The impacts of the Pentagon’s short-sighted decision to stop buying F-22 Raptor stealth fighters after the production of just 195 examples have long been visible in the high costs to operate and maintain the jets and historically low readiness rates across the relatively small fleet. All of this limits how much the Air Force can get out of what is arguably its most capable air-to-air aerial combat platform. While the idea of building more Raptors is off the table, the service is hoping that radical changes to how it trains its fighter pilots will free up more of these planes for combat missions or use as high-end “red air” aggressors.

Air Force General Mike Holmes, head of Air Combat Command, which oversees the bulk of the service’s active-duty fighter jet fleets, outlined what Project Reforge, a potentially revolutionary pilot training concept he has been at the forefront of developing, could mean for the F-22s, on June 22, 2020. Holmes offered the details during a video conference the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute hosted as part of its Aerospace Nation talk series.

“Part of what we’re trying to do is see if we could create more capacity without spending more money,” Holmes explained. “We can take some of that training-coded iron and turn it into combat-coded iron. We already paid for it, we already paid for the people that fly it.”

Project Reforge, which Holmes first laid out publicly himself in a 2019 op-ed for War On The Rocks, aims to fundamentally up-end Air Force fighter pilot training, and potentially pilot training in general. Among the most radical changes would be the possibility of effectively eliminating Formal Training Units (FTU), which serve as the last step for a student pilot before they go to an operational squadron.

Right now, future fight pilots go from a phase called Introduction to Fighter Fundamentals, or IFF, to an FTU, and then to their assigned operational unit. Under the Project Reforge plan, T-7A Red Hawk jet trainers, previously known as the T-X, might be assigned to the bases with operational fighter jet squadrons. Instead of going to an FTU, student pilots could then complete the last part of their training in the T-7A before effectively walking across the ramp to join an operational squadron, whether it be one operating the F-22 or some other type.

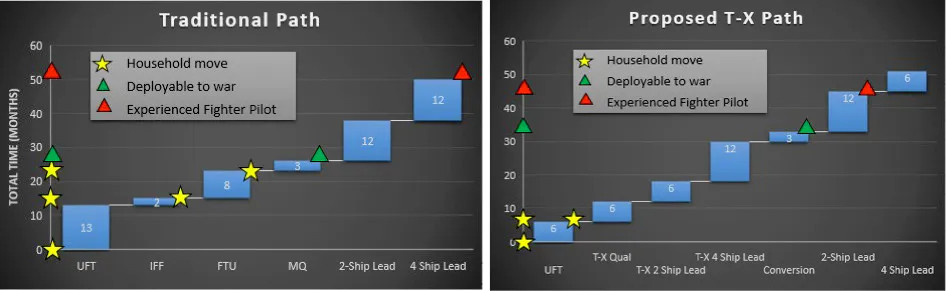

The Air Force hopes that the final version of this concept, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, could trim back to the total time it takes to prepare new fighter pilots from the 40 months it takes at present down to as little as 22 months. Getting rid of the need for the FTUs, or even just substantially reducing the number of training sorties they need to support, also means the Air Force could use the aircraft assigned to those units for other purposes.

David Timm, a contractor on the ACC staff who has also been heavily involved in Project Reforge, told Air Force Magazine for a piece it published last week that between 60 and 70 percent of sorties that the 43rd Fighter Squadron, the F-22 FTU, is performing now have to do with teaching relatively basic skills. “Teaching those skills sooner, with an advanced trainer [such as the T-7], you’re able to save 50 percent of the training days; or 60 percent of the F-22 sorties that we allocate for training in an FTU, and squadrons can use that money to focus on combat training,” he explained.

Freeing up any aircraft types for other duties, or even more specialized training, through Project Reforge could be beneficial across the board, but it would be especially so for small fleets, such as the F-22s. At present, the Air Force only has 185 Raptors, in total, following a crash in May, around 125 of which are assigned to combat-coded units. The remaining 60 aircraft are assigned to training and test and evaluation units.

As of 2017, the 43rd Fighter Squadron had around 31 jets. If the Air Force could reassign those jets to operational squadrons, or even create an additional operational squadron, it would grow the total number of combat-coded Raptors by nearly 25 percent effectively overnight.

Even if there was a need to keep some F-22s dedicated to pilot training activities, freeing up any additional aircraft could be a boon to the fleet overall. Holmes highlighted how the Raptors’ readiness rates increased when the service made the decision to consolidate its previous six operational squadrons, each with between 18 and 21 jets, into just five, each with 24 fighters.

The Government Accountability Office, a Congressional watchdog, recommended doing just this in order to realize “maintenance efficiencies because people, equipment, and parts can be shared” in 2018. After Hurricane Michael devastated Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida, then the Air Force’s main F-22 base, later that year, the Air Force had an additional impetus to implement that plan.

Holmes did note that there could be hurdles to transitioning training aircraft, which are generally older models that lack many recent upgrades, to operational units. He said that ACC asks “every year” to upgrade all of the aircraft to the latest standard, but that the Air Force’s top leadership declines in favor of other priorities. It’s possible that, if Project Reforge works, it would become more of a priority to update these jets.

This could be an extremely costly proposition, but it might be offset by the added capability these fully modernized jets would offer. Having the full fleet in the latest configuration also increase available F-22 combat capacity during a major crisis or contingency, even if subtantial numbers of Raptors remained assigned to training or test and evaluation units.

“The older-block F-22s, they’re already combat capable, even without bringing them up to the higher standard,” he added. “I’d certainly pick one of those over some of our legacy airplanes if I had to go fight.”

At the same time, Holmes said the Air Force could also look to consolidate its oldest Raptors and use them as advanced “red air” aggressors, something F-22s already do on a more limited basis. Even if there is a need to retain the FTU in at least some form, the reduction in the total number of necessary general training sorties could allow the service to devote more Raptor flight hours to this purpose.

“With the two operational squadrons here [at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia], and the red air requirements for them and the red air requirements for the FTU, [we’re asking], Can we kind of trade airplanes among each other and make an effective use of the older airplanes in a red air role while we save our limited modernization dollars for … newer airplanes?'” Holmes explained.

While older aircraft can adequately simulate a variety of existing threats, there will only be an increasing need for more advanced aggressors for Air Force fighter pilots to practice against as potential opponents, such as Russia and China, field their own stealthy and otherwise advanced combat jets. The service has already announced plans to shift some of its oldest F-35As into a new aggressor squadron to meet this growing demand.

All of this is, of course, predicated on Project Reforge delivering the promised results. During his talk, Holmes acknowledged that the Air Force would have to experiment and refine the concept before it could ever be implemented on a wide scale. At the same time, the T-7 trainers that could support the new training plan are still some time away from entering service. There is also been talk about how derivative of that aircraft, notionally referred to as the F/T-7 or TF-7, might be necessary to provide suitably advanced capabilities in the final stages of the training regimen. The Air Force is also looking at other roles for the T-7, or derivatives thereof, including employing them as aggressors.

ACC had looked at leasing a fleet of between four and eight South Korean KAI T-50 Golden Eagle advanced jet trainer aircraft by way of a sole-source contract to Texas-based Hillwood Aviation as a way to get experimenting with Project Reforge sooner rather than later. The command has now decided to hold an open competition, a process that will take longer to complete, to find a suitable fleet of jet trainers.

No matter how it proceeds now, if the Air Force can make Project Reforge work, it could revolutionize how the service trains its pilots, in general, and provide a host of other second-order benefits, especially for its F-22 fleet.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com