The YA-7F Strikefighter program looked to do something breathtakingly logical: take existing largely surplus A-7 Corsair II attack jets that lacked speed, maneuverability, and more advanced capabilities and turn them into a more agile supersonic night-fighting battlefield interdiction jets for pennies on the dollar compared to what a new airframe would cost. By all accounts, the YA-7F team was successful at doing just that, but they were fighting a losing battle due to a number of factors, the biggest of which was the latest rendition of the F-16, the Block 40/42 F-16CG/DG, and the love of pointy-nosed fighter jets among the Air Force brass. The fact that big defense contractors wouldn’t make a windfall revamping surplus A-7s probably also had something to do with it.

In the end, the far more expensive and sexy F-16, which was born a fighter, would be chosen over the utilitarian YA-7F for the nighttime battlefield interdiction mission, but in retrospect, that may not have been the best choice, at least entirely. You can read all about the YA-7F program and its potential in this past piece of mine, but now, thanks to retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell Burnside Clapp, we have an entirely new perspective on this enigmatic initiative from someone who was right there during the test program.

According to Clapp, the YA-7F was really an incredibly logical recycling program more than anything else. If it would have been greenlit into production, it probably would have been the most bang for the buck the Air Force had realized in an airframe in decades. It also would have been remarkably suited for the period of turmoil that would come a decade later in the air campaigns that followed the attacks on 9/11.

Lt Col Michell Burnside Clapo recounted the following about his time with the YA-7F program and its demise to The War Zone:

My first job out of Test Pilot School in 1988 was the YA-7F. The jet was great. The subtle changes in the aerodynamics really improved a lot of things, particularly handling at high angles of attack (AOA). We couldn’t even spin the jet even with adverse control inputs into the heavy wing with an asymmetric load. The avionics were the basic LANA suite (a “Low Altitude Night Attack” package that did pretty much what LANTIRN did later in the rest of the fleet). Some of the things we did during the test program less useful than hoped – loading the GPU-5/A gun pod was a good way to test vibration, but not a good way to actually hit anything on the ground with any accuracy. It was a great year of flying, and the test team hit all the points and demonstrated everything that the jet was supposed to do.

In the mid-1980s, it became clear that IPEs (Improved Performance Engines) would soon be available for the tactical air forces. These were the -129 and -229 variants of the General Electric and Pratt & Whitney fighter engines, respectively. I’ll talk about the Pratt engines from here onwards since that’s what we flew in the YA-7F, but feel free to assume that it’d apply to the GE engines, as well.

The then-current (i.e. -220) versions of the engine produced around 14,000 pounds of thrust in full military power (MIL) and 23,000 in max afterburner. The soon-to-be-available -229s, though, could produce 17,800 pounds in MIL and 29,000 pounds in max afterburner. The tactical fighter fleet was then full of hundreds of F-16 Vipers and F-15 Eagles with perfectly serviceable -220 engines. The -220 was the variant that had the digital engine controller and substantially improved maintenance and uptime over its predecessors, but the -229 would have been a serious improvement in performance.

It would have been great to re-engine all the tactical fighters in the ‘90s inventory, but that poses the question, what do you do with all the perfectly serviceable and relatively low-time -220s? A potential answer was the YA-7F Strikefighter.

At this point, in the mid-1980s, the only active-duty places still flying the A-7 were Edwards, for test support, chase, education at Test Pilot School, and so on, and at dark grey places in southern Nevada, where it was used to get enough flight time to maintain proficiency for the pilots of airplanes up that way that didn’t generate a lot of sorties. All the other remaining A-7s, D models, were in the Air National Guard. The Navy, the Portuguese, and the Greeks still had theirs, of course, but the Air Force’s A-7 fleet was a guard-only operation, and the guard was the customer, ultimately. The guard wanted F-16s, which, eventually, they got.

Consequently, the YA-7F never lost its “Y” (prototype) prefix and the 200-ish flight tests that took place, mostly in 1990, submitted a stack of technical reports and everybody dispersed. Conversion costs of the jet from D-model to F-model would have been, if memory serves me right, around just $7M per jet in 1990 dollars.

The aircraft only went supersonic to calibrate the air data system. There was no point in going that fast tactically. The extra thrust was more useful for shortening takeoff, maintaining speed during maneuvering, particularly during automatic terrain following, and accelerating from around 300 to 500 knots, in the tactical speed range. Mostly the jet was about delivering bombs on target. While the top speed may have theoretically been around 1.6 Mach, it would have taken you all afternoon to get that fast and you were likely to run out of gas on the way.

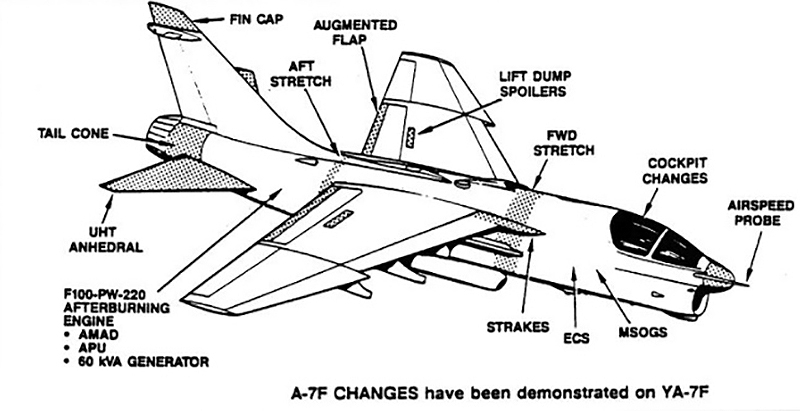

The fuselage was stretched four feet in total. Two and a half feet were in front of the wing and one and a half feet were behind it. Because of the stretch, the aft fuselage had to be canted upwards a little bit to maintain ground clearance. That caused the horizontal tail to get hammered in the wake of the main wing. That problem turned out to be fixable with a change in the dihedral angle to a slightly negative value of about five degrees. It turned out that putting the left horizontal tail on the right side and vice versa managed to solve the problem completely and was only a half-degree off optimum.

The stretch included room for extra gas, which, if you didn’t use the burner, could have improved the endurance of the already-long-legged basic jet. After all, the ‘unaugmented’ thrust was the same for both D and F, around 14,000 pounds of thrust. There was a minor concern at one point that the jet in afterburner could accelerate fast enough on takeoff to overspeed the gear during transition, but I don’t think that particular problem actually manifested in flight.

The vertical tail basically had its tip cleaned up and extended a bit, which wasn’t a big change. It probably helped a little at high AoA, though. The big help was from the leading edge extensions. There was a syllabus ride at Test Pilot School to do A-7 departures with a variety of entries and all the F-model pilots repeated it in the A-7K (two-seater standard model) that the program used for chase duties during test flights.

You could get the basic A-7 to do some pretty violent things with adverse control inputs, but the F model was very resistant to that. You could keep it heading not-very-pointy end forward with a little attention to the rudder pedals at angles of attack at which you already would have been out of control in the D model. D model recoveries were nearly always “ailerons into the spin,” the F model was the same, but frankly “just grab the mirrors” would have worked just as well.

The engine was great and that was particularly true in formation flight and rejoins. The original turbofan in the D model had a lot of lag and sometimes it felt like you were communicating with the engine by mail. You had to be ahead of the jet to fly in company, which is never a bad thing airmanship-wise, but the new engine was much more responsive.

Other mods on the jet were an OBOGS – an onboard oxygen generation system – which filtered compressor bleed air to remove most of the nitrogen. Not all, though – it was still about seven percent N2. That made some of the air start testing a bit challenging because the pilot was still going to have some N2 in his blood, which raised the risk of decompression sickness if there was a loss of cabin pressure, which should be expected if you shut the engine off.

YA-7F tail number 344 had a metal piece covering its turkey feathers – the moveable nozzle parts at the exhaust end of the engine. About halfway through the test program that part was removed. It turned out that the turkey feathers were being drawn outwards slightly by suction between the nozzle flaps and the tail cone extension and the engine controller wasn’t reading the position of the flaps accurately. When the part was off, the performance of the jet improved a little and that was the configuration we completed the test program in. The other jet, 039, kept its extension because that was where the spin chute was mounted and that was the jet we used for all the high AoA testing.

The basic requirement for the flight tests was “fly no worse than the A-7D” and it was achieved. For test planning purposes, we were in the odd position of having to test with respect to an outdated specification – MIL-F-8785B – Charlie was the current version at the time. The original test report’s lead engineer was… Burt Rutan! He wrote it during his active duty tour in the mid-1960s.

All in all, the YA-7F did what it was supposed to do and did it well. The modification team and test team ran a fairly fast, efficient, and comprehensive program, and the transition to production would have resulted in a solid Close Air Support/Battlefield Area Interdiction capability. It was originally called the “A-7 Plus” by LTV, its manufacturer (occasionally some wit would call it the “F-8 Minus”) before it received its official designation. But a fleet of A-7Fs was not to be, because the Guard was holding out for moving up to the F-16, which is inherently far more multi-role capable than the unlovely YA-7F variant of the SLUF (slightly longer ugly fellow).

Editor’s note: A big thank you to Lt Col Mitchell Burnside Clapp USAF (ret), who currently works at Embassy Aerospace LLC, for sharing his YA-7F memories with us.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com