Iran’s fake aircraft carrier – which appears to have sunk and could now a major shipping hazard – certainly captured the most interest during the country’s recent major exercises in and around the strategic Strait of Hormuz. However, the drills also featured what were apparently buried launchers for short-range ballistic missiles, which one top Iranian official referred to as “missile farm.”

In principle, this concept could help reduce the vulnerability of these weapons to pre-emptive strikes while still keeping them in place and ready to launch. It is something the U.S. military actually explored during the end of the Cold War as a way to protect its then state-of-the-art LGM-118A Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), but abandoned the idea for a host of reasons.

Videos from the exercises, dubbed Great Prophet 14, which took place at the end of July 2020, show the launch of at least two separate missiles from buried launchers. Experts and observers noted that one of these appears to be a variant of the Fateh-110, one of Iran’s most prolific short-range ballistic missile families, which reportedly includes variants with radar-seeking anti-radiation seekers and anti-ship capabilities. Iranian officials say the latest missiles in this series have a maximum range of around 186 miles. The other could be a previously unknown type with a similar overall size, but the video quality is low and it could just be another Fateh-110 version.

There was also footage of a tubular containerized launcher firing a missile, possibly one of Iran’s more capable Dezful or Zulfiqar short-range ballistic missiles, from an above-ground position. This system could be intended to be used operationally after being buried, as well. Zulfiqar can reportedly hit targets out to almost 435 miles, while Dezful, a derivative of the former missile, is said to be able to reach targets up to just over 620 miles away.

The footage Iran released of the tubular launcher is seen in the video below in a particular segment that starts at around 1:27 in the runtime.

“Underground ballistic missiles during Great Prophet-14 maneuvers,” Amir Ali Hajizadeh, the head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard’s (IRGC) Aerospace Force, reportedly wrote in a Tweet on July 29, which seems to have been deleted. “The name and description of the missile is a secret. #missile-farm.”

It’s worth noting that “missile farm” has been applied in the past, at least by outside observers, to Iran’s James Bond-esque underground facilities for the construction, maintenance, and launch of larger medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Also sometimes referred to as “missile cities,” these built into mountains and have apertures through which personnel can fire the missiles from safely within. You can read more about these facilities in this previous War Zone story.

In principle, burying launchers in flatter terrain makes sense in many ways. For one, it helps protect the missiles in these areas, where there is much less natural above-ground cover. It also means that shorter-range weapons can be pre-positioned without having to move them to forward locations, and potentially expose them to attack or at the very least giving adversaries an early warning, during a crisis. The Great Prophet 14 exercises also featured short-range ballistic missiles on traditional truck-mounted launchers that would be more vulnerable to detection and then enemy strikes during an actual conflict, as well.

It would only take a relatively limited number of personnel to oversee large sections of any such “missile farm,” with command bunkers being located some distance away from the launch sites. At the same time, this would further increase the number of targets an opponent would have to locate and then engage to neutralize the threat. This concept would offer a much lower-cost method of achieving all this compared to traditional hardened silos, as well.

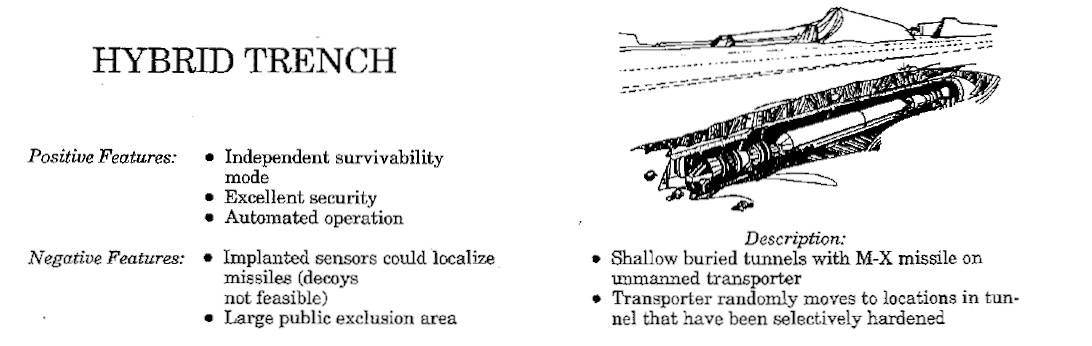

The U.S. military actively considered and actually experimented with doing just this during the development of the MX ICBM, which eventually became the LGM-118A Peacekeeper, during the 1970s and 1980s. Multiple types of buried trenches, including concepts where manned or unmanned launch vehicles would move regularly through them to make it even harder for an opponent to target the missiles, were among the different MX basing options that the U.S. military considered.

If the order ever came, the launchers would break through the top of the trenches to fire their missiles. The video below shows a test using a static launcher to gather data on how such a system would burst up from the ground.

The U.S. military considered a number of other novel basing options for MX. In the end, the U.S. Air Force fielded the LGM-118As in traditional silos starting in 1986. Due to a variety of factors, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, the service retired those missiles completely in 2005.

Many of the negative factors that led the U.S. military to decide against the trench options, as well as certain other alternative silo concepts, for Peacekeeper still apply for Iran 30 years later. Burying the launchers could make inspecting the weapons and servicing them difficult, raising the possibility that they might not function properly when they are needed.

The launchers also still need to be close enough to the surface to be able to effectively fire the missiles, which might limit the amount of actual protection they offer. This was one of the reasons why the U.S. proposals involved mobile launchers in long inter-connected trenches to make it hard for an opponent to ever know for sure where the actual weapon was at any one time – much more significant infrastructure that could have easily been prohibitively expensive.

Even in the 1980s, there were also concerns that sensor technology, or the seekers on incoming weapons themselves, would improve to the point where the buried missiles would still be vulnerable. Commercial space-based imaging satellites are known to be capable of detecting large buried objects and one would imagine that the U.S. government’s capabilities in this regard are even more advanced. It’s hard to see how Iran could bury a large number of missile launchers without that construction activity being visible to American spy satellites, as well. Depending on where Iran might position its “missile farms,” they could be within range of the ever-improving imaging capabilities of manned and unmanned aircraft, as well.

The distributed nature of these fields of buried missiles could still present a complex targeting situation for an opponent who might struggle to neutralize multiple missile farms quickly in the opening phases of a conflict. At the same time, once any missiles are fired, the underground launch sites are fully exposed and there’s no possibility of rapidly relocating the launchers themselves, unlike mobile transporter-erector-launchers. They would certainly not be anywhere near as able to withstand counterstrikes the way the more robust mountain-side missile lairs can.

All told, it remains to be seen how far Iran decides to pursue this concept or whether they ultimately decide to abandon the idea just like the U.S. military did when deciding how it would field the LGM-118A Peacekeeper.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com