As the historic Norwegian airbase at Bodø, located within the Arctic Circle, closes down today as a fighter jet station, it’s a good time to look back at one of the more secretive aspects of the base. It played the role of a vital node in the early days of the U-2 spy plane. Ultimately, this little-known chapter in aerial espionage came to an end on May 1, 1960, when a U-2 flown by Francis Gary Powers was shot down by a surface-to-air missile deep over Soviet territory. Powers had been due to complete his flight by landing at Bodø, but the international incident that followed his shoot-down led to the abrupt termination of such deep-penetration missions.

Bodø, more formally Bodø Main Air Station, was for many years one of the most important fighter bases for the Royal Norwegian Air Force, or RNoAF, most recently operating F-16s. With the continued arrival of the F-35A stealth fighters, 52 of which are on order for Norway, the base today lost its fighter mission and the Joint Strike Fighter has assumed quick reaction alert (QRA) duties.

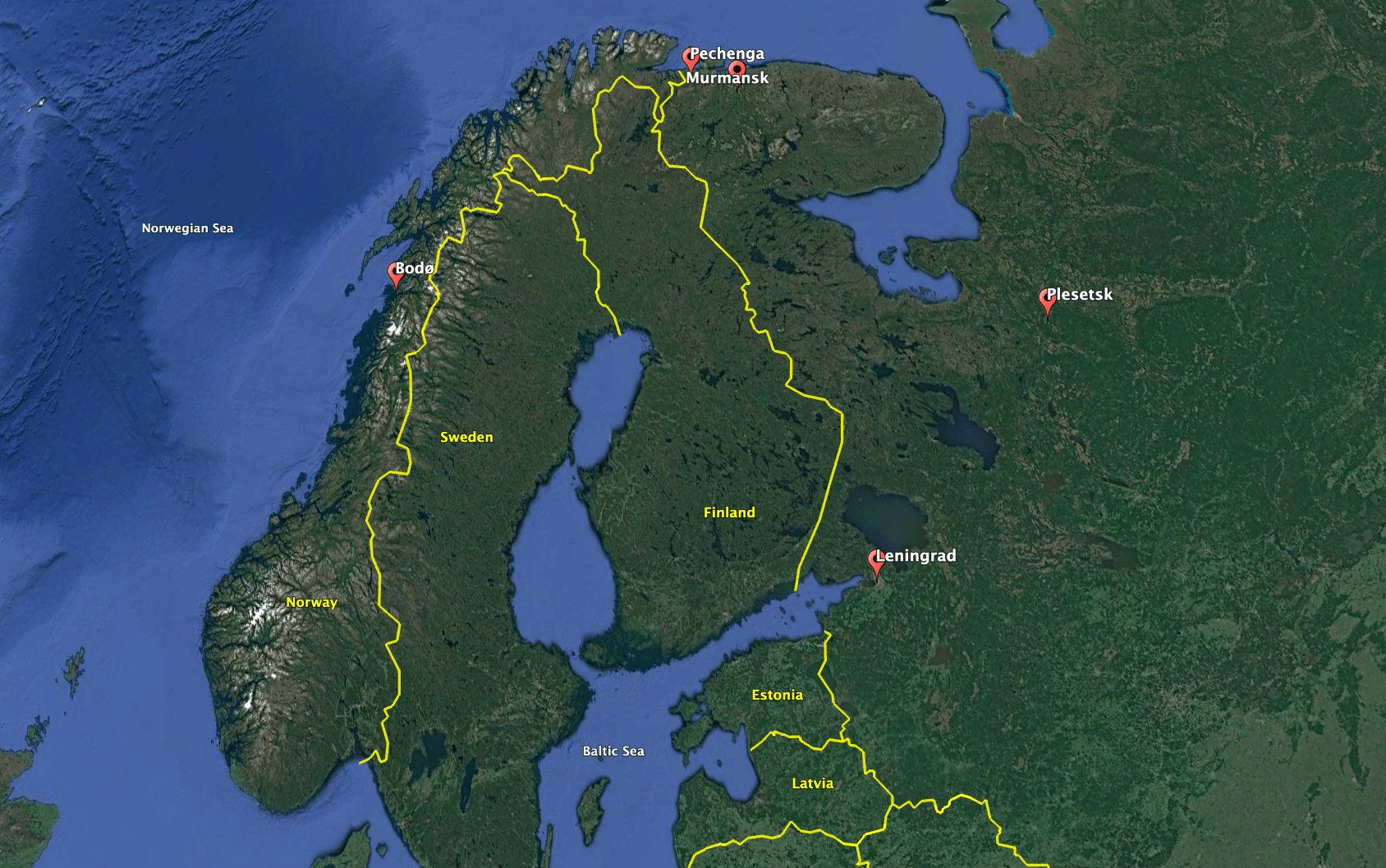

While the military use of the airfield at Bodø dates back to before World War II, the base really came into its own with the start of the Cold War, thanks to its strategic position close to the border with the Soviet Union. The distance from Bodø to Russia’s massive naval base and port at Murmansk is just 500 miles, and with Norway becoming a founder member of NATO in 1949, work soon began to expand the airbase as a springboard for alliance airpower on the Northern Front.

Ultimately, a great deal of Bodø’s strategic value would come to be derived from its proximity to the Soviet Northern Fleet, which would eventually possess most of that country’s ballistic missile submarines and significant surface forces. Before then, however, the Soviet nuclear deterrent relied on manned bombers and early intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Since the first Soviet ICBMs still lacked the range to reach all potential targets in the United States, they had to be located in the far north of the Soviet Union, from where they would be launched on a polar trajectory.

The first Soviet ICBM — in fact, the first anywhere in the world — was the R-7 Semyorka, known in the West as SS-6 Sapwood. It shared the same technology as the rocket that launched Sputnik 1, as well as the Vostok and Soyuz space-launch vehicles, among others. When the Soviets began to construct an operational launch site for SS-6 ICBMs at Plesetsk, near Arkhangelsk, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was understandably eager to learn more.

The CIA’s attention turned to gathering aerial espionage with overflights by its U-2s over the northern reaches of the Soviet Union, and they requested the use of Bodø for this new mission. Norway agreed on the basis that these flights would not penetrate Soviet airspace. The CIA provided this guarantee, but, with Presidential approval, its U-2s were still able to conduct clandestine overflights of the Soviet Union. For now, though, the Norwegians were kept in the dark.

As well as the ICBM base at Plesetsk, there were concerns that the Soviets were also rapidly improving their air defenses, which would make them better able to protect their northern frontiers against incursion by U.S. Air Force strategic bombers. A chief item of interest in this regard was the PRV-10M, or Patty Cake, a height-finding radar associated with the SA-2 Guideline surface-to-air missile.

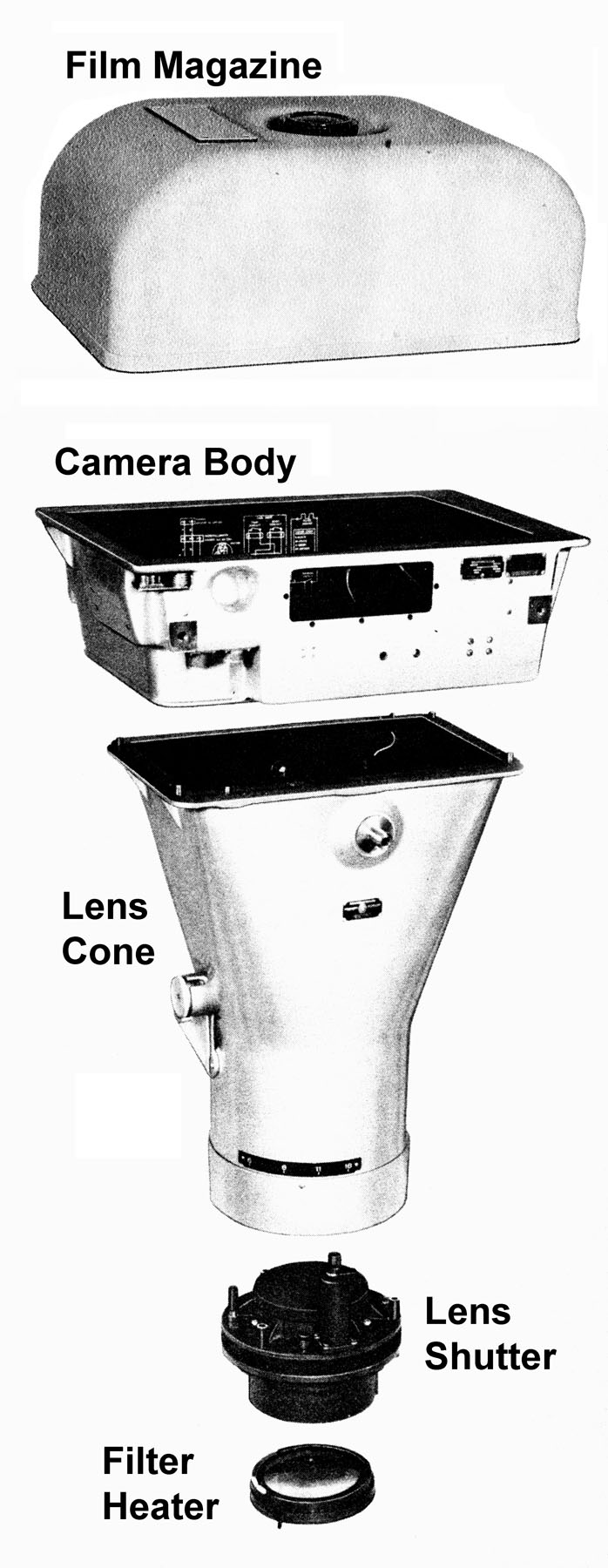

In 1958, the still highly classified U-2 was determined to be the best platform to discover more about Plesetsk and developments in Soviet ground-based air defenses. In addition to its array of optical cameras, the aircraft carried electronic intelligence (ELINT) equipment that would be able to gather emissions from the Patty Cake system, while its high-altitude performance was expected to guarantee not only its safety but also more extensive coverage.

By May 1958 the CIA had decided on a two-track approach for the northern U-2 missions from Bodø. One route would take the aircraft across the Barents Sea for overflights of Plesetsk, requiring Presidential authorization, while the other was less sensitive and would see the aircraft operating over international waters in the Gulf of Finland. To provide a cover story for the Norwegians, the CIA asserted that the U-2 missions were related to atmospheric sampling in the wake of Soviet nuclear tests taking place at Novaya Zemlya. In any event, this would turn out to be partly true, although weather reconnaissance was an early cover story for U-2 operations.

It seems the Norwegians very likely understood that there was something more to the U-2 missions, despite reassurances they would not involve overflights. The head of military intelligence in Oslo, Col. Vilhelm Evang, was of the opinion that more information should be provided to explain any future such CIA missions. At the same time, the Americans also distrusted Evang, who some officials alleged was a communist.

Despite reservations, the CIA launched Operation Baby Face in August 1958. A month later, the first of three U-2s involved in the mission touched down at Bodø and soon began local training flights. As well as the U-2s, a total of 16 or 17 transport aircraft — mainly U.S. Air Force C-130s — were also involved as support assets.

Two operational flights took place over the Barents Sea in October 1958 but didn’t involve overflights. The first of these was genuinely used for sampling near Novaya Zemlya. The second was planned as an overflight, but had to be aborted after the CIA pilot noticed fuel was running low. However, by approaching close to Soviet airspace, the U-2 put Soviet air defenses on alert, with transmissions being picked up in turn by the Norwegians. Once again, Norwegian officials became concerned about the nature of the U-2 missions.

By November, the weather was deteriorating, and the CIA decided to launch one last mission in the direction of Leningrad, with the aim of approaching as close to the city as was possible, while remaining in international airspace.

With CIA pilot John Shinn at the controls, the U-2 launched from Bodø on Nov. 6, 1958, fitted with long-range fuel tanks that would allow it to fly all the way to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. The Norwegians were not informed of the departure. The spy plane was detected by Soviet radar when west of Pechenga on the Finnish-Soviet border. It then continued south through Finland, into the Gulf of Finland, and toward Leningrad. The U-2 then turned west again, through the Gulf of Finland and over the Baltic Sea.

Soviet air defense radar mistakenly identified the U-2 within its airspace in Estonia, leading to five MiG-19 Farmer interceptors being scrambled from their bases in Estonia and Latvia. The Soviet fighters topped out at 53,800 feet, leaving the U-2 unscathed at its perch of over 60,000 feet. The U-2 continued its mission, flying over West Germany, Italy, and Greece, before landing at Incirlik. The CIA later estimated that a total of 57 Soviet fighters were launched against Shinn’s aircraft at different points during the mission, providing a valuable ELINT windfall.

While the November 6 flight brought good intelligence results, the fact that it was a CIA mission led to displeasure in the Air Force, which saw missions of this type and in this region as part of its remit. The Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed, even though Air Force U-2 missions were not permitted to overfly Soviet territory so were inevitably more limited in the intelligence they could target.

As it was, the November 6 flight was the last by a U-2 involving Bodø until the ill-fated Powers mission of May 1, 1960. As is well known, that U-2 flight was fated never to reach its Norwegian destination. It was, of course, an SA-2 Guideline — one of the systems that Operation Baby Face hoped to discover more about — that blasted Powers’ U-2 out of the sky over Sverdlov.

The U-2 crisis of May 1960 saw relations between Oslo and Washington sour. As soon as it became clear that the CIA was using Bodø to fly over the Soviet Union, Norwegian officials requested that U.S. personnel supporting the missions leave the base. Such was the hurry for the CIA team to leave the installation that they departed, together with their equipment, using an available U.S. Air Force C-130 Hercules with only three working engines.

While overflights of the Soviet Union came to an end, the U-2 remained engaged on vital intelligence-gathering missions elsewhere in the world, a role in which it continues to excel to this day, despite more than one effort to retire it.

In the years after the U-2 incident, Bodø served primarily as a fighter base for the Royal Norwegian Air Force, or RNoAF, although on at least two occasions it became an emergency landing site for SR-71 Blackbird spy planes. Successive generations of RNoAF fighters — F-84G Thunderjets, F-86 Sabres, F-104 Starfighters, F-5 Freedom Fighters — all served at the base, which would have been expected to host other NATO assets to protect the alliance’s northern flank in times of crisis.

NATO funded infrastructure improvements at Bodø, including dozens of underground hangars to protect aircraft against Soviet attack. Meanwhile, the resident fighters kept a near-constant watch on Soviet military activities in the Barents Sea and the Norwegian Sea, frequently intercepting aircraft and shadowing naval maneuvers.

Bodø’s fighter mission has now finally come to an end with the stand-down of the RNoAF’s F-16s at the base. From now on, air defense duties, including quick reaction alert (QRA), will be handled by the service’s F-35s. These will be stationed at Ørland, in central Norway, with a detachment at an advance base at Evenes in the north. In the future, Evenes will also host RNoAF P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft and will become a much more important installation as Norway continues to address the resurgent military threat posed by Russia. As for the F-16s, some of these have been snapped up by adversary air support contractor Draken International, while the Romanian Air Force has made moves to secure 32 of the others.

From now on, the only regular military aircraft activities at Bodø will involve a small detachment of search-and-rescue Westland Sea King helicopters of the RNoAF. But with such a rich Cold War heritage behind it, and with the Norwegian Aviation Museum on the same site, the legacy of Bodø Air Base is unlikely to be forgotten.

With thanks to Robert S Hopkins III, whose forthcoming book, Crowded Skies: Cold War Reconnaissance over the Baltic, provides more details of the U-2 operations from Bodø.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com