Nestled to the south of Vandenberg Air Force Base’s massive 15,000-foot runway and connected to it by a long, private taxiway sits a peculiar facility encased inside two layers of security fencing, with its entrance from the taxiway only accessible via a pair of sliding gates. At first glance, its appearance is reminiscent of a high-security prison, but this facility is meant to keep people out, not keep them in. But the origins of this highly peculiar installation are far higher-profile in nature than whatever its mission is now.

Years ago, I wrote a feature on Vandenberg Air Force Base’s Space Launch Complex Six (SLC-6) very colorful, but not widely known past. It was built to launch the Air Force’s own Space Shuttle and was a far cry from the expansive Apollo-inherited infrastructure NASA’s Space Shuttles operated from at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Instead, SLC-6 was a remarkably compact facility tucked between the California coastline and the Santa Ynez mountain range. To put it simply, it looked like something right out of a James Bond movie, not reality.

Part of the infrastructure needed for the USAF’s Space Shuttle program beyond SLC-6 was an Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF). A critical piece of the Shuttle’s operation, the OPF was a highly customized hangar facility designed to regenerate the Orbiter after each mission. Originally, this was supposed to include a fairly abbreviated process, allowing for continuous access to orbit on the cheap, but as the Shuttle program progressed, this operations model—and the business case that supported it—dematerialized, with the Orbiters having to go through a months-long and very expensive process of rehabilitation after each use.

Regardless, the USAF needed its own OPF at Vandenberg for independent operations. From what we can tell, the base’s OPF was built in a very logical place, just south of the runway that would recover the Shuttle after most missions and where the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft would ferry the Orbiter to when landings at another runway were necessary. With a long private taxiway accessing the end of Vandenberg’s runway, the Orbiter could be towed back to the OPF with ease, where it would be turned around for the next mission. It would then be towed to SLC-6, located 10 miles to the south, for mating with its fuel tank, boosters, and payload before launch.

The thing is, none of this ever happened. By the mid-1980s, the Space Shuttle was already proving to be a far more resource-intensive capability than what was originally envisioned. Once the Challenger blew up during ascent, the Air Force canned its Space Shuttle dreams and moved to invest in other ways to access space as it needed, some of which may have been quite experimental and exotic in nature.

In the years that followed, SLC-6 was repurposed, although without success, until it found the right fit in the mid-2000s, as I described when I wrote about SLC-6 in 2015:

After the cancellation of the Defense Department’s arm of the Shuttle Program, SLC-6 was used by multiple defense contractors with varying results (see a full launch list here). By the early 2000s, a legend that the complex was badly cursed had grown to massive proportions, as so many billions of dollars had been poured into the installation, under the guise of a whole slew of programs, with very little to show for it in the end.

Finally, in the mid-2000s, Boeing took over the facility and re-utilized much of the Shuttle’s infrastructure for their Delta IV rocket program. The first Delta IV Medium rocket was triumphantly launched from the long-beleaguered complex in 2006. Since then, the once doomed SLC-6 has performed extremely well launching large payloads into space, most of which contain America’s most high-tech and secretive space-based spying technologies. This is somewhat of an ironic reprieve for the site as it had unsuccessfully been envisioned as facilitating just that mission for close to half a century.

While we know all about the history of SLC-6 and how it eventually found success after decades of uncertainty, the Orbiter Processing Facility at Vandenberg is something of an information black hole. I wanted to follow-up on my popular SLC-6 story with a feature about the geographically separated OPF’s own history and what it is up to now, but there was little to no information of any about it. This seemed very odd for something of such historic significance and that is quite large and elaborate and situated on a fairly high-profile Air Force installation.

There is nothing secretive about the OPFs at Kennedy Space Center, which has three of them arranged near the gigantic Vehicle Assembly Building. After the Space Shuttle program was shuttered, those facilities have been given a whole new life. Two are leased by Boeing to support the USAF’s X-37B miniature spaceplane program. The other is also leased by Boeing, but is used for their CST-100 Starliner capsule program. Yet when it comes to Vandenberg’s OPF, the tenant is completely unknown. In fact, it seems as if it was never disclosed in the decades that followed the abortive military Space Shuttle program.

Check out just how elaborate, large, and advanced the OPFs are:

Vandenberg AFB seems to be quite open when it comes to its various tenants and uses for its launch facilities. There are multiple rocket assembly buildings scattered all around the base used for a number of customers and programs, but nothing as expansive as the OPF. With this in mind, I reached out to the base’s public affairs shop in hopes of getting a simple answer as to what the facility is used for today, or at least about its history following the collapse of the Pentagon’s Shuttle Program. It turns out, they are not willing to share any information about the facility or really even comment on its existence.

So, this leaves us with an odd mystery of sorts. Secret hangar facilities working on undisclosed projects are usually the domain of remote locales, like those in the expansive deserts of the American Southwest. But really, there is no other facility that comes to mind that is better suited with operating an incredibly advanced and clandestine aircraft that needs a lot of space to operate in.

First off, the facility is located deep within an already highly secure facility. This offers high security, but also far better accessibility compared to the remote options in the Nevada desert and elsewhere. Second, the OPF is basically the most ‘Cadillac’ of hangars ever constructed, capable of fully renovating a Space Shuttle with all its exotic materials and workshop needs. Vandenberg’s OPF is even larger than those at Kennedy Space Center. In addition, it was already built and paid for by the USAF for a program that never actually materialized.

Third, it has incredible accessibility to one of the longest runways in the United States. Whatever lives inside that hangar can taxi—or be towed—from its ultra-secure roost, out directly to the end of the runway and launch without even having to use the airfield’s shared aprons and taxiways. It can do the same in reverse for recovery. If the aircraft in question can be transported by airlifter in a disassembled state, moving it to and from its loading area on the base would also be an extremely secure and private affair.

Finally, and most importantly, Vandenberg AFB sits on the California Coast adjacent to where vast military range facilities are located. Literally, the airspace off Vandenberg is part of gargantuan range complex that extends over the Channel Islands and far out into the Pacific and down along the Baja Peninsula. This is where the Navy and the Air Force do some of their most extensive and sensitive testing, including live missile shoots and highly integrated war games.

Combined, these ranges absolutely dwarf those that exist over land, including the expansive Nellis Test and Training Range that occupies a huge chunk of Southern Nevada. In fact, from what we understand, quite a bit of testing of secretive aircraft based in the deserts of the western U.S. occurs over these over-water ranges. Being able to access them without flying over the population in itself is also a huge plus.

We also know that Vandenberg AFB does have a test function for secretive aircraft, in particular, unmanned ones. The RQ-170 program has a detachment there and the bat-winged drones fly from the base’s runways fairly regularly. We also know they use the airfield’s main ramp and hangar for their operations, not the expansive OPF.

It’s hard to stress how unique this arrangement is. Although people often think secret aircraft can be shoved in any hangar on any base, that simply is not the case. Few facilities have the ability to offer high-security and isolation, while also ease of operations and access to vast sanitized airspace like what we see at Vandenberg.

So, what lives inside the historic OPF today? We have no idea, but logic points to a number of possibilities and one’s imagination can pretty much run down the rabbit hole from there. Something capable of high speed, that would require the base’s long runway and the huge range complex that sits adjacent to it makes a lot of sense. Sonic booms, deep rumblings in the sky, and strange contrails have been present off the SoCal coast dating back to the late 1980s. In fact, those reports continue to this very day.

It’s also worth noting that the D-21/M-21 combo, a parasite drone-mothership system that is part of the A-12 Oxcart/SR-71 Blackbird family of aircraft, was tested in secrecy over this range complex as over-land alternatives were far too restrictive and problematic.

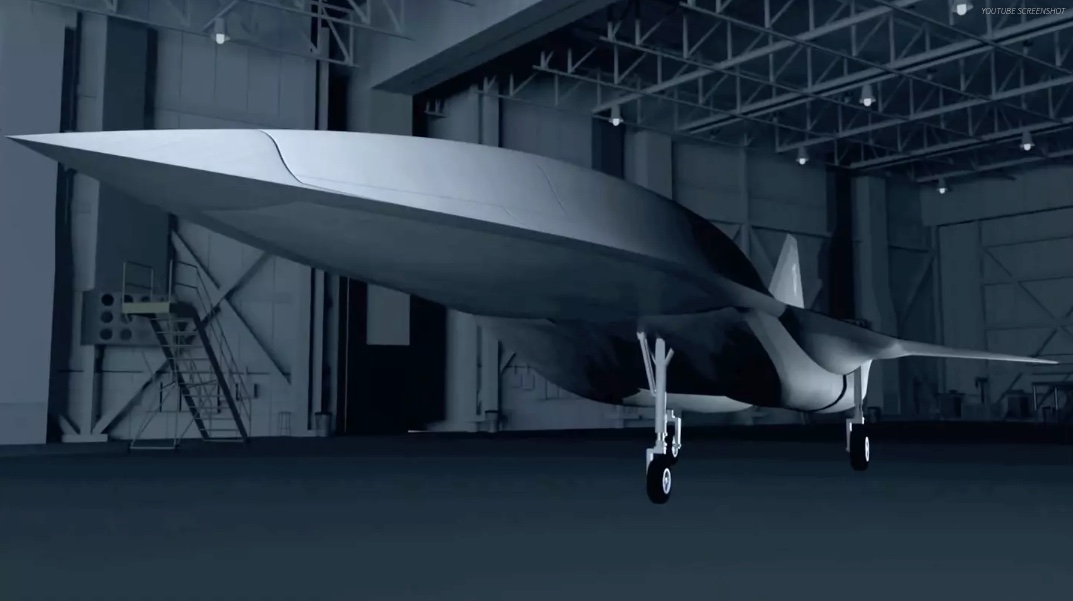

The utility of high-speed platforms has made a drastic resurgence as of late, with the Pentagon investing billions into hypersonic capabilities of many flavors. One of these is the much talked about ‘SR-72’ hypersonic unmanned strike and reconnaissance aircraft that Lockheed is working on. As I have posited in detail, it seems as if the corporate chatter we are hearing about this craft is a reflection of the past, not the present. Lockheed’s competition is also interested in getting a taste of the USAF’s high-speed reusable aircraft buck. Regardless of who owns it, the OPF would be perfectly suited to such a machine or a technology demonstrator progenitor to it.

A reusable spacecraft launched from a larger mothership that sorties from a different location, but recovers at Vandenberg is another possibility. It’s also a concept which we have delved into deeply in the past and one the USAF was interested following the collapse of the Shuttle Program. The OPF’s main bay is roughly 150 feet across as measured on Google Earth, so it’s not a like a massive aircraft could occupy the facility, but something the size of the Space Shuttle certainly isn’t small either. On the other hand, a smaller two-stage-to-orbit space-launch system capable of putting small payloads in orbit could also possibly call the OPF home.

A facility used to support a small force of experimental, autonomous, and highly networked unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) drones would also be beneficial as they could use the vast range spaces to put their capabilities to the test. The OPF’s shadowy status would certainly fit with the equally puzzling status of any kind of USAF UCAV program. You can read more about this strange reality here.

There are other, far more exotic possibilities to ponder as well, even if just for one’s imagination’s sake, one of which was actually present in the region during a notorious series of events that occurred off the Baja Coast back in 2004.

On the other hand, maybe the OPF has a far more mundane purpose. But if that’s the case, why not offer some details about it, especially considering the facility’s historic significance?

With the Space Shuttle program in America’s rear-view mirror now, its story will only become more fascinating, and a large part of it doesn’t have to do with NASA, it has to do with the Pentagon. Hopefully, we will find out what happened to Vandenberg’s abortive Orbiter Processing Facility and how it ended up influencing the future of aerospace technology sooner rather than later.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com