Members of the U.S. Marine Corps’ 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment recently took part in mountain warfare training with the help of a small 6×6 wheeled Hunter WOLF unmanned ground vehicle. This unit is one of three experimental Marine battalions that the service is using to evaluate and refine its new expeditionary and distributed warfighting concepts, and new weapons and equipment to go with them, which is all part of an extensive service-wide force restructuring effort.

Elements of B Company, 1/2nd Marines, part of the 2nd Marine Division based at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, conducted the mountain training at Camp Dawson, West Virginia just in the past week or so. Earlier today, the 2nd Marine Division’s public affairs office released pictures, which were taken on Feb. 5, 2022, showing them working with the Hunter WOLF unmanned ground vehicle (UGV).

HDT Global, which is headquartered in Ohio, began development of the Hunter WOLF in 2012. The WOLF part of the name stands for Wheeled Offload Logistics Follower. “Follower” in this case reflects one of the unmanned vehicle’s primary modes of operation, in which it automatically trails behind an operator holding a hand-held wireless controller. That system can also be used to remotely operate the UGV. The manufacturer is working to integrate additional autonomous capabilities onto the platform, as well.

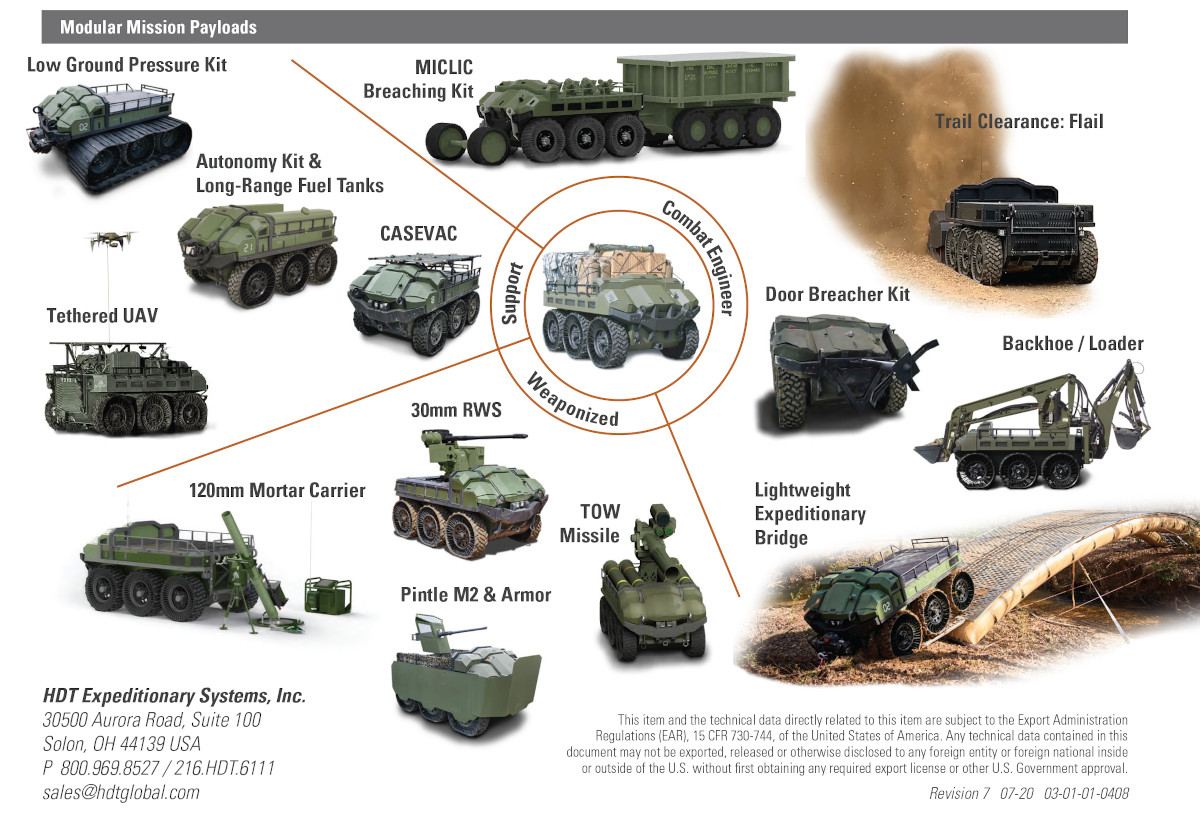

The relatively small 6×6 vehicle, which weighs around 3,600 pounds, is a modular design capable of carrying various payloads weighing up to 2,200 pounds. It has a hybrid-electric propulsion system that allows it to travel as far as 200 miles or otherwise operate for up to 120 hours on a single tank of gas – either JP-8 jet fuel or diesel. Range-extending fuel tanks are available.

An onboard generator can provide up to 20 kilowatts of power to support sensors, remotely operated weapon stations, and other systems, as well as provide 15 kilowatts of electricity to run offboard systems. The vehicle can also move or operate in a static position in a “silent” mode to help reduce the chance of enemy forces detecting it and the troops it is working with.

During the recent mountain warfare training in West Virginia, Marines appear to have utilized this UGV to help move equipment and supplies, as well as evacuate a simulated casualty. HDT Global lists these mission sets among a broad array of roles that appropriately configured Hunter WOLFs might be able to perform.

HDT Global says the Hunter Wolf can be configured to perform mine-clearing, limited battlefield engineering work, direct and indirect fire support, and other missions. The vehicle can be equipped with a quad-copter unmanned aerial vehicle on a tether, which could allow it to act as a communications relay node. That small drone might be able to carry full-motion video cameras to give the combined unmanned platform an expanded surveillance and reconnaissance capability or just provide general localized situational awareness.

This is not the first time that the Marine Corps has explored the capabilities the Hunter WOLF has to offer, as well as those of other unmanned ground vehicles. However, integrating new unmanned platforms, on the ground, as well as in the air and at sea, are key components of the service’s ongoing force restructuring, called Force Design 2030, which you can read more about here. As already noted, 1/2nd Marines is one of three battalions that the Corps is using to evaluate different infantry force structure configurations.

The goal of Force Design 2030 is to enable new expeditionary and distributed warfare concepts of operations, known collectively as Expeditionary Advance Base Operations (EABO). At EABO’s core is the idea that relatively small groups of Marines will be able to rapidly deploy to remote or austere locations, especially islands in the Pacific region, and establish forward bases. From these locations, the hope is that they will be able to employ a wide array of capabilities to deter a potential enemy and, if a conflict does break out, be well-positioned to respond. These contingents should also be able to quickly redeploy, either in response to new developments in the battlespace or to help upend an opponent’s decision-making cycles.

The Marine Corps sees UGVs as an important way to expand the capabilities and general operational capacity of these distributed contingents without having to significantly enlarge their overall force size. The mobility and transportability of these platforms are also important factors in this calculus. HDT Global says that a Marine MV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor can carry two Hunter WOLFs internally. It’s not clear how many might be able to fit inside one of the service’s new CH-53K King Stallion heavy-lift helicopters, but a CH-47 Chinook can accommodate six inside its main cargo cabin, according to the manufacturer.

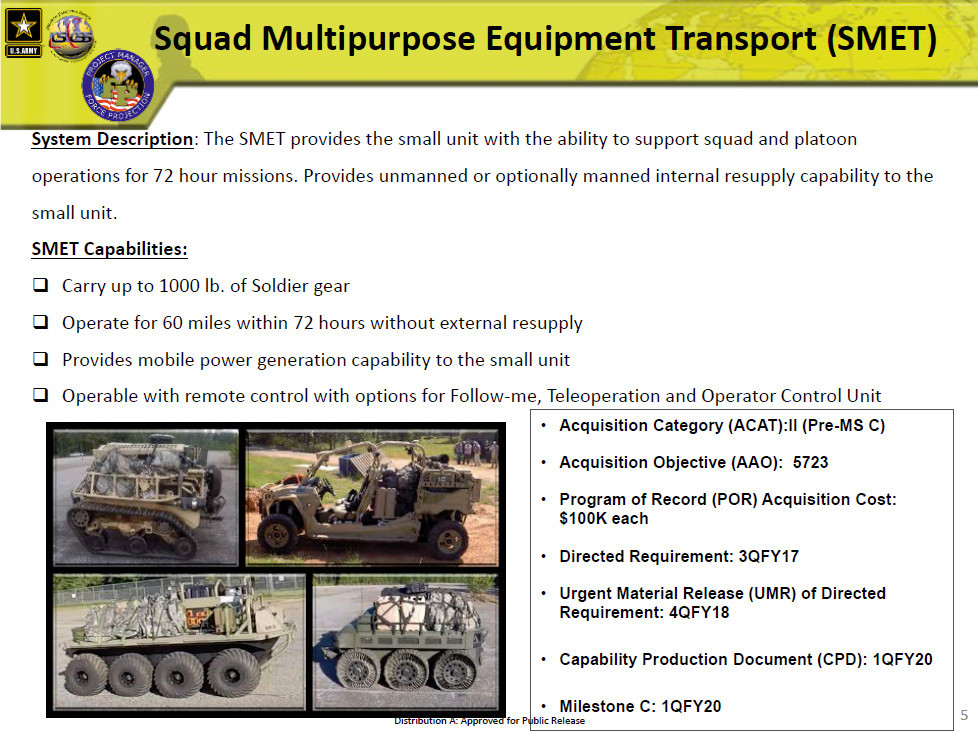

The Marines are not alone in being interested in exploring the benefits that UGVs have to offer ground forces. The U.S. Army is currently looking to acquire a number of different sizes of unmanned ground platforms to meet a variety of different requirements. During one exercise last year, armed Army UGVs under the control of mock enemy forces helped deny access to helicopter zones and defend static positions, among other tasks, highlighting the diversity of missions that unmanned platforms could perform in the future.

The Hunter WOLF itself had competed for the Army’s Squad Multipurpose Equipment Transport (SMET) contract, initially losing out to General Dynamics Land Systems’ Multi-Utility Tactical Transport (MUTT). However, a subsequent protest by another competitor, Howe and Howe, led to the Army cancel that deal and reboot the competition, inviting all of the original participants to resubmit their designs. HDT Global says that U.S. Special Operations Command has also evaluated the Hunte WOLF separately.

What kind of UGVs ultimately end up in the Marine Corps’ infantry battalions, as well as other Marine units, remains to be seen. “Everybody’s hungry for more capabilities, everybody is interested in getting more of the enhanced capabilities that we’re providing,” Gen. Benjamin Watson, head of the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, as well as the service’s Futures Directorate and as Vice Chief of the Office of Naval Research, told Defense One last year in regards to the three experimental units.

“But quite frankly we’re a people-centric organization, and we believe this is more, first and foremost, about the development of the individual Marine and the organizational structure, and less about the technology,” he added. “But both are required.”

What one sees in the recent pictures from Camp Dawson is certainly indicative of the kind of mixture of people and technology that Gen. Watson was talking about. As time goes on, images of Marines trekking around, whether it’s in the mountains of West Virginia or somewhere else, together with a Hunter WOLF or some other kind of UGV, are only likely to become more commonplace.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com