The U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division has posted videos online of troops from its 1st Brigade testing a new small unmanned ground vehicle, or UGV, called the Punisher. The evaluation is part of a larger program, which is looking to develop a system to help carry equipment and provide mobile power generation for small infantry units. But the vehicles could take on additional missions in the future, acting as weapons carriers, small ambulances, and more.

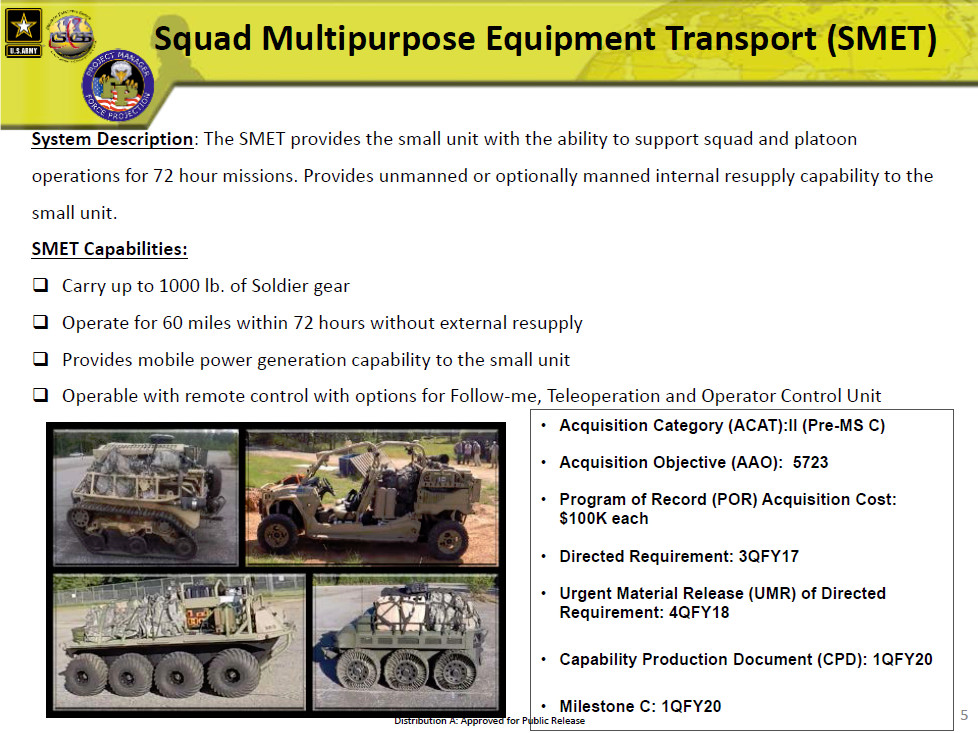

The 10th Mountain is conducting the evaluations within the latest iteration of the division’s major readiness exercise, nicknamed Mountain Peak, which began in the training areas outside of Fort Drum, New York in November 2018. Various units within the 1st Brigade will use the Punisher, a product of the Maine-based firm Howe & Howe, along with the Polaris MRZR-X, the 8×8 version of General Dynamics Land Systems’ Multipurpose Unmanned Tactical Transport (MUTT), and the HDT Global Hunter Wheeled Offload Logistics Follower (Hunter WOLF). Troops will report back with their findings to the officials in charge of the Army’s Squad Multipurpose Equipment Transport (SMET) program.

“I’m not an Infantry Soldier,” U.S. Army Captain Erika Hanson, the Assistant Product Manager for SMET, told the service’s reporters in June 2018. “But I’ve carried a rucksack – and I can tell you I can move a lot faster without a rucksack on my back. Not having to carry this load will make the Soldier more mobile and more lethal in a deployed environment.”

In December 2017, the service chose the present field of four vehicles from a total of eight to proceed to the SMET program’s operational evaluation phase with the 10th Mountain Division. The 1st Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division is also conducting an evaluation of the same unmanned vehicles.

The MUTT and Hunter WOLF are both wheeled platform designs, while the entrant from Howe & Howe, now a division of defense contractor Textron, is the only tracked type remaining. The MRZR-X, which Polaris developed in cooperation with Applied Research Associates Inc. and Neya Systems LLC, is an optionally-manned version of the first company’s popular MRZR all-terrain vehicle. This vehicle is already in service with U.S. special operations forces, the Marine Corps, and some conventional Army units.

The basic SMET requirements are for an unmanned all-terrain transport vehicle that can carry up to 1,000 pounds and be able to travel 60 miles in total over a 72 hour period without needing to refuel its gas tanks or recharge its batteries, depending on propulsion method. The vehicle must have a power generation system, as well, that can support an ever-expanding array of electronics, including communications gear, hand-held sensors, portable navigation systems, and electronic warfare equipment, that small Army units carry with them even on short-duration operations.

Troops will be able to operate these “robotic pack mules” using controls on the vehicle itself or a handheld controller. The portable system will also have a video screen linked to cameras on the UGV to allow for remote operation. A “follow-me” functionality, in which the vehicle will keep a set distance between it and the control system at all times, is also a requirement.

“Nine ruck sacks, six boxes of MREs, and four water cans,” was a notional load Captain Hanson used to describe the desired payload capacity for the SMET. “This is about the equivalent of what a long-range mission for a light Infantry unit would need to carry.”

With the unmanned transporter, the squad- or platoon-sized unit would be able to carry even more weapons, ammunition, equipment, and other gear, or be able to reduce the physical workload on individual soldiers. At present, dismounted Army infantry soldiers are easily carrying close to, if not more than 100 pounds for even relatively short-term missions.

The service is looking for ways to lighten individual

pieces of equipment, but is also looking to add more capabilities on top of the existing load outs. New electronics will also require recharging in the field, a critical capability that the SMETs will be able to provide, as well. As such, the unmanned vehicles may be an increasingly necessary addition to small units.

The vehicles could also take on other roles beyond simple cargo carrying in the future. In her June 2018 interview, Captain Hanson described one novel application, where troops put a radio on the UGV and sent it out to a remote point to act as a communications relay without putting personnel at risk.

With a 1,000-pound payload capacity, the vehicles have the capacity to serve as mobile platforms for weapons that would be too heavy for dismounted infantry to carry with them on routine patrols and short-range operations. HDT has already shown off a version of the Hunter WOLF equipped with a .50 caliber machine gun on a remote weapon station. Howe & Howe derived the Punisher, which the 10th Mountain’s soldiers are already confusingly referring to by the separate name Grizzly, from its earlier RS2-H1 design, which featured a similar weapon system, as well as equipment to disable or destroy improvised explosive devices and mines.

Those same weapon stations could accommodate anti-tank guided missiles, such as the FGM-148 Javelin, or grenade launchers for additional firepower. The Army is looking to add launchers for small drones and loitering munitions on manned and optionally-manned armored vehicles in the future, which is another option for even small unmanned systems. This would help improve a unit’s situational awareness and give it another option to conduct indirect attacks on opponents.

Combined with a semi-autonomous route following capability or beyond-line-of-sight control systems, the vehicles might be able to rush badly needed supplies to frontline units without risks to manned logistical vehicles or aircraft. Those same unmanned systems could load up any casualties and race them back to more established medical facilities.

Though unmanned vehicles offer significant benefits for small unit operations, there will still be challenges if the Army decides to introduce them on a wide scale. For one, they are substantially larger than anything a dismounted infantry unit is expected to carry at present and if they were to break down for any reason, soldiers might be forced to, at least temporarily, abandon the vehicle and some of the cargo it might be carrying.

Small units will also need to train to perform basic maintenance on these vehicles in the field. The requirement for a total operating range of 60 miles over three days without resupply might clash with the Army’s recently articulated desire for brigade-sized units to be able to operate for at least a week without outside logistical support, as well.

These are hardly new issues for the Army, which has been looking to acquire a fleet of small unmanned vehicles to help reduce combat and logistical burdens on small units for more than a decade. The infamous and now-canceled Future Combat Systems (FCS) program included the XM1217 transport unmanned ground vehicle.

But the technology required for unmanned ground vehicles, especially semi-autonomous designs, has come along way since the Army canceled FCS in 2009. The significant progress in the commercial sector on self-driving trucks and cars, in particular, has been a game changer and has only bolstered continued developments within the U.S. military. Advances in electric and hybrid-electric drive systems and associated power sources, including hydrogen fuel cell technology, have also pushed the idea of unmanned ground combat vehicles closer to reality.

The U.S. Marine Corps has also taken note and has been evaluating unmanned ground vehicles, including the 4×4 version of the General Dynamics MUTT with tracks in place of wheels and the HDT Hunter WOLF, for some time. The Corps is interested in these vehicles for both cargo-carrying tasks and as mobile fire support platforms. The two services might well find themselves cooperating on a joint effort to field unmanned ground vehicles in the near future.

The Army hopes that the SMET program will pick a winning design by 2020 and have the first examples actually operational by 2021. The service says it could buy more than 5,700 of the small unmanned ground vehicles in total.

If the project proceeds as planned, it might not be too long before soldiers are conducting operations with unmanned partners to carry their supplies and more.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com