Happy birthday America! As we all celebrate July 4th in various ways today, it’s important to remember that our nation’s independence came at a high human cost on all sides. We wouldn’t be celebrating Independence Day without the sacrifices of colonists, tens of thousands of whom gave their lives in securing America’s independence from the British. Like any major conflict, the Revolutionary War was a testing ground for all manner of new weaponry and techniques designed to inflict heavy losses on enemy forces.

Recent advances in gunpowder meant that militia members and soldiers alike encountered massive new weapons in the field that would have seemed like dark magic to Colonial soldiers or militiamen who were serving in the armed forces for the first time and had not yet witnessed modern warfare firsthand. Crude forms of artillery had been used in Asia and Europe for a few hundred years, but the types of Napoleonic artillery unleashed during the Revolutionary War were capable of new feats of accuracy and lethality that previous designs couldn’t match. These truly revolutionary artillery weapons fell under three main categories: cannon, mortars, and howitzers.

Cannon

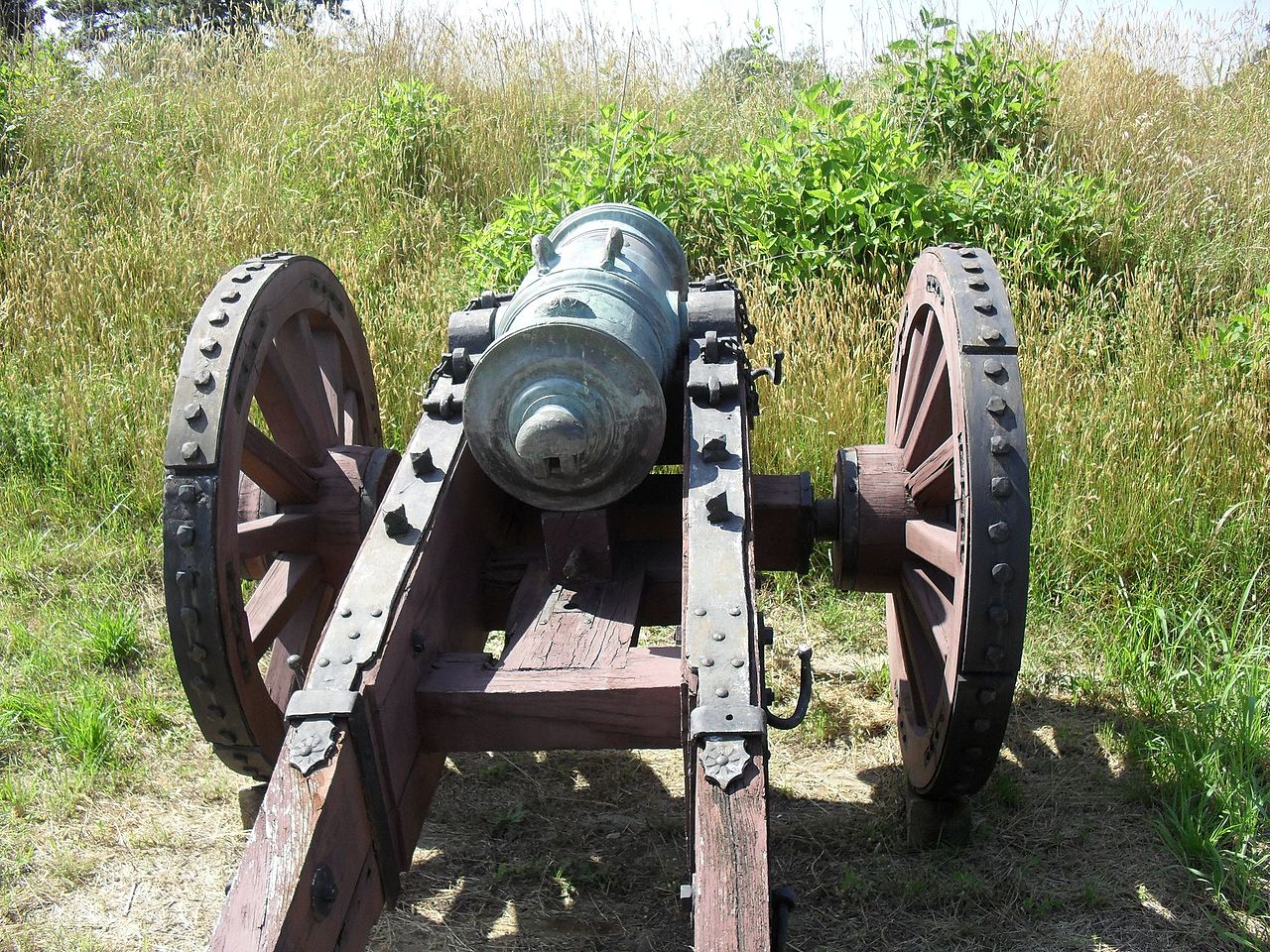

Some archaeological evidence suggests that cannon were used as early as the 12th century by the Song Dynasty in China and parts of the Islamic World, although these early examples were crude, handheld devices which more resembled vases than the long-barreled cannon we think of today. Both handheld and mounted cannon designs continued to refine and develop around the world throughout the Medieval and Early Modern Periods, leading to the smoothbore, muzzle-loading cannon which saw use on both sides of the Revolutionary War battlefield.

These cannon were typically made of cast iron or occasionally bronze, and were loaded with a pre-made paper or cloth cartridge filled with gunpowder. Cannon were typically carried between battlefields by horse-drawn carriages and were mounted on a single two-wheeled axle or sometimes a four-wheeled cart which allowed them to be moved short distances and positioned by small crews. Effective range varied wildly among different Revolutionary War cannon, but typically maxed out around 1,000 yards.

Cannon are typically rated by the weight of their projectiles. The most commonly used cannon during the Revolutionary War were 3-pound “galloper” and the steadier 6-pound guns, although larger cannon up to 18 pounds saw use in some conflicts. The recoil from these guns would propel the cannon backward, further increasing the time it would take to reload and reset each gun. Typical artillery pieces with a crew of around ten men could fire cannon at an average of four times per minute. They fired a variety of projectiles including solid shot, explosive-filled cannon balls, large diameter grapeshot, smaller diameter cannister shot, various shrapnel shells, and chain shot.

Chain shot and its more rigid variation, bar shot, consisted of two halves of a split cannon ball joined by either a chain or a solid metal bar. When fired, the two halves would spread open in flight and tumble or spin end-over-end, leaving a devastating path of destruction in its wildly inaccurate wake.

These kinetic projectiles were sometimes used as anti-personnel weapons of the most brutal kind, but were most often fired during naval warfare to snap the masts or sever the rigging of ships when fired by smaller Naval cannon variants like the carronade or the swivel gun.

Mortars

After cannon, mortars were the next most commonly used artillery during the Revolutionary War. The principle behind both weapons is the same, but mortars feature a much shorter barrel and a higher angle of fire. Like the mortar weapons of today, these were mounted on a flatbed or frame and were fired at steep angles in order to fly easily over earthworks or other fortifications and rain down shrapnel on enemies. The maximum range for these mortars was somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,400 yards, although their effectiveness dropped sharply at around 700 yards.

Typical Revolutionary War mortars featured explosive shells ranging from four to 13 inches in diameter which were loaded directly into the barrel. Unlike cannon, however, these mortars were chambered, meaning the explosive charge was loaded into a separate chamber rather than in the muzzle along with the shell.

Howitzers

Another Revolutionary War variant of the cannon was the howitzer, whose barrels were much shorter in length but much larger in diameter than the cannon. In some ways, the Revolutionary War howitzer was a hybrid between the mortar and the cannon in terms of barrel size and length. Howitzers averaged around eight and 13 inches in diameter and around three feet in length. The typical effective range of these weapons was around 750 yards.

These chambered guns also fired explosive powder-filled shells with a timed fuse that was lit by the firing charge, and were much more maneuverable during battle thanks to their shorter barrel length.

Revolutionary War Artillery Tactics

These artillery weapons played a key role in the battlefield tactics of the Revolutionary War, but their effectiveness was limited by the time it took to load and fire them and their low-level of mobility. Because these weapons were so cumbersome, officers on both sides of the conflict would have to carefully place their artillery like chess pieces before a battle in an attempt to maximize their effectiveness. Errors in planning could, therefore, render these weapons useless during a battle.

Battlefield commanders had to make careful considerations about how to use their precious artillery. Enemy infantry could be targeted in order to inflict heavy losses, or enemy artillery could be targeted in order to protect one’s own infantry. Because these weapons were so hard to move, artillery would often change hands throughout a battle as infantry advanced and took ground. Enemy artillery was seen as something of a spoil of war and both sides routinely lost and gained artillery pieces throughout the conflict.

Artillery was most commonly placed in a single group called a grand battery in the center of an infantry line, but sometimes lined flanks or were spread at intervals among infantry lines. This artillery would lay down covering or destructive fire as enemy infantry advanced, altering their type of munition depending on battlefield conditions and tactics being employed.

When enemy soldiers were densely packed, solid shot was most often fired, aimed low in order to roll or skip across the ground and mow down entire columns of troops. One anecdote claims that 42 men were cut down by a single ball during a battle and there are dozens of accounts of cannonballs ripping limbs right off of infantrymen. Explosive shells or various types of small-diameter shot were more commonly used against stationary or fortified targets such as during the Siege of Yorktown or Battle of Trenton—some of the most pivotal victories for the Continental Army.

In terms of naval artillery tactics, the Siege of Yorktown was in many ways made possible due to the fact that French naval forces possessed heavier cannon which allowed them to fire heavier projectiles at the British. Both the British and the French fleets suffered heavy losses at the Battle of the Chesapeake, forcing the British Navy to retreat back to New York without reinforcing and resupplying their forces at Yorktown with fresh artillery.

In 1776, John Adams famously wrote a letter to his wife Abigail remaking that America’s Independence Day “ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations from one End of this continent to the other from this time forward forever more.” When you’re safely and responsibly celebrating with your own mortars and explosives this 4th of July, remember the sacrifices of the brave men and women who marched into battle against the British facing the devastating artillery of the era and the many generations of servicemembers who have done so against ever-more more powerful artillery in the centuries since.