Iran has made the rare acknowledgment that an attempt to put a satellite into orbit using a domestically produced space launch vehicle has failed. The launch was already controversial, drawing criticism from the United States, Israel, and others who accuse the Iranians of using their nascent space program as a cover for the development of advanced ballistic missiles. It also comes amid revelations that the White House asked for options for a military response to Iranian-backed militia attacks on American diplomatic facilities in Iraq last year.

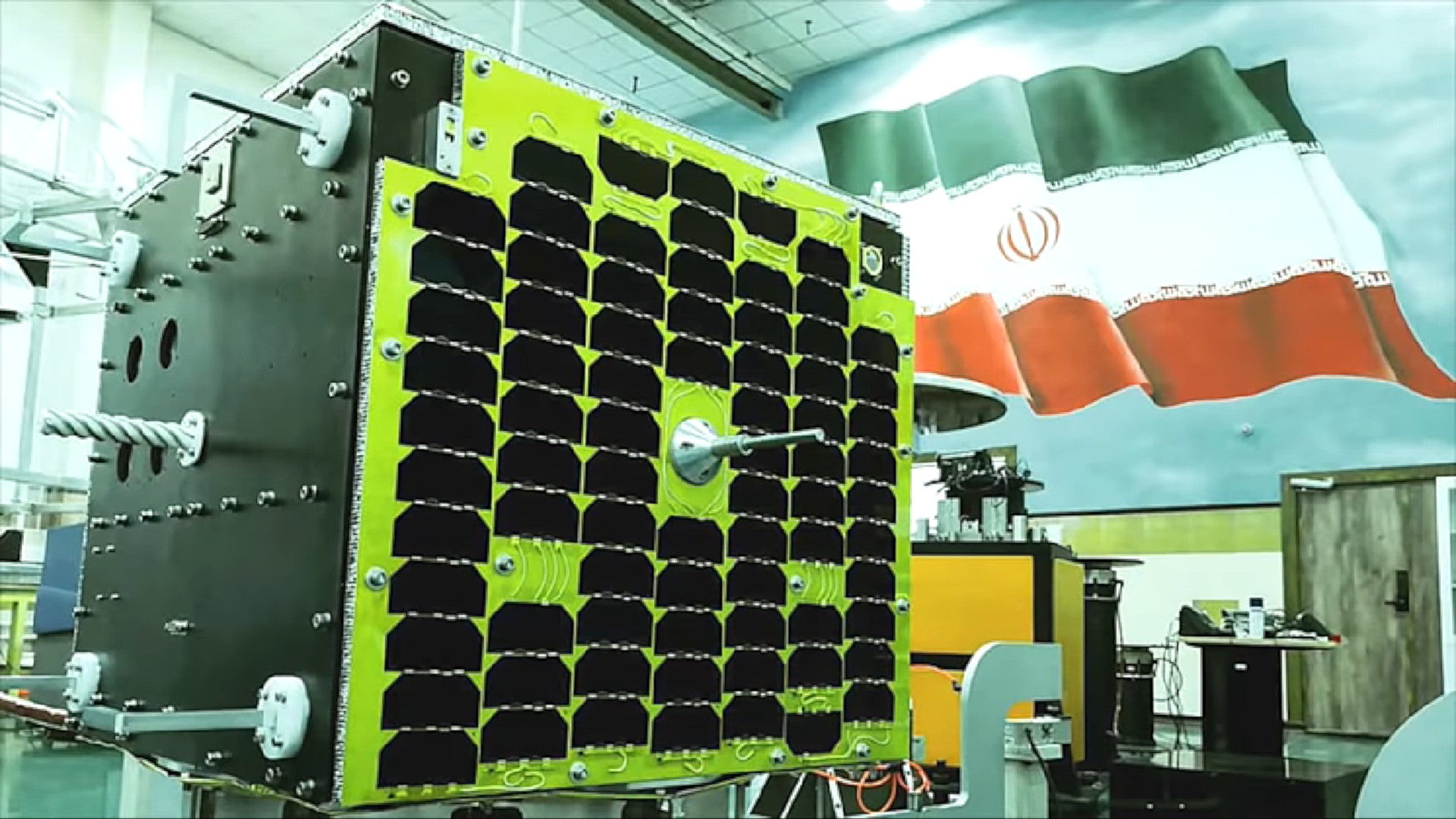

The Iranian Simorgh space launch vehicle lifted off from the country’s Imam Khomeini Space Center, also known as the Semnan Space Center, on the night of Jan. 14-15, 2019. The rocket was carrying the Payam-e Amirkabir satellite, which Iran officially described as carrying four cameras for scientific earth observation purposes from low earth orbit.

The exact nature of the failure is unclear. Iranian Minister of Communications and Information Technology Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi seemed to indicate that the satellite never even reached escape velocity, according to a report from the state-run Islamic Republic News Agency, or IRNA.

Other interviews with the minister seemed to suggest that Payam had reached outer space, but did not successfully enter a stable orbit. Azari Jahromi did say that whatever the fault was, it occurred with the third stage carrying the satellite.

It also remains to be seen when Iran might proceed with the launch of a second non-military satellite, Doosti, the mission of which is not immediately apparent. Azari Jahromi said the satellite “waiting to be launched,” according to IRNA.

So far, the Simorgh launch vehicle has yet to successfully put a satellite into orbit. Iran publicly unveiled the rocket in 2010 and conducted a successful sub-orbital test flight in 2016.

In 2017, to mark the official rebranding of Semnan as the Imam Khomeini Space Center and the expansion of the facility, Iran launched another Simorgh, possibly carrying Tooloo, an experimental intelligence satellite. That launch failed, as well, reportedly due to a problem with the second stage.

At that time, Iran said it had plans to put two communications satellites into orbit by March 2018, the end of the Iranian calendar year. That did not come to pass and may have been related to ongoing issues with the Simorgh design. Iran has successfully launched domestically produced satellites in the past, but using the smaller Safir space launch vehicle.

Whatever the exact state of the Simorgh program and Iran’s space program as a whole are, the official admission that the latest launch failed is notable for a country that routinely exaggerates its technical achievements. Iranian authorities did not publicly announce the failure of the 2017 launch themselves, though it was widely reported in the international press.

Open discussion of space launch activities could be a sign of the Iranian government’s growing confidence in its space capabilities, despite the failures. Historically, it is hardly uncommon for national space programs to suffer major setbacks. Any failure still provides useful information for future developments, too.

The public announcement of the space launch plans and the outcome of the launch also point to a desire to legitimize the program in the face of criticism from many of Iran’s chief international opponents, including the United States and Israel. The U.S. government, in particular, had lambasted the Iranian government about its launch plans and warned them not to go through with it at all.

“The United States will not stand by and watch the Iranian regime’s destructive policies place international stability and security at risk,” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement on Jan. 3, 2019. “We advise the regime to reconsider these provocative launches and cease all activities related to ballistic missiles in order to avoid deeper economic and diplomatic isolation.”

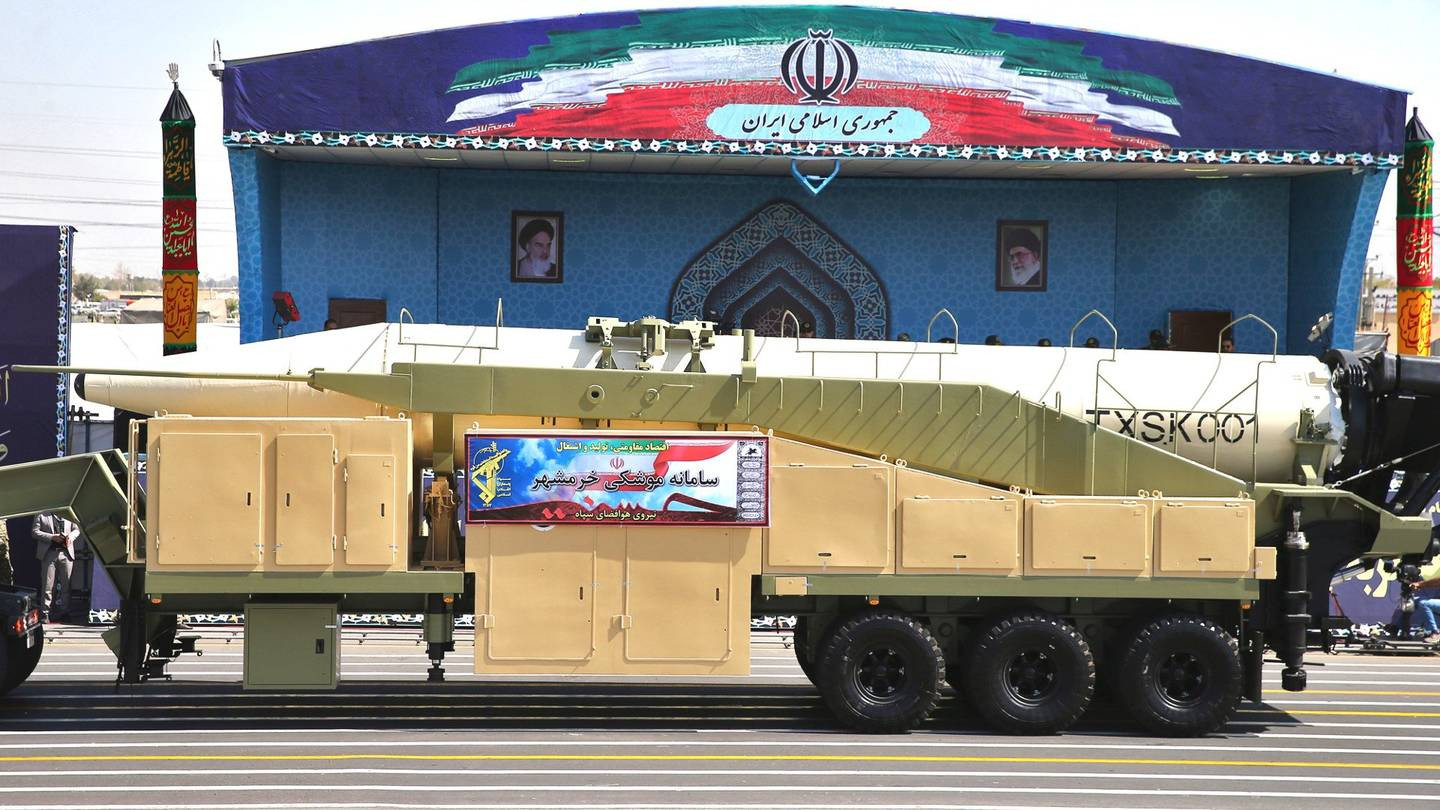

The crux of the U.S. government’s argument is that launch vehicles, such as Simorgh, are analogous to long-range ballistic missiles and that the Iranian space program is simply a cover for their development. In turn, these space launches are then in violation of various U.N. Security Council Resolutions that demand Iran cease development of ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons.

Other American allies, particularly Israel, share this opinion. The United Kingdom, France, and Germany, all condemned the 2017 launch, but have not been as vocal about this latest Simorgh flight.

The United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany, along with China and Russia, had been parties to the controversial deal over Iran’s nuclear program, officially known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which they all signed in 2015. President Donald Trump pulled out of that arrangement in May 2018.

Not surprisingly, Iran rejected Pompeo’s warning and the country does not believe that either its space program or its ballistic missile developments violate any U.N. Security Council Resolutions, which specifically talk about work on systems that could potentially carry nuclear weapons. The Iranian government says that since it is not actively working on nuclear weapons, none of its missiles can be understood to be potentially nuclear capable.

Information the Israeli government recently obtained on Iran’s nuclear program has offered greater detail about activities prior to 2003, but has offered no evidence that Iran has had an active program working to build an actual nuclear weapon since then. However, the country did continue enriching uranium, ostensibly for civilian purposes, afterward, which Iran scaled back after agreeing to the JCPOA. Iranian officials have threatened to resume enriching uranium to higher levels of purity, which could point to a rebooted weapons program, in response to recent American sanctions.

Regardless, the Simorgh launch is likely to further inflame tensions between the United States and Iran, have been steadily growing since the U.S. government left the JCPOA. In November 2018, the Trump Administration reimposed all of the sanctions that it had previously relaxed under the Iran deal.

Since then, the United States has been pressuring its allies and partners to further isolate the regime in Tehran, which continues to support terrorists and militants around the world and commit human rights abuses at home, among other things. The results have been decidedly mixed and the remaining parties to the JCPOA have been working to try and keep that deal alive despite opposition from the U.S. government.

In addition, countering Iranian influence steadily became a core part of the U.S. military’s mission in Syria and has been at the center of America’s continued support for the controversial Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. On the Iranian side, in 2018, officials in Tehran made numerous threats to close off the strategic Strait of Hormuz leading into the Persian Gulf and enabled Yemen’s Houthi rebels to launch attacks on commercial shipping and warships in the Mandeb Strait separating the Red Sea from the Gulf of Aden.

More seriously, a recent report from the Wall Street Journal also said that the White House had asked the Pentagon to provide options for a military response following rocket and mortar attacks on the U.S. consulted in the Iraqi city of Basra and the American Embassy in the capital Baghdad during widespread protests in September 2018. After those incidents, the United States temporarily relocated diplomatic staff elsewhere. Secretary of State Pompeo publicly blamed Iranian-backed militias and Iran’s Quds Force for the attacks.

It remains unclear how directly Iran might have been involved. The Quds Force, part of the powerful quasi-military Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), is responsible for training and advising militant groups overseas and publicly supported the development of Shia militias in Iraq, ostensibly to fight ISIS terrorists. It has also been active in Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere in the region, notably supporting groups fighting Israel.

In addition, beyond Pompeo’s remarks, National Security Advisor John Bolton has also long been an advocate for taking military action against Iran to curtail any potential nuclear capabilities. There is a growing concern that the hawkish stance of the Trump Administration is increasing the likelihood that Iranian provocations might lead to an actual skirmish of some kind.

“As we have been warning for some time, Iran’s missile testing and missile proliferation is growing,” Pompeo wrote in another statement condemning an actual Iranian ballistic missile test on Dec. 1, 2018. “We are accumulating risk of escalation in the region if we fail to restore deterrence. We condemn these activities, and call upon Iran to cease immediately all activities related to ballistic missiles designed to be capable of delivering nuclear weapons.”

On top of this, the future of the Syria mission is now in question after President Trump announced plans to withdraw all American forces from that country in December 2018. He then upset members of the present coalition government in Iraq by not meeting with the country’s Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi during a surprise visit to the country later that month. Abdul-Mahdi’s political bloc has sought to improve the country’s relationship with Iran and some members of parliament are now calling for a complete pullout of U.S. forces from the country. These developments could further contribute to the United States seeking new ways to challenge Iran’s position in the region and Iranian responses in kind.

“It is important to know also that we will not ease our campaign to stop Iran’s malevolent influence and actions against this region and the world,” Pompeo said during a speech in Cairo on Jan. 11, 2019, which came at the start of a regional tour to visit America’s Middle East allies. “The nations of the Middle East will never enjoy security, achieve economic stability, or advance the dreams of their people if Iran’s revolutionary regime persists on its current course.”

So far, the U.S. government does not appear to have issued a direct response to the latest space launch. How the United States and Iran choose to respond, or not, especially given the failure of the satellite to reach orbit, could further escalate tensions and increase the potential for actual alterations between the two countries, or their proxies.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com