It’s nearly July 4th, happy birthday America! As we all celebrate Independence Day in our own ways, it’s important to remember the brave men and women who made immense sacrifices during the American Revolution. Like in any conflict, soldiers fighting for American independence saw their share of hardships and horrors. The Revolutionary War in many ways was a testing ground for a variety of new heavy weaponry, small arms, and even naval mines that would lead to new levels of destruction and change warfare forever. Aside from these advances in weapons, it also brought about another major sea change in terms of how armies wage war: the reliance on preserved foods that could be carried by soldiers and last for extended periods of time. One of the many firsts the war for American independence brought about was U.S. soldier ration requirements, established by a Congressional Resolution in 1775.

In some ways, the American Revolution can be seen as the birthplace of modern MREs. George Washington, the first President of the United States and the General who led the Continental Army to victory, wrote an order in 1776 declaring each man should carry two days’ worth of provisions upon hand. While these foods were most often flavorless, preserved staples that were difficult to stomach, they nonetheless were vital in keeping Continental soldiers fueled for battle.

In An Edible History of Humanity, Tom Standage writes that “For most of human history, food was literally the fuel of war.” Before the advent of industrialized food production and modern food preservation, many wars were won or lost based on which force could keep its soldiers fed. “Logistical considerations alone do not determine the outcome of military conflicts,” Standage writes in the book, “but unless an army is properly fed, it cannot get to the battlefield in the first place.”

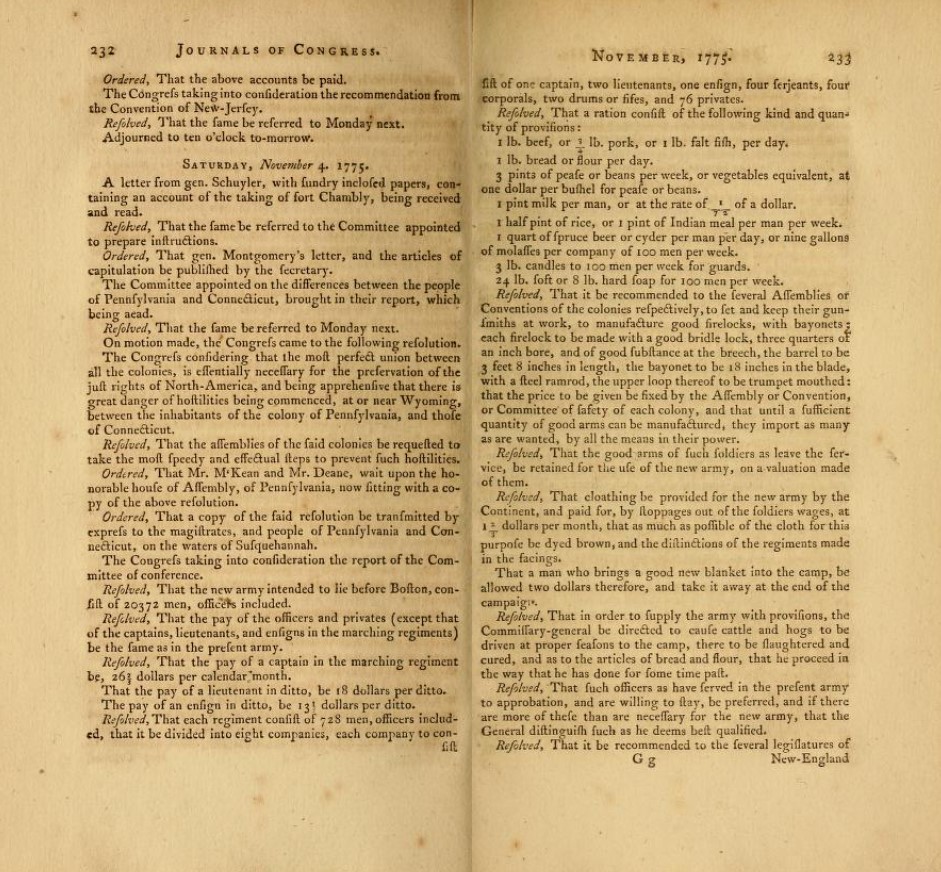

The American Revolutionary War was no different. Continental Army leaders made plans to keep soldiers adequately fed in the field, but of course, best-laid plans often go awry. According to Defense Logistics Agency historians, the Continental Congress made attempts to ensure troops were given “simple but portable and shelf-stable fare” at the beginning of the conflict with Great Britain. In 1775, the Continental Congress wrote a resolution declaring that daily rations for each soldier would be:

1 lb. of beef, or 3/4 lb. pork, or 1 lb. salt fish, per day.

1 lb. of bread or flour per day.

3 pints of peas, or beans per week, or vegetables equivalent, at one dollar per bushel for peas or beans.

1 pint of milk per man per day, or at the rate of 1/72 of a dollar.

1 half pint of Rice, or 1 pint of Indian meal [corn meal] per man per week.

1 quart of spruce beer or cyder per man per day, or nine gallons of Molasses per company of 100 men per week.

3 lb. candles to 100 Men per week for guards.

24 lb. of soft or 8 lb. of hard soap for 100 men per week.

These plans sound decadent in comparison to what troops would later encounter in the field as the war raged on and supplies ran scarce. There were plenty of times when these weren’t available. Vegetables were especially difficult to come by, so much so that soldiers were given a ration of vinegar in an attempt to ward off scurvy.

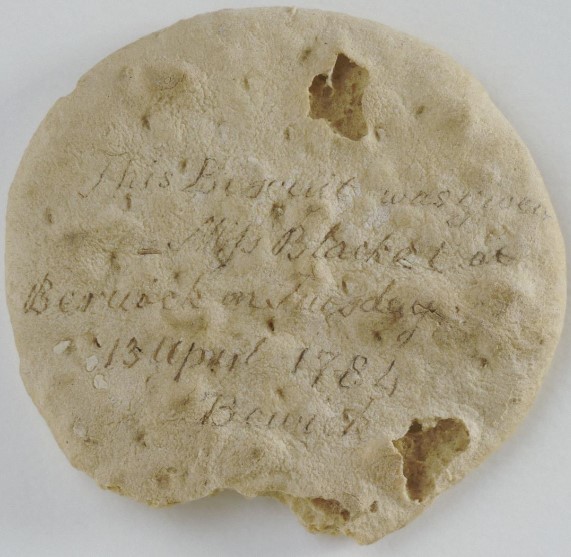

In situations when rations were scarce, which was more often than not, many Continental Army soldiers had to resort to subsisting on what was known as biscuit, fire cake, or hardtack. This simple flour and water dough was baked into hard, flavorless cakes that were often so dry that soldiers had to soak each bite in water, broth, or tea in order to eat it. If Continental soldiers were lucky, the mixture wouldn’t be absolutely ridden with insects. They often weren’t.

Writing in the journal Military Collector & Historian, author John Rees notes that “For troops on the move, commanders preferred biscuit and salt meats; especially in warm weather when they needed to issue several days rations at one time and there were inherent food spoilage problems.” The need to have ready-to-eat rations on hand was underscored by General George Washington, who wrote on September 2, 1776 that “the commanding Officers of Corps will never, in future, suffer their men to have less than two days provisions, always upon hand, ready for any emergency – If hard Bread cannot be had, Flour must be drawn, and the men must bake it into bread, or use it otherwise in the most agreeable manner they can.”

One soldier’s account states that his rations consisted mostly of “mostly corned beef and hard bread,” which could be “hard enough to break the teeth of a rat.” A German Hessian soldier fighting in the Revolutionary War on behalf of the British wrote that he “received biscuit instead of bread for entire years,” eventually becoming so used to it that he eventually “preferred biscuit to bread.”

Pennsylvania Fifer Samuel Dewees of the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment wrote an account of what Continental soldiers’ ate during the war, including how biscuit was often made of “shipstuff,” the lowest quality flour available:

Sometimes we had one biscuit and a herring per day, and often neither the one nor the other. Sometimes we had neither the one nor the other for two days at a time, and in one or two instances nothing until the evening of the third day. This was previous to our drawing a biscuit and a herring each day, the biscuit was made of shipstuff and they were so hard that a hammer or a substitute therefore was requisite to break them. This, or throw them to soak in boiling water, upon these, a biscuit and a herring each day, the soldiers lived until their mouths broke out with scabs, and their throats became as sore and raw as a piece of uncooked meat.

A recipe for biscuit from 1815 describes the process for making the semi-edible dough as follows:

BISCUIT, Sea, is a sort of bread much dried, to make it keep for the use of the navy, and is good for a whole year after it is baked. The process of biscuit-making for the navy is simple and ingenious, and is nearly as follows: A large lump of dough, consisting merely of flower and water, is mixed up together, and placed exactly in the centre of a raised platform, where a man sits upon a machine, called a horse, and literally rides up and down throughout its whole circular direction, till the dough is equally indented, and this is repeated till the dough is sufficiently kneaded. In this state it is handed over to a second workman, who, with a large knife, puts it in a proper state for the use of those bakers who more immediately attend the oven.

Adequate food supplies were most difficult to come by during the brutal winter that spanned from late 1777 to mid-1778 when General George Washington and his men were encamped at Valley Forge. During this time, food was so scarce that many of Washington’s soldiers threatened mutiny, and were known to chant “No bread, no meat, no soldier.” Like in many conflicts throughout history, the Continental Army resorted to foraging when food was difficult to come by, or worse, pillaging or theft. Officers often turned a blind eye to their troops raiding colonial settlements for sustenance.

British forces likewise struggled to keep their troops fed, compounded by their requirement to keep their Army supplied from across the Atlantic. In Major Eric A. McCoy’s article “The Impact of Logistics on the British Defeat in the Revolutionary War” published in Army Sustainment

Magazine, McCoy writes that “the problems of supplying the army from Great Britain were great, and the most serious challenge was that of shipping food over such a tremendous distance.”

This reliance on imported foods and supplies proved to be a compounding factor in Britain’s defeat during the American Revolution. “In theory, the British should easily have been able to put down the rebellion among their American colonists,” Tom Standage claims in An Edible History of Humanity. “Britain was the greatest military and naval power of its day, presiding over a vast empire. In practice, however, supplying an army of tens of thousands of men operating some three thousand miles away posed enormous difficulties. […] The British failure to provide adequate food supplies to its troops was not the only cause of its defeat, and of America’s subsequent independence. But it was a very significant one.”

It wasn’t just shipping challenges that hindered the British food supply, however. The American colonies hired private citizens to engage in piracy, an act known at the time as “privateering.” These civilian ships were authorized to harass or capture British ships, seizing their cargo and selling it back to the colonies. Writing in Army Sustainment, McCoy outlines the losses these privateers were able to inflict on British supply lines:

American privateers authorized to intercept British cargo also took their toll. Only 13 of the convoy’s ships eventually made it to Boston, and very little of their cargo survived. Only the preserved food (such as sauerkraut, vinegar, and porter) arrived intact. Most of the other provisions were rotten, damaged, or dead; only 148 of the livestock survived. Out of 856 horses shipped, only 532 survived the voyage. This convoy marked the last time that Britain attempted to ship fresh food and livestock to its army.

When supplies ran low, British forces resorted to foraging. This exposed many Redcoats to ambushes and other guerilla tactics carried out by Colonial forces, and McCoy notes that “British losses in these types of skirmishes soon equaled those suffered in larger pitched battles.”

Fast forward to today, and rations have come a long way. While modern MREs (Meal, Ready to Eat) earn nicknames such as “Meals Rejected by Everyone,” “Meals Rarely Edible” or variations of digestive euphemisms like “Meals Refusing to Exit,” these rations are nonetheless a massive improvement on the salted, dried meats and semi-edible hardtack carried by the soldiers of the Revolution.

That’s not to say hardtack has completely gone away. The simple, shelf-stable “bread” is still a common item for survival kits used in maritime operations or even by long-distance backpackers. Hardtack can still be found in some MRE kits around the world today.

The role that food supplies played in the American Revolutionary War underscores the fact that wars aren’t always won by weaponry and tactics alone. Logistical concerns like how to ensure soldiers are properly fed in the field take just as much precedence as combat supremacy does. General George Washington and the Continental Congress saw this need for soldiers to have ready-to-eat foods with a long shelf life 225 years ago, paving the way for modern MRE delights such as the reviled Chicken a la King or the infamous Veggie “vomelet” Omelette.

This Independence Day, as you’re firing up the grill and cracking a cold one, remember the culinary sacrifices made not just by the Continental Army, but by all U.S. troops in the field. If you really want to honor their sacrifice, maybe even consider adding some hardtack to your menu.

Bon appétit!

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com