The story of Lockheed’s F-22A Raptor stealth fighter has been and remains contentious in many ways, especially with regards to the short-sighted decision to curtail its production run and debates over whether or not to start building them again. The matter of exporting the jets still stirs strong opinions more than a decade after Congress made it impossible to do so for fear of the secrets of the aircraft’s many sensitive components and capabilities leaking out. However, lawmakers did also ask the U.S. Air Force to look into exactly what it might take to make an export version of the F-22, and The War Zone has now obtained a declassified copy of a detailed briefing into just what that study found.

The Air Force released a heavily redacted, though still extremely insightful copy of this briefing, which is titled “F-22 Export Configuration Study” and is dated March 2010, in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The War Zone had sought this document, which says the full unredacted version includes information that is still tightly controlled under multiple Special Access Programs (SAP), after noticing it among the references included in an unclassified report that the service sent to Congress about restarting F-22 production in 2017. You can read more about that more recent study here.

The Special Programs Division of the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition led the work on the export study. The Global Power Division of that same office, as well as the Regional Affairs Division of the Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of the Air Force for International Affairs, also supported the effort. The 478th Aeronautical Systems Wing, which served as the F-22 System Program Office (SPO), as well as the Air Force’s Office of Operational Capability Requirements and Air Combat Command’s (ACC) 5th Generation Fighter Division, participated, as well. The complete group responsible for the study also included personnel from an Air Force Red Team, as well as the Air Force Office of Special Investigation’s (AFOSI) Region 7.

The Air Force had been required to conduct this study into the feasibility of an export-configured F-22 through a provision in the “SAP Annex of the 2009 Appropriations Bill,” according to the briefing. The document also says that service requested and got approval from the Senate Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Defense for more time to complete this report, work on which only started in December 2009. The Air Force had already conducted one F-22 export study, together with Lockheed Martin, in 1998, and a Red Team from the service had also reexamined security concerns around transfers of sensitive technologies associated with the Raptor in 2006. Lockheed Martin had carried out its own internal export feasibility review in March 2009, as well.

In April 2009, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates had announced his fateful intention to dramatically curtail F-22 purchases for the U.S. Air Force, something the service had acquiesced to in no small part to ensure continued funding would be available for what would become the B-21 Raider stealth bomber. Despite initial opposition, Congress agreed to the plan in July of that year in the face of a threat from President Barack Obama to veto any appropriations bill that included money for additional Raptors.

In June 2009, Reuters had also reported that legislators were considering asking the service this new F-22 export study. This had apparently come up in response to one of the Japanese government’s many overtures over the years expressing interest in buying F-22s. Japan had inquired on multiple occasions about the possibility of acquiring Raptors, despite the passage of an amendment to another bill in 1998, put forward by David Obey, then a Democratic Representative from Wisconsin and Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, which had blocked any potential exports of these jets. Israel and Australia had also shown robust interest in purchasing Raptors.

All of this had an impact on the various ground rules and assumptions the group working on the study set as their starting point, as well as the potential courses of action they ultimately crafted. For instance, the study team outlined a notional export F-22 derived from the expected configuration, Increment 3.1, of the last Raptors on order for the Air Force. They also explored cost considerations based on the possibility that the production of jets for Foreign Military Sales (FMS) customers could immediately follow the service’s own final orders, as well as what might happen if the production line went cold for a time after the last of those aircraft were built.

The study produced two core cost and schedule estimates for a notional F-22 FMS program. Option 1, which factored in a two-year pause in Raptor production, would cost approximately $11.6 billion, overall, including a production run of 40 aircraft, each with an average unit cost of $232.5 million. In today’s dollars, that would equate to an average unit cost of just under $259 million and a total cost of nearly $13 billion. Under this course of action, the Air Force estimated that the first FMS Raptor would be delivered around six and a half years after the award of a formal contract to begin developing the expert version of the jet.

Option 2, with a total estimated cost of $8.3 billion, or around $9.2 billion in 2021 dollars, was based on the possibility of work on FMS F-22s beginning immediately after the end of production of the jets for the Air Force. The potential cost savings came from not needing to spend any more on restarting the Raptor line, as well as lower expected unit costs, only $165 million per jet, or close to $184 million in today’s dollars, which would have come from various efficiencies gained from continuous production.

It is worth noting that neither option included any estimates about cost impacts from industrial or financial offsets on the part of any FMS customer or potential benefits in this regard to the U.S. government. Exporting F-22s would have helped push down procurement and operating costs for all countries flying versions of the jet. At the same time, they also did not factor in any additional costs associated with training or other support requirements that any American ally or partner would have had in standing up a Raptor force. Option 1 also assumed that Lockheed Martin would pause, not completely halt F-22 production, meaning that at least some elements of the production line would have remained in place, reducing the estimated costs associated with restarting work on the jets.

Actually building the jets was a central issue in the study and the proposed 40-aircraft production run accounted, by far, for the largest chunk of the estimated costs under Options 1 and 2. However, just developing an exportable Raptor presented significant challenges. Unlike the stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which was also in development at this time, as well as previous non-stealth American fighter jet designs, the F-22 had not been designed with any consideration for export potential. The F-22 is packed full of sensitive technologies, from its low-observable structures and coatings, right down the fasteners that hold parts of the airframe together while helping it maintain its stealth capabilities.

While there was export precedent in 2009 for some of the technologies found in the F-22 thanks to the F-35 program, the Raptor had at least three groups of systems and associated capabilities that the U.S. government had never allowed to go into a fighter destined for a foreign ally or partner. One of these technology groups included the Raptor’s advanced 2-D thrust vectoring and super-cruise capabilities, according to the briefing. What is included in the other two groups is entirely redacted, underscoring the sensitivity of those technologies, even now. Of course, details about many of the F-35’s critical technologies, which have been approved for export, are also blacked out.

The notional export-configured F-22 that the study outlined actually leveraged some of the work being done on the F-35. This proposed FMS Raptor would notably have featured the Joint Strike Fighter’s AN/APG-81 active electronically-scanned array (AESA) radar, rather than the original AN/APG-77, which is not found on any other aircraft. The AN/APG-81 was itself derived, in part, from the AN/APG-77.

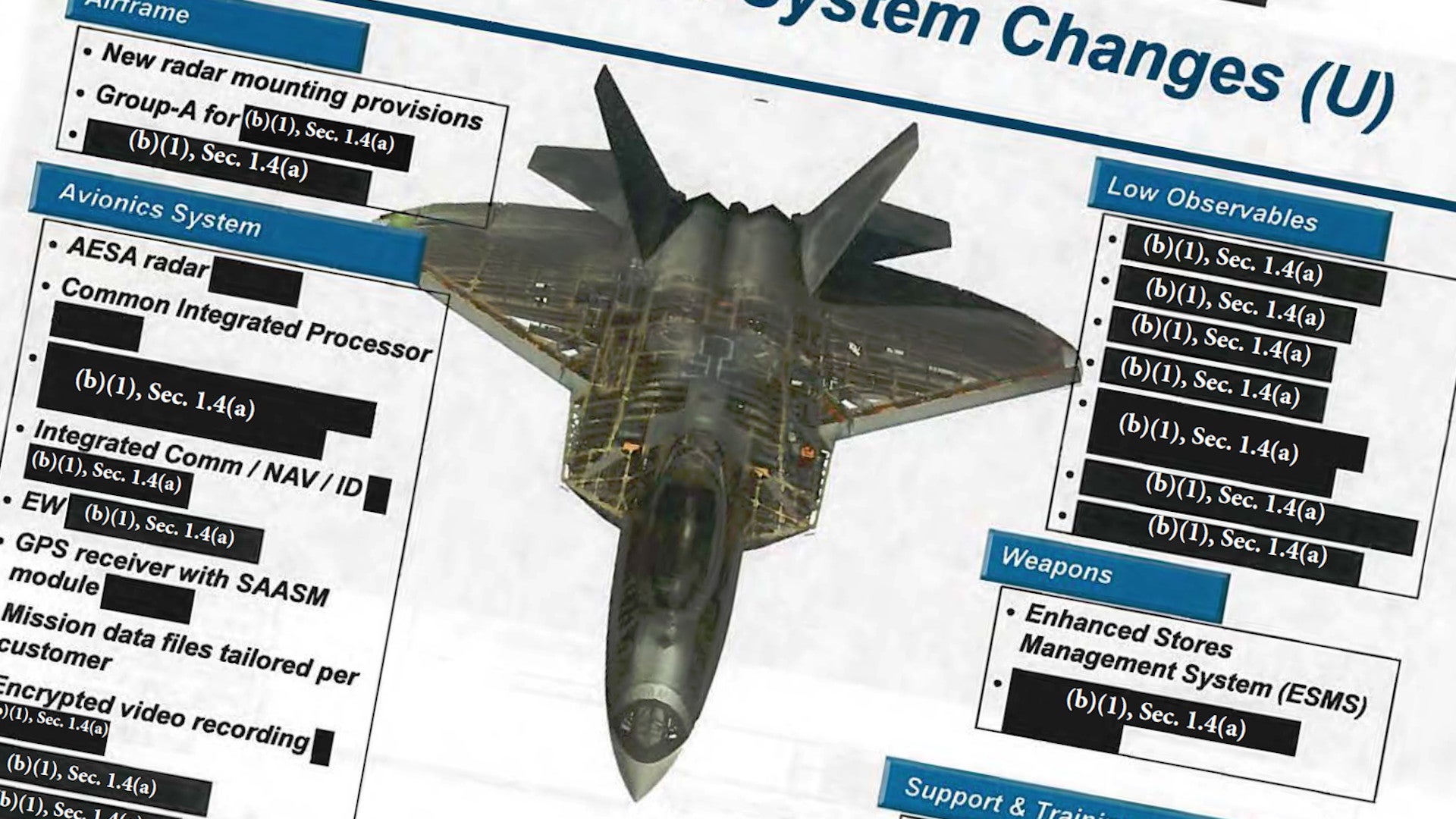

The export derivative of the Increment 3.1 F-22 would have needed some structural design to accommodate the AN/APG-81, among other things. The briefing also says that there would have been numerous changes, most of which are redacted, to the aircraft’s avionics, including “mission data files tailored per customer,” as well as to its low-observable (stealthy) features and coatings, what weapons it could carry, and associated support and training systems.

The Air Force did work with the assumption that there would be no local production in any way for the jets, which would be “end-item only,” again, something that is not the case with the F-35. “No software source code or software documentation will be exported,” the briefing adds. “Training and support will be provided under US controls to minimize the redesign required.”

Training and other support for export F-22s did raise additional issues given how deeply integrated Lockheed Martin was, and still is, in the operation and sustainment of the Air Force’s Raptor fleet. When this export study was conducted, the service was paying, on average, approximately $3 million, or just over $3.75 million in today’s dollars, for Contractor Logistics Support per aircraft every year. That figure did not include overhauls to each jet’s two Pratt & Whitney F119 engines.

In addition, the “USAF paradigm must change to provide ‘Operational Sovereignty’ to customer (i.e., no Lockheed Martin personnel in maintenance force that must deploy with units),” the briefing notes at one point. This is also interesting in the context of persistent questions about the actual extent of operational sovereignty when it comes to the F-35, particularly when it comes to the limitations imposed by the need for operators to use the associated cloud-based Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), which you can read more about in detail here. To date, only one F-35 customer, Israel, has secured the ability to fly its jets entirely independent of the ALIS network, which is now slated to eventually be replaced by the Operational Data Integrated Network.

We don’t know how this study was received or what further discussions it might have prompted. It is clear that the decision was made not to act on it, with the prohibition on any foreign sales of the F-22 still in place today. After the last Raptor was delivered in 2012, the production line subsequently closed down and the tooling went into storage. The far-more-exportable F-35 remains in production and continues to find new customers abroad, something that was undoubtedly one of the many factors that led the U.S. government to pass on the possibility of an FMS Raptor.

You can find a full copy of the F-22 export study here.

There have been discussions since then about restarting the production line to make more jets for the Air Force, as well as potentially for export. The War Zone itself has touched on how the operational security concerns have likely diminished in the intervening years. The Air Force’s most recent serious look into rebooting F-22 production, at least that we know of now, came in 2017 when it reexamined the issue for Congress. That study estimated, at that time, it would cost $50.3 billion, or around $56 billion in 2021 dollars, to restart Raptor production and build 194 new aircraft.

At the same time, every country that is known to have expressed interest in potentially buying F-22s – Japan, Israel, and Australia – has now purchased F-35s. There were reports in 2018 that Lockheed Martin had pitched a hybrid design of some kind that would have incorporated elements of the F-22 and the F-35 to Japan, but no further information about any such aircraft has since materialized.

The U.S. Air Force itself is now actively planning for a future without the F-22, with its attention shifting to new manned and unmanned combat aircraft that it hopes to develop through its Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. Advanced unmanned capabilities, in particular, have come to the forefront of planning for what future aerial combat will look like, not just throughout the U.S. military, but also elsewhere around the world.

Beyond all that, it is important to remember that development of what became the F-22 began in the 1980s, before being refined in the 1990s. The Raptor has been in service for 16 years now and technology, as well as what is understood to be required for air supremacy in future conflicts, has continued to evolve. There are increasing premiums on range, payload capacity, and overall adaptability to multiple mission sets, none of which are the F-22’s strengths. All told, discussions about restarting Raptor production for any reason, especially for export, look to be increasingly moot.

After the Air Force finally retires its F-22 fleet there could be a possibility that one of America’s allies or partners might seek to buy them and return them to service. This, however, seems very remote, especially given the relatively small number of available Raptors, a total that has shrunk over the years due to accidents.

The ever-growing costs and complexities associated with operating and maintaining these aircraft might also further dissuade any potential second-hand operator. Last year, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report that said it cost the U.S. Air Force, on average, around $14 million in 2018 dollars, or just over $15 million in today’s dollars, annually, per aircraft, to operate and maintain the F-22. The cost per flight hour to fly the Raptor is around $50,000.

The U.S. government is much more likely to try to steer allies and partners toward the F-35, though some members of Congress are looking to put new restrictions on that, as well. At the same time, the 2010 export study could well be among the historical case studies the United States uses in considering the export potential of any future advanced aircraft.

No matter what, these new details about what the Air Force thought it would take to create an F-22 derivative that could be more readily exported is another fascinating addition to the history of the Raptor.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com