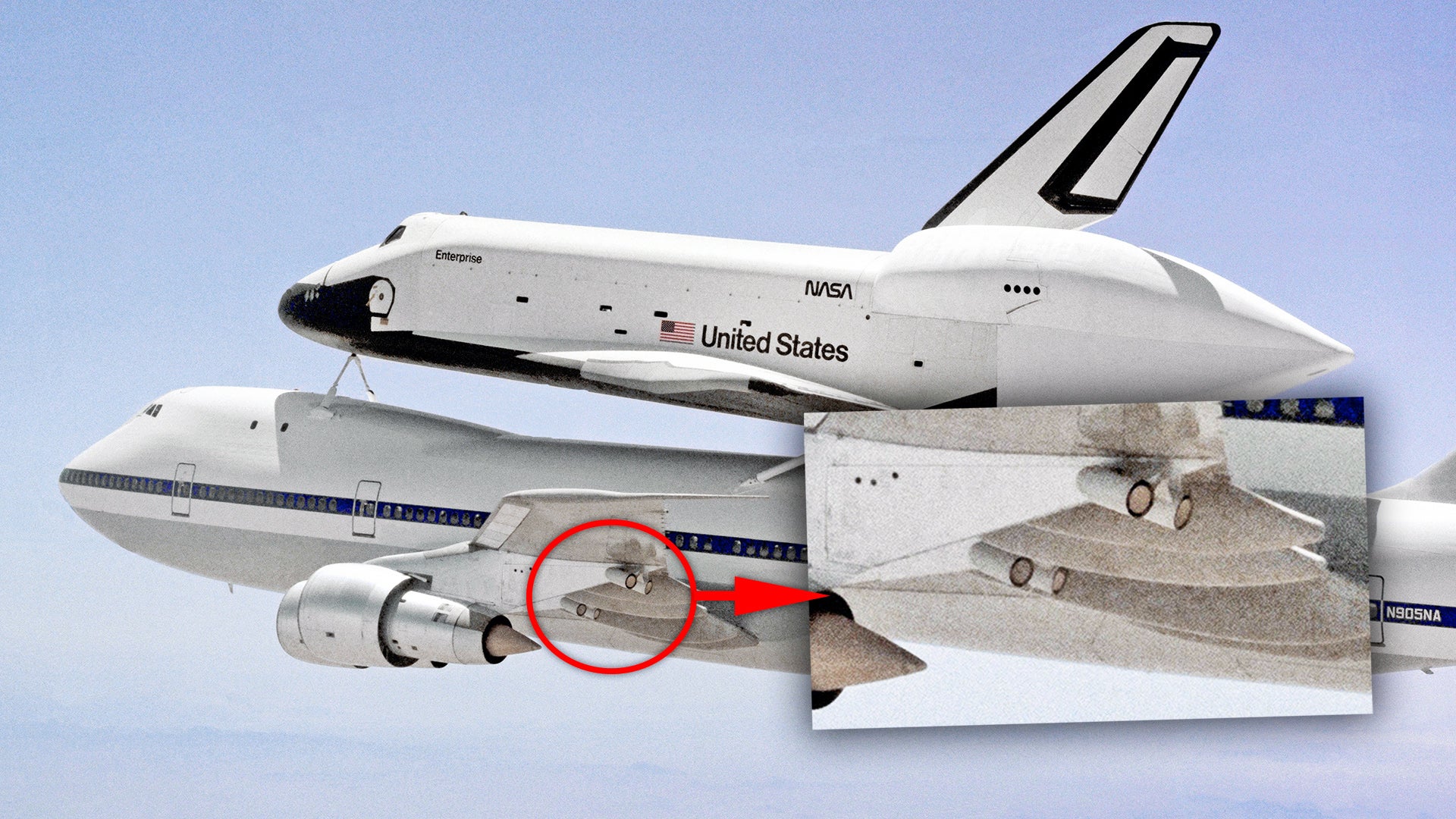

In May 1983, what was then NASA’s only Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a highly-modified Boeing 747 airliner capable of carrying a Space Shuttle on the top of its fuselage, arrived at the Paris Air Show carrying the shuttle Enterprise. The international aviation spectacle, arguably Europe’s highest-profile air show, had long been an arena for Cold War competition. While the visit was hugely publicized, what most don’t know is that the plane had been modified for its European trip with an advanced countermeasures system to protect itself from heat-seeking missiles that was still highly classified at the time. The defensive additions to NASA’s 747 were so sensitive that the plane’s crew was told to keep it a secret no matter what.

The story of exactly how NASA’s jet came to be equipped with this system is oddly murky, as are details about the specific factors that prompted this modification, considering the very high-profile and public nature of the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft’s (SCA) attendance at the 1983 Paris Air Show. It certainly was not a secret for long that this plane, which carried the U.S. civil registration code N905NA, was fitted with a countermeasures system for this trip, something that was reported on in Aviation Week after the aircraft touched down in France after spotting the mysterious modifications. The system itself appears to have been one known variously as Have Charcoal and Matador, or a related predecessor.

The War Zone reached out to NASA’s History Division for more details about the installation of this self-defense capability on this particular aircraft, which carried the U.S. civil registration code N905NA, but individuals there had no luck finding any additional information. We’ve also submitted a number of Freedom of Information Act requests related to this story.

Here’s what we’ve been able to find out so far.

NASA had first acquired N905NA in the early 1970s from American Airlines. While the plane had that company’s logos removed, it continued to fly for a time with that carrier’s basic paint job, before being repainted in a white and gray NASA scheme with a blue cheatline. This jet was heavily involved in the testing of Enterprise, the first prototype Space Shuttle, which Rockwell completed in 1976 and that conducted its first free test flight in 1977.

You can read all about the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft in this past feature of ours.

Enterprise was originally supposed to be named Constitution, but NASA changed the moniker on orders from then-President Gerald Ford who been on the receiving end of a major letter-writing campaign by fans of the sci-fi television show Star Trek. That show centered on the exploits of the crew of a spaceship called the Enterprise, as did numerous sequels and spinoffs, including a number of full-length feature movies.

Enterprise never actually went into space. It was built initially as an atmospheric test article and lacked various key features and systems for actual spaceflight. NASA had planned to make it spaceworthy after the conclusion of the testing. However, the core design of the shuttle changed dramatically during the construction of the second example, Columbia. NASA and Rockwell subsequently determined it would be easier and cheaper to make an older test article named Challenger capable of exoatmospheric operations rather than effectively rebuild Enterprise, which was ultimately relegated to various test roles.

As a result, NASA was initially unsure of exactly what it wanted to do with Enterprise following the completion of the original testing plan. One mission for the Space Shuttle that couldn’t go into space was to help promote the program on Earth, as well as NASA in general, as part of a high-profile tour of various sites in the United States and Europe in 1983. The plan as it ended up being carried out saw N905NA bring the shuttle to the following locations, in order as they are listed: Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado, McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, RAF Fairford in England, Bonn-Cologne in what was then West Germany, Le Bourget Airport in France, stops in Italy, and then finally Ottawa in Canada. On the flight to Europe, the SCA carrying Entperise made relatively brief stopovers at Goose Bay in Canada’s Newfoundland and at Naval Air Station Keflavik in Iceland.

“We overnighted at a lot of them but some we didn’t. Some of them were just a gas-and-go. Keflavik, Iceland, was a gas-and-go, but Fairford, England, was the next stop,” Pete Seidl, who worked as a site supervisor for the SCA between 1979 and 2008, recalled about the tour, which was a major undertaking, in an interview for an official NASA oral history monograph. “These people were crazy. NASA sent a whole bunch of PR stuff with us and they gave us these little pins, shuttle pins. … these pins were like gold.”

“After that we went to Bonn, Germany. We had a good time there. They really treated us nice in Bonn. They went overboard,” he continued. “Gosh, we went bar hopping that night and couldn’t buy a drink, those people were so friendly. Shots for everybody; it was a fun time but we all felt like hell the next day.”

“Then after that we made it in to Paris. In Paris we were just supposed to display the airplane. There weren’t supposed to be any flights at all in the show,” the retired SCA site supervisor explained. “Well, Joe Algranti was in charge. He was the director of operations at Houston [at the Johnson Space Center], flight operations. Anyway, he decided he wanted to fly it, so we started flying.”

“The people just loved the flights but they hated us because it was such a cramped area in the parking space where we were,” he added. “These vendors would have to move all their little tents and everything when we went by, so we were very unpopular. They got over it finally but it was pretty trying.”

At some point before all of this, the decision was made to install the infrared countermeasures system on N905NA. “Before we even went they decided that they needed a missile defense put on our aircraft, so they had a team from Boeing come out; it took them about a week and they installed an infrared missile defense,” Seidl said in his oral history interview. “It was quite a job.”

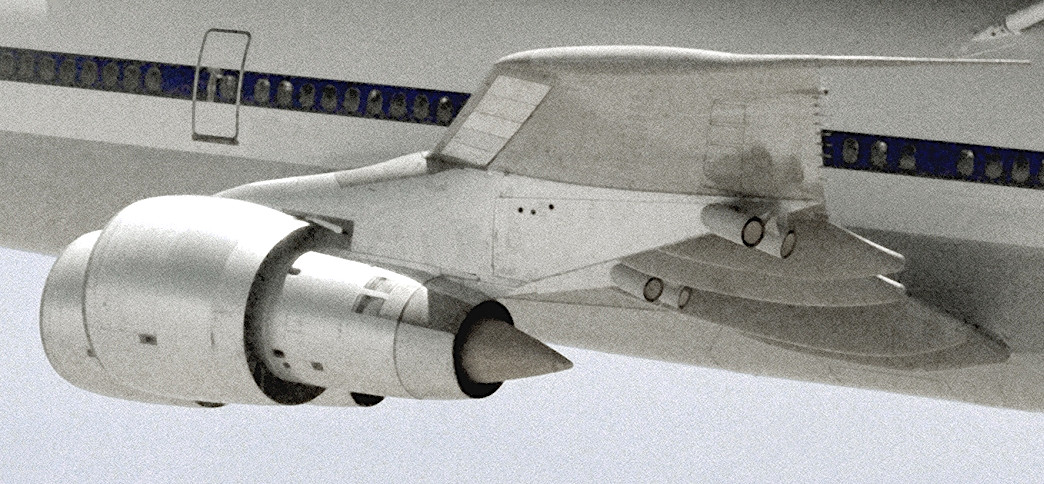

From the photographs and other information available, the countermeasures system that was fitted to N905NA appears to have been Have Charcoal/Matador, or at least a closely-related predecessor to it. This system was very new at that time, with the initial version only having been first developed for the U.S. Air Force in 1982, according to GlobalSecurity.org. Have Charcoal was the Air Force’s official nickname for the development program. Matador was the trade name for the system. The U.S. military eventually assigned the designation AN/ALQ-204 to at least some versions of the system. It’s not immediately clear who was responsible for the development of the original design, something that is often attributed to Lockheed. However, early units were built by Sanders Associates, a company well known for designing and building infrared countermeasures (IRCM) systems, which only became a Lockheed subsidiary in 1986.

All Matador variants work on the same general principle, emitting large amounts of pulsed infrared energy to blind and confuse the seekers on incoming heat-seeking missiles. This could prevent an opponent from achieving a lock to begin with or break an infrared-homing missile’s lock after it had been fired. Compared to expendable decoy flares, IRCM systems like this can provide more persistent protection, do so without the dangers and handling issues surrounding expendable flares, and are better suited for countering the latest in infrared seekers. Matador is also somewhat modular with a central control system being able to support multiple emitters positioned around an aircraft.

Whatever the exact system that was fitted to N905NA was, it had a total of eight emitters, two at the rear of each one of its four underwing engine pylons facing slightly downward. This would have provided good coverage against various contemporary air and ground-launched heat-seeking missiles in service around the world in the 1980s, many of which typically could only effectively home in on the heat plume at the rear of an aircraft’s engine exhaust.

We don’t know if there were any specific threats that prompted the decision to fit Matador to N905NA, but it is clear that terrorism was at least one factor. A number of terrorist organizations were active in Europe at the time, including but certainly not limited to militant communist-inspired groups like the Red Army Faction and various anti-Israel Arab nationalist ones.

In addition, though still a relatively new category of weapons at the time, highly-portable shoulder-fired heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, also known as Man-Portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADS) were already emerging as a serious concern for commercial flights, as well as military aircraft. A 2019 RAND Corporation report on the use of MANPADS against commercial aviation mentions two separate incidents in Italy in 1973 in which terrorists linked to a group called Black September attempted, but failed to shoot down Israeli airliners with unspecified shoulder-fired missiles. Black September is most infamously associated with the massacre of athletes from Israel at the 1972 Olympics in Munich in West Germany.

The video below is a Soviet-era training video for the 9K38 Igla MANPADS, also known to NATO as the SA-18, which entered service in the early 1980s.

Some of these terrorist groups even had ties with the Soviet Union, which might have raised additional concerns about the possibility of the Kremlin leveraging proxies to carry out some kind of attack. The Soviets had been very publicly critical of the Space Shuttle program, which they accused of being a cover for space-based weapons and intelligence-gathering systems.

Whether those specific allegations were true or not, the U.S. Air Force was certainly a major stakeholder in the Space Shuttle program and the orbiters were used to support secret U.S. military and Intelligence Community missions. In fact, before the loss of Challenger, when it was still hoped the Shuttle would make regular low-cost trips into orbit, the Air Force’s involvement in the program was extensive, with its own launch, recovery, and reset facilities constructed at Vandenberg AFB in California.

Meanwhile, the Soviets were pushing ahead with work on their own shuttle, the Buran, at the time. The Soviets would have had a vested interest in seeing the U.S. Space Shuttle program veer massively off course.

Of course, Matador would have offered less protection against some kind of more concerted or even overt attempt by the Soviets to shoot N905NA down, potentially under false pretenses. While Matador would have offered a way to neutralize heat-seeking missiles, it would not have provided any defense against radar-homing types. In September 1983, just months after the conclusion of the SCA’s tour of Europe, a Soviet Su-15 Flagon interceptor did shoot down a civilian 747, Korean Air Lines Flight 007, over the Sea of Japan with a pair of K-8 air-to-air missiles, likely one heat-seeking and one radar-homing type, as was the common practice at the time. The Soviets initially denied that the incident had occurred at all, but eventually admitted to destroying the airliner while claiming, without evidence, that it had been involved in a clandestine spy mission.

With someone providing credible intelligence as to potential threats to the SCA — who exactly that was remains unclear — it’s not hard to see how NASA wouldn’t approve a plan to equip N905NA with defensive capabilities which were cutting-edge for their time. Taking any steps necessary to avoid the possibility of losing this SCA is more relevant than it may seem as it was the only one in service at the time. Losing it, as well as Enterprise, would have massively hampered the Space Shuttle program’s, progress, which was faltering at the time, in addition to just being a highly embarrassing catastrophe. A shootdown would have had the potential to cause casualties and other collateral damage on the ground, which would only exacerbate the fallout from any such incident.

It’s also important to stress that the SCA was absolutely critical to the Space Shuttle program. Without it, the orbiters could not be moved around the country as necessary and the Air Force’s dreams — although misplaced in retrospect — of putting the system to work full-tilt would be delayed further. The SCA was truly a strategic asset although it may not have seemed like it at the time.

After that decision was made, Matador, or an experimental progenitor of it, would have been an obvious choice. The system had been designed from the outset with an eye toward being able to be fitted to various types of large aircraft, including airliners. One of the first aircraft it was installed on was a Boeing 707-based VC-137C aircraft known as SAM 27000. That aircraft had served as the Air Force’s primary Air Force One plane for transporting the President, their family, and their closest advisors around since 1972. It also had the benefit of requiring relatively little training to operate, with the crew being able to switch it on during the flight and simply have it running in the background.

At the same time, this may well help explain why the history behind the installation of Matador on N905NA remains so obscured. In 1983, information about Matador and the technology behind it, which was being used to protect the President of the United States, would have been very closely guarded. While Seidl mentions that Boeing carried out the modifications to the SCA ahead of its trip to Europe, it seems more than plausible that the Air Force would have been involved in some way, even if only to ensure proper operational security measures were taken.

In his recollections in the NASA monograph, Pete Seidl, the retired SCA site supervisor, lent some credence to this potentiality, saying:

Back then it was supposedly a secret. They told us: “don’t tell anybody, don’t tell anybody what they are.” So we kept it a secret; we were trying to. After we got to Paris Air Show all of the refuelers were asking us what those were. We had to tell them they were directional lights for in-flight refueling. We didn’t even have in-flight refueling on the airplane so that was a farce, but we went along with it. We left here and had to go way up north and across to get over there because we didn’t have very long range with the orbiter on the back, 1,500 miles I think was probably our max – pretty short legs.

After the SCA’s European tour, it was quickly demodified, as well.

“As soon as we got back they took all that off. It wasn’t on there very long,” Seidl told his interviewer. “It went by the way side. Never put it on again. Still have the hookups and everything but never had any use for it.”

Seidl’s recollections about N905NA being equipped with Matador appear to be, by far, the most detailed official statements on the matter. As already noted, NASA’s internal history office told The War Zone that it could not locate any further information on this topic. NASA also said that it could not find any relevant records in response to one of our Freedom of Information Act requests.

“The History Office also consulted the Agency shuttle expert who noted that the ALQ-204 system was still under development in 1983/84,” the FOIA office at NASA’s headquarters wrote in a letter responding to that request. “He stated that the system was not available for NASA use at that time as it was just beginning operational trials specifically for United States Air Force (USAF) use in 1983.”

Of course, whether or not Matador was the system in question, Seidl’s oral history interview, the readily available pictorial evidence, contemporary news reporting on the subject, and information found in other secondary sources make clear that infrared countermeasures were installed on the SCA. Beyond that, this statement does underscore just how sensitive the entire arrangement was at the time and continues to be for whatever reason.

Regardless, the Matador-less N905NA continued to serve as an SCA, as well as in support of other testing, for decades afterward. In 1988, it was joined by a second SCA, a modified 747 that NASA had acquired from Japan Airlines, which was assigned the U.S. civil registration code N911NA.

As was mentioned earlier in this piece, Enterprise never went into space, though NASA did consider making it spaceworthy after the Challenger disaster in 1986. It was used for various other test purposes, including to explore the causes behind the loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003.

NASA shuttered the Space Shuttle program for good in 2011 and many of N905NA’s own last flights involved ferrying retired shuttles around the United States to museums. This SCA is now itself on display with a mockup of the shuttle Independence on top at Space Center Houston, NASA’s official visitor’s center at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Various versions of Matador did find their way onto various other aircraft, including other military and commercial types, including the Air Force’s 747-based VC-25A Air Force One jets and E-3 Sentry Airborne Warning And Control System (AWACS) radar planes, as well as the earlier VC-137C aircraft that served as Air Force One, as well. The Matador installation on N905NA differs from the one seen on the later VC-25A Air Force One aircraft, which have a single multi-faceted enclosure at the rear of each engine pylon and one on the tail. Still, Boeing might have leveraged some of its experience modifying NASA’s SCA when it added the latest version of the system to those presidential jets, the first of which was delivered to the Air Force in 1990.

Various other IRCM systems had been in service across the U.S. military before the development of Matador and afterward, as well. At least one Matador variant did eventually receive a certification from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) underscoring its use in the commercial aviation industry. It was acquired for head-of-state aircraft internationally, such as on the Sultan of Brunei’s old 747 and those belonging to middle east royalty flights, like on Oman’s 747SP, and others. An installation was also designed for Gulfstream business jets.

In 1995, as part of the merger of Lockheed and Martin Marietta into Lockheed Martin, Sanders became part of Lockheed Martin Aerospace Electronic Systems. Lockheed Martin subsequently sold that division to U.K.-headquartered BAE Systems in 2000, which continued to produce Matador for some time afterward, though it no longer lists the system on its website. BAE Systems, as well as a number of other companies, continue to offer various IRCM systems, including various newer laser-based directional infrared countermeasures (DIRCM) types. These systems are designed to defeat advanced infrared-homing threats from all aspects.

The use of an IRCM system to protect NASA’s prized shuttle-carrying 747s during its 1983 visit to the Paris Air Show and other stops along the way is certainly intriguing. What started out as a technical interest for us turned into something of a Cold War mystery. The big question remains: what intelligence led to such a drastic measure being taken and who supplied that intelligence to NASA?

We hope to find out more as our investigation continues.

Update 4:25 PM EST:

After the publishing of this story, Dennis Jenkins, an expert on the Space Shuttle and author, who worked on the program directly during his 33 years as a contractor to NASA, reached out to us with more information about the infrared countermeasures system installed on N905NA. The system in question was actually an earlier design developed prior to Have Charcoal/Matador as part of a Quick Reaction Capability (QRC) project and was known as the QRC-81-01 Ten High.

The QRC-81-01 was developed as part of a program known as Have Siren and it functions in the same general manner as Matador. In addition, while Matador is often cited as the infrared countermeasures system installed on the VC-137C Air Force One aircraft, it appears that plane was actually also fitted with the QRC-81-01. This was the system used on variants of the E-3 Sentry radar plane, a number of different models of RC-135 intelligence-gathering aircraft, and certain EC-135 types, among others, as well.

Jenkins further explained that from his research it appears that N905NA delivered Challenger to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida before flying to Paine Field in Washington State on April 18, 1983. Boeing’s facility in Everett, Washington, the location of the 747 production line, is attached to Paine Field. The SCA then flew to Edwards Air Force Base on April 28. There are photographs, seen below, of the plane at the Dryden Flight Research Center, now called the Armstrong Flight Research Center, which is situated within Edwards, with the system installed as of May 16.

“There is remarkably little documentation on the installation,” Jenkins told The War Zone. “So it probably got installed at Paine. Ten days was quick.”

“The QRC was missing by the time of the [shuttle] Discovery delivery flight on 6 November 1983,” he added. “No visits to Paine in the interim, so I suspect it was removed at McConnell [Air Force Base]/Wichita [in Kansas] since she was there for most of July.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com and tyler@thedrive.com