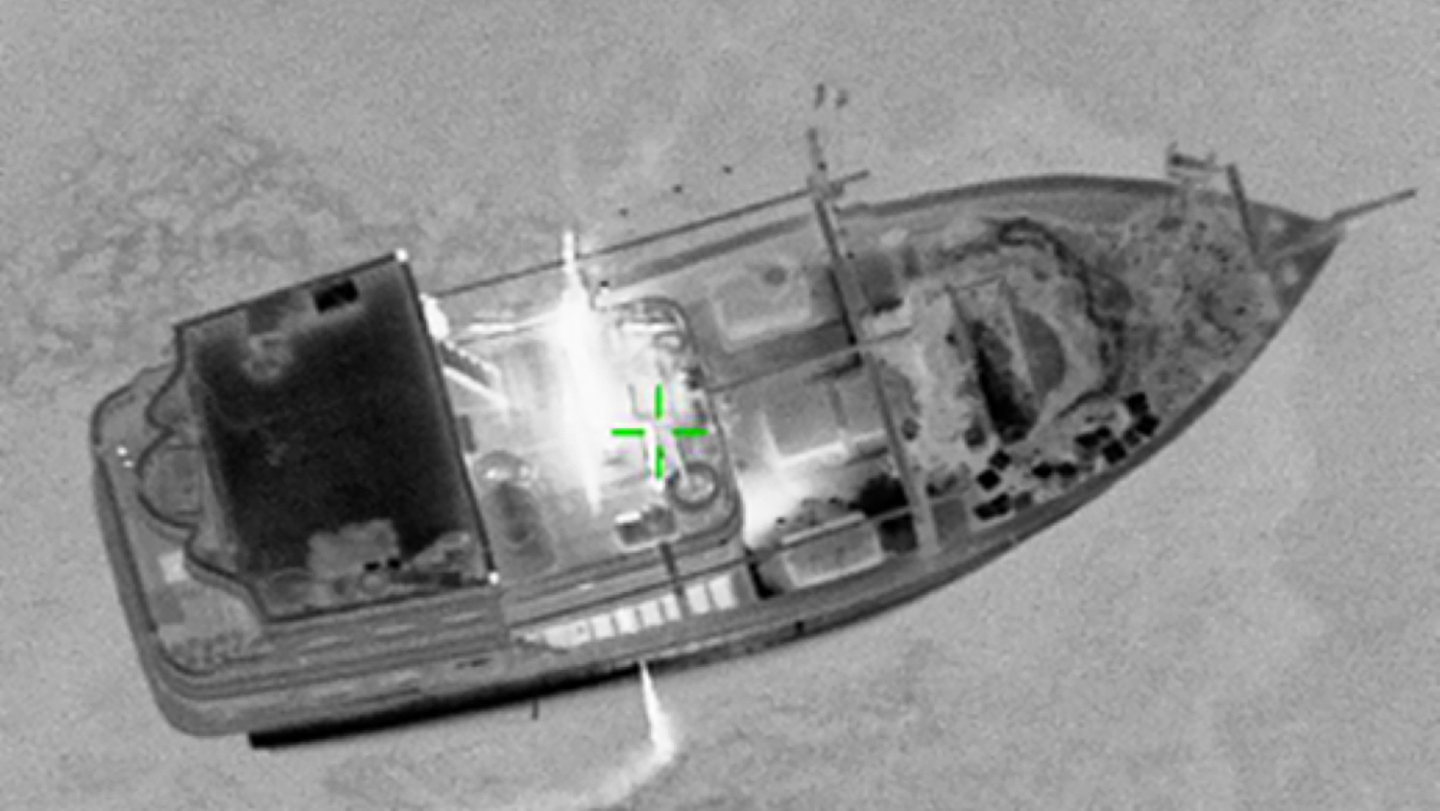

“In coordination with the Federal Government of Somalia, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) conducted airstrikes against advanced conventional weapons aboard a flagless vessel and a smaller supporting vessel inside Somalia territorial waters on April 16, 2025,” the command announced. “The weapons were en route to al Shabaab terrorists inside Somalia and posed an imminent threat to partner and U.S. forces in Somalia. AFRICOM’s initial assessment is that no civilians were harmed.”

Everyone aboard both vessels was “neutralized,” the Somali Ministry of Information added.

AFRICOM declined to say what kinds of weapons were involved, how the strike was carried out or by what branch.

Interdiction of arms at sea is not unusual in this part of Africa and the Middle East. Smuggling everything from AK-47s and ammunition to advanced missile components are regular occurrences around the Horn of Africa and the southern Arabian Peninsula. Illicit arms deals to extremist groups and support for proxies in the form of weaponry has plagued the region for a very long time.

Though routine, these operations remain inherently dangerous, as borne out last year by the deaths of Navy Special Warfare Operator 1st Class Christopher J. Chambers and Navy Special Warfare Operator 2nd Class Nathan Gage Ingram. The two Navy SEALs were attempting to board a vessel in the Arabian Sea carrying Iranian-made ballistic missile and cruise missile components from Iran to the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

When boarding the boat, Chambers slipped into the gap created by high waves between the vessel and the SEALs’ combatant craft, officials said. As he fell, Ingram jumped in to try to save him. Both men perished.

An airstrike against vessels, meanwhile, is practically unheard of. The U.S. official said it has been at least five years, and probably longer, since that last happened, if at all, in the AFRICOM region.

The ability to rapidly carry out attacks like this one is the result of U.S. President Donald Trump and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth giving local commanders more authority to act, the U.S. defense officials told us. That AFRICOM is doing so is the result of increased activity and presence by groups like al-Shabaab and ISIS operating in northern Somalia.

“Commanders have been given more delegated authorities, than under the previous administration, to act and a wider range of targets,” that can be hit, a second U.S. defense official told The War Zone.

These changes are reflected in the drastic increase in airstrikes against al-Shabaab and ISIS targets.

“So far this year, we conducted 20 airstrikes against both ISIS Somalia and al-Shabaab,” the official told us. “We did 10 all of last year.”

The last strike on a ground target came the same day as the vessels were hit. The attack took place near Adan Yabaal, according to AFRICOM.

“Al-Shabaab has proved both its will and capability to attack U.S. forces,” AFRICOM said in a statement at the time. “AFRICOM, alongside the Federal Government of Somalia and Somali Armed Forces, continues to take action to degrade al Shabaab’s ability to plan and conduct attacks that threaten the U.S. homeland, our forces, and our citizens abroad.”

Retired Army Gen. Joseph Votel, former commander of U.S. Central Command, told us the value of having greater authority to act.

“One example of an authority that I asked for and received was the ability to move forces back and forth between Iraq and Syria,” explained Votel, now a Distinguished Military Fellow at the Middle East Institute. “Prior to 2017 – our policy had been strict management of the numbers and capabilities in each country. As the campaign progressed, we needed more flexibility, especially in Syria. Being able to move forces back and forth under my own authority, as opposed to seeking approvals through the National Security Process, gave us the flexibility and agility we needed to finish the campaign. I think the big idea is to get decision-making at the lowest competent level – the commander/leader who has the knowledge of the situation as well as the requisite judgment and experience. This does not always mean the most junior or most senior leader – it is the one who is best enabled to make the decision.”

Conversely, he added that he had to get approval for “certain operations in Yemen.”

While reducing the need to seek permission has its advantages, there are potential downsides. Speeding up the kill chain can introduce higher risks, including misidentification, collateral damage, and unintended geopolitical ramifications. In addition, as in the case of the boat attacked by AFRICOM, the decision to make a swifter strike removed any intelligence value that could have been gained if there had been time to capture it.

The new authorities, which affect airstrikes and commando operations, were implemented in response to a much more restrictive process under Presidents Joe Biden and Barack Obama, CBS News noted in the first story about the easing of the rules.

Under the Obama administration, before launching a drone strike in Somalia or Yemen, “military commanders had to ensure it met a number of strict criteria and obtain approvals from seven decision makers — including the president,” the network explained. “The individual targeted had to be confirmed as a member of an approved terrorist organization using two independent forms of intelligence. Civilian casualties had to be projected as minimal. And there could be no ‘contradictory intelligence’ muddying the waters.”

The Biden administration had similar restrictions.

An official interviewed by CBS “added that Mr. Trump’s approach carries both risks and rewards because the streamlined process can potentially degrade foreign terrorist organizations’ capabilities faster, given the lower threshold required to strike and widened target selection, but it inherently raises the risk of flawed decisions and unintended civilian casualties.”

It is unclear if these new permissions extend beyond AFRICOM.

Earlier this month, AFRICOM’s commander, Marine Corps Gen. Michael E. Langley, testified before Congress that the new authorities have spurred action.

“Al-Shabaab is especially a heightened terrorist threat, namely because they’re colluding with the Houthis across from Yemen,” he stated. “So we’re watching that closely. The president and the Secretary of Defense gave me expanded authorities … I will say, we’re hitting them hard. I have the capability to hit them hard.”

Langley further stated there was good reason to have that additional authority. Groups like al-Shabaab and ISIS, he told senators, are a “direct threat on the homeland, whether it’s just their networks or even their ideology.”

He pointed to the Jan. 1 terror attack in New Orleans, when 42-year-old Shamsud-Din Jabbar, a U.S. citizen from Texas, drove a truck into a crowd of revelers, killing at least 10 and injuring dozens. Jabbar had an ISIS flag in his truck and was motivated by their beliefs.

“This is an event that was inspired by a foreign terrorist ideology,” then-Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas told CNN at the time. “This individual ascribed to the heinous beliefs of ISIS.”

Though AFRICOM has increased the tempo of its attacks, as we previously noted, the Trump administration is looking to pull back from Africa. That includes the possibility of making AFRICOM subordinate to U.S. European Command (EUCOM). Both are currently headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany.

Even if it is subsumed, commanders of AFRICOM or what remains of it, will likely still have a major role in kinetic actions on the continent. The additional authorities provided under Trump and Hegseth should continue to speed up the kill chain if more attacks against these groups are required.

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com