While defense contractors can be shameless in trying to sell their products, they don’t always offer a complete vision of certain aspects of future warfare. But based on a collection of concept art, at the height of the Cold War, Ryan Aeronautical pitched their Vertifan jump jet as the future of air power.

When Ryan’s experimental XV-5A Vertifan made its first flight On May 25, 1964, the California-based plane maker had already been at work on the concept for more than two years. The U.S. Army had only ordered two of the planes, but the firm envisioned the prototypes as the first step to building jump jet fighters for the U.S. Air Force and Navy, interceptors for the West German Luftwaffe, sub hunting patrol planes, and small counter-insurgency aircraft, all of which could take off and land vertically without the need for conventional runways.

By the end of the 1950s, the U.S. military and many of its allies had become interested in the idea of jump jets. Experience in World War II had shown that taking out runways could cripple an enemy’s air force without necessarily having to eliminate production lines or destroy individual aircraft. With the advent of nuclear weapons the United States realized it would be particularly easy for the Soviet Union to take out entire air bases with minimal effort.

This concern was even more pronounced for countries, such as West Germany, which sat right on the border of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies. An aircraft that could take off and land vertically or otherwise operate without the need for large, conspicuous improved runway offered a possible way to keep forces safe and available for a counterattack during a future conflict involving atomic weaponry.

Various countries experimented with vertical take-off aircraft in different configurations. In its actual prototypes, Ryan’s Vertifan design involved separate jet engines and lift fans to achieve level and vertical flight respectively. However, the lift fans were not independently powered. When the pilot switched from level to vertical flight, a cut-off valve redirected the jet exhaust and used it to physically spin the fans.

Not surprisingly, Ryan’s art showcases these prototypes, with twin jet engines and lift fans in the wings and nose, which the company had crafted for the Army. Offering the ability to operate like a helicopter, but with the cruising speed of a fixed wing jet, the service wanted to explore their potential in both the close air support and rescue roles.

But Ryan didn’t expect stop there. Artworks depict a stubbier Vertifan specifically for counter-insurgency operations. The concept looks like a hybrid between the XV-5 and North American Rockwell’s OV-10 Bronco. Based on the art, this version would have involved a turbojet engine driving a pusher propeller in the tail, as well as providing the exhaust to drive the lift fans. In scenes that evoke a Southeast Asian setting—the U.S. military was becoming increasingly embroiled in Vietnam as Ryan continued to refine its prototypes—these aircraft carry rocket pods under their wings while operating from austere camps and attacking insurgent-controlled villages.

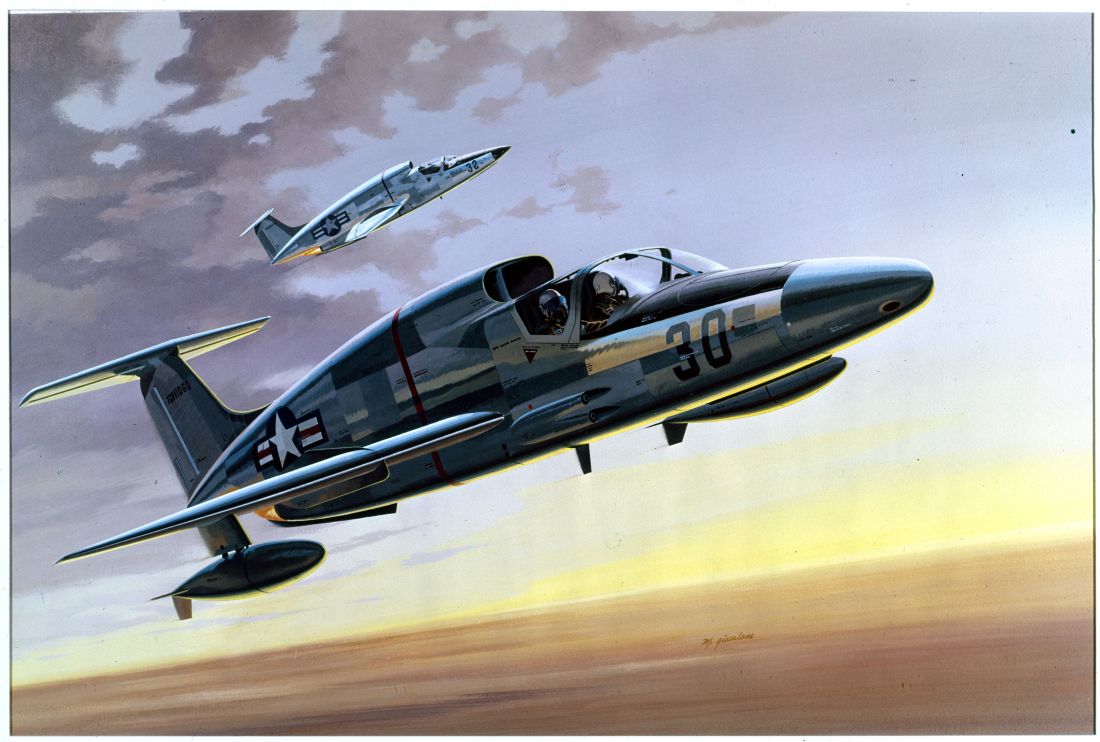

Ryan had options for other services, too. One slide features a pair of potential Air Force fighter jets in a similar configuration to the XV-5. The aircraft in the foreground has two under-wing drop tanks and what appear to be four cannons. At the time, the service was still flying the F-100 Super Sabre fighter, which had a similar armament.

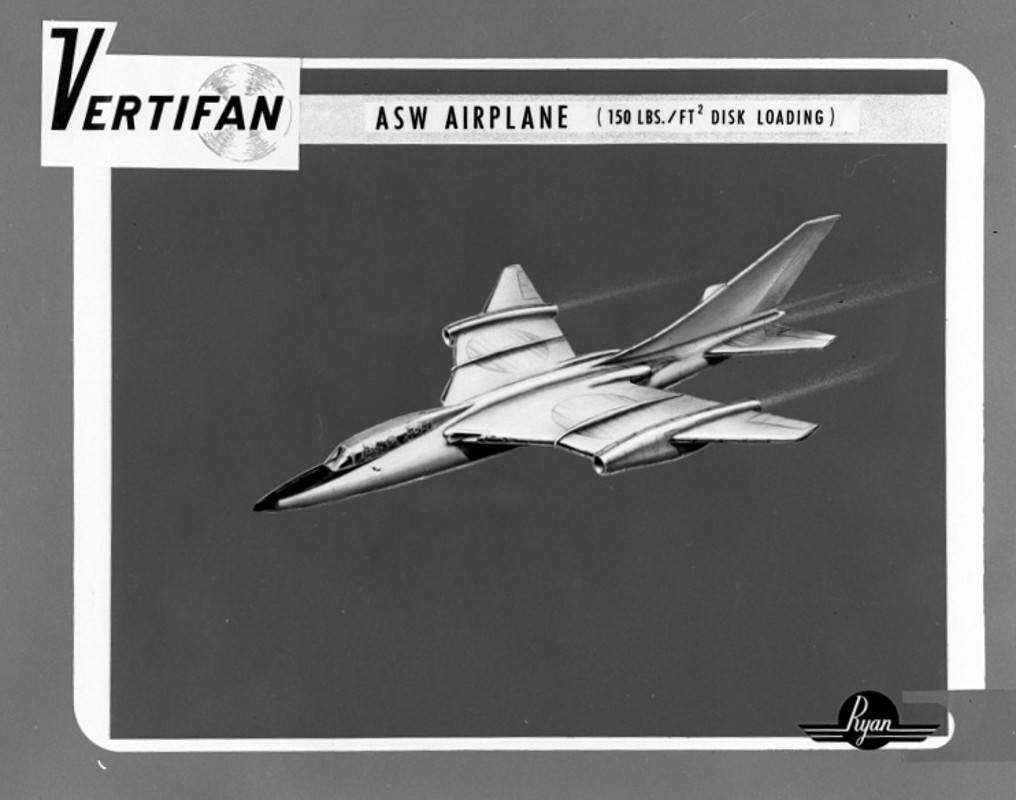

Another image shows an elongated Vertifan design in a Navy paint scheme flying along with A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft and F-4 Phantom fighter jets. One of the A-4s is refueling the Vertifan in mid-air using a “buddy pod” system. It’s not entirely clear whether the proposed variant was a fighter, attack aircraft, spy plane, or electronic warfare platform – akin to the EA-3B and EKA-3B Skywarriors – since it carries no obvious weapons, but has pods or slipper tanks on its wings. There was also a larger anti-submarine warfare concept, which Ryan would likely have pitched to the Navy, too.

Then there’s a painted scene involving three West German Vertifans, all much longer than the XV-5 prototypes, with two sets of fans in the forward and rear fuselages. The port for a forward-firing cannon, such as the M61 Vulcan, is visible and the pointed nose looks perfect for an air intercept radar.

It’s worth noting that at the time, the Luftwaffe was actively exploring zero-length launchers capable of blasting the F-104 interceptor into the air, as well as domestically produced dedicated jump jets such as the EWR VJ 101. German firm VFW continued this work into the 1970s, ultimately developing the experimental VAK 191B. The German military did not put any of these designs into service.

The Vertifan itself ended in failure, suffering from reliability problems and intra-service rivalry. In April 1965, one of the two XV-5As was totally destroyed during a demonstration flight, which killed the pilot. The next year another accident claimed the life of a second test aviator. During an experiment with a rescue hoist system, a manikin representing an injured soldier had gotten caught in one of the lift fans, destabilizing the aircraft.

Ryan rebuilt the prototype with various improvements, leading to the XV-5B. Unfortunately, at the same time, the Army was losing a long-running bureaucratic battle with the Air Force over its right to fly fixed wing aircraft. The Air Force and its supporters ultimately managed to kill off the Army’s Vertifan program.

With no interest in using it themselves, the Air Force effectively doomed the project as a whole. Ryan never found buyers for any variant of the Vertifan. Instead, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps focused on testing the British Hawker Siddeley P.1127, which eventually led to the Marine’s adopting the AV8 Harrier jump jet in 1971.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com