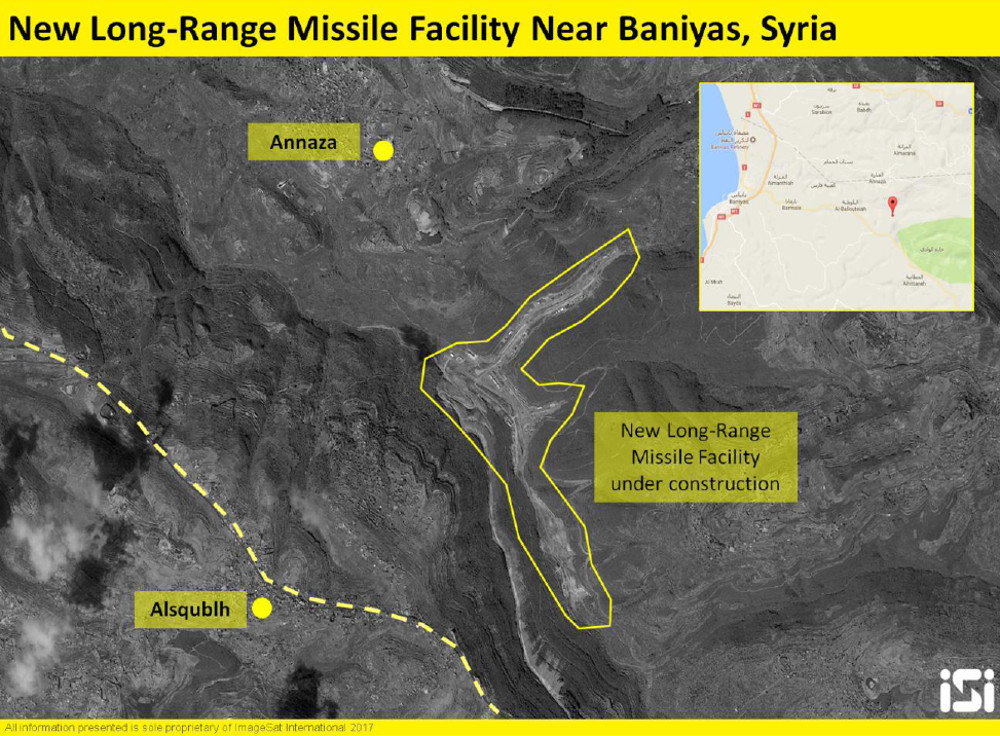

Satellite imagery appears to confirm earlier reports that Syria is building a new ballistic missile production complex near the city of Baniyas. Various features at the site suggest that the Syrian regime of Bashar Al Assad is actively working with the Iranian government on its construction and that it may be part of a larger regional effort by Iran to bolster its allies’ capacities, especially against Israel.

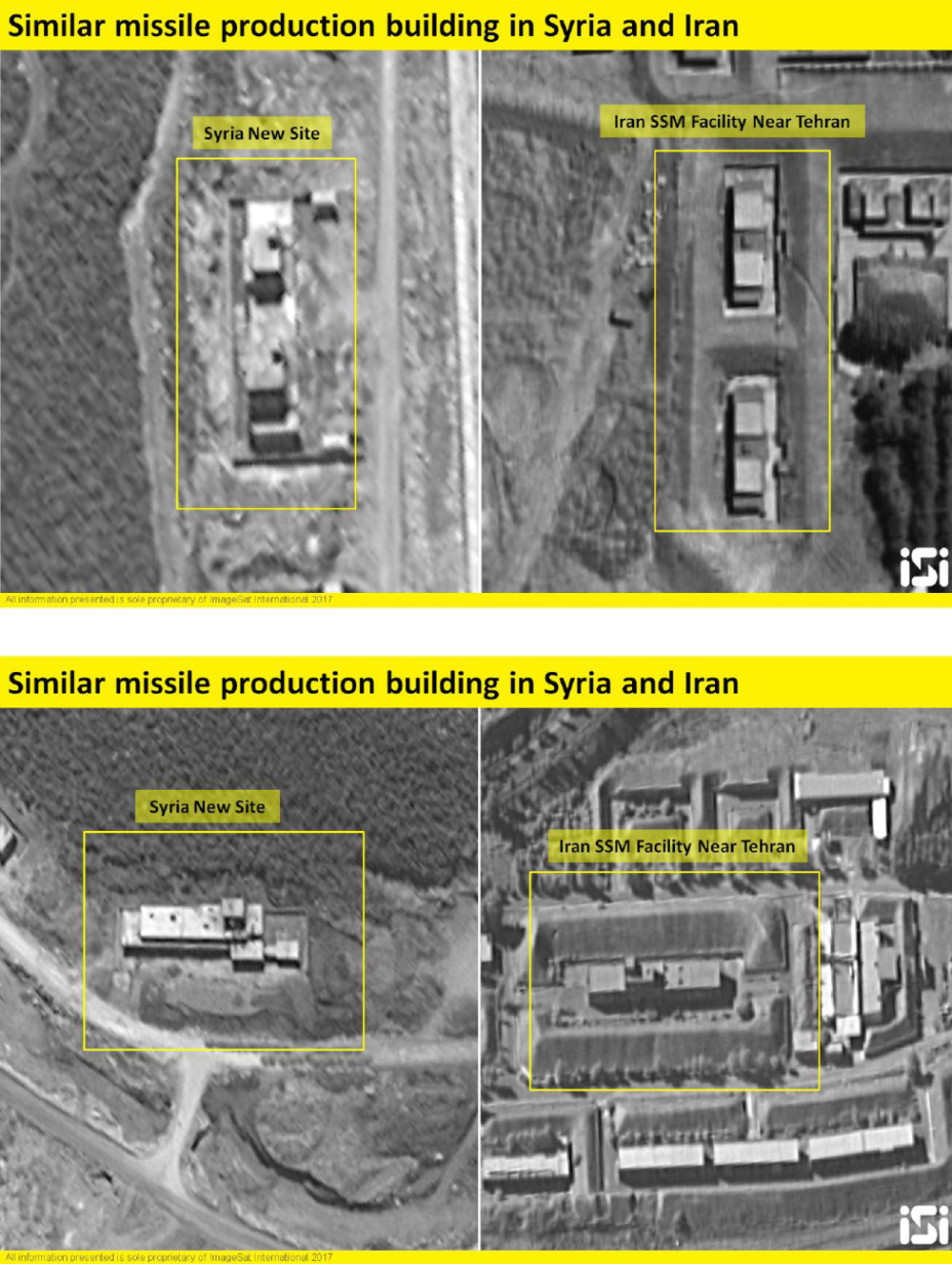

Earlier in August 2017, ImageSat International (iSi), a private satellite imagery and geospatial intelligence firm, published the images, taken with its EROS-B satellite, of the area in western Syria, along with its own analysis. Based on the imagery alone, the company’s analysts concluded that the buildings were very similar to structures seen in Iran that are associated with the production of short range ballistic missiles, but that the exact extent of Iranian involvement as unclear. Work on at least one portion of the facility seemed to be still ongoing, as well.

“According to ISI’s intelligence team, the site still under construction includes one entrance that leads to the road to the site,” the firm noted in its report. “The site includes administration area, production area and storage area. The site also has an area that is apparently dedicated to the production of ammunition.”

ISI did not identify the exact location of the comparative sites in Iran, but other analysis shows that they are buildings at the Iranian military’s secretive Parchin complex situated nearly 20 miles southeast of the country’s capital Tehran. The particular portions of the facility that are similar to those in Syria are reportedly associated with the production of solid fuel Scud, Fateh 110, and Zelzal short-range ballistic missiles.

The earthen berms around many of the buildings were perhaps the most significant comparative features. This type of physical protection is commonly associated with factories making ammunition, solid fuel rocket motors, and similar items and is designed to spare nearby structures from damage in the event of an accident.

The first report of the existence of this new complex came from a website, zamanalwsl.net, which is associated with the Syrian opposition groups, on June 28, 2017. The activists said that their sources had informed them that Assad himself had visited the missile factories earlier in the month under the cover of visiting the families of supporters in the area.

“The sources mailed us aerial photographs of the area which show the facility, consisting of several buildings, and noted that it is under the direct supervision of the Iranians,” the writers on zamanalwsl.net explained, according to a translation by the Middle East Media Research Institute. “It is a facility for developing and manufacturing long-range missiles, and the sources assess that it will be officially opened at the end of this year. According to them, during his visit to the facility Assad held an extensive meeting with several ‘Iranian and Syrian experts,’ lasting about two hours.”

In June 2017, MEMRI said it was unable independently verify any of the claims. Though the imagery now shows that the site near Baniyas is almost certainly a missile factory, it less clear as to the exact reason why Syria opted to construct the facility there or do so now, and the exact nature of any cooperation with Iran.

There are, however, a number of logical explanations, most of which are not mutually exclusive. The most obvious is that the Syrians may simply not have the existing production capacity to keep their arsenal of short range ballistic missiles steady as they may have used as much as 90 percent of their original stockpile by 2015.

In their initial report, zamanalwsl.net said its sources had also informed them that the construction was part of a larger plan on the part of the Assad regime to consolidate arms production, especially with regards to advanced weapons and weapons of mass destruction, in areas with predominantly Alawite Shia Muslim populations that are solidly loyal to the Assad regime.

This makes good sense. Though Assad continues to boast successes against rebels and terrorist groups, including the recent victory over opposition forces in Aleppo, and continues to enjoy the support and relative safety provided by the Russian military, his regime remains in a tenuous position.

On top of that, as the civil conflict has dragged on and become increasingly brutal, Israel has launched an increasing number of air strikes in Syria. These are primarily aimed at destroying missiles and other advanced weapons bound for ostensibly pro-regime groups, most notably Hezbollah, which Israeli authorities see as a direct threat to their own security interests.

Baniyas is effectively half way between Tartus, where Russian forces maintain a strategic port facility, and Latakia, home of Hmeimim Air Base and the bulk of Russia’s contingent in the country, including S-300 and S-400 long-range surface-to-air missiles and Pantsir-S1 short-to-medium range air defense systems. By building the missile production complex there, it is well protected from both insurgents and preemptive strikes.

For Iran, a cooperative missile factory in Syria could help it skirt the scrutiny of the international community and sanctions on its advanced weapons programs. Iranian officials have long been under pressure to allow arms inspectors into Parchin to look for evidence of banned nuclear weapons work. The government in Tehran has resisted this, insisting that the site is related only to conventional military efforts and is therefore not covered by agreements, such as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly known as the Iran Deal.

“If you look … at past Iranian behavior, what you’ve seen is there have been covert actions at military sites, at universities, things like that,” U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley told Reuters in an interview published on Aug. 22, 2017. “There were already issues in those locations, so are they [the International Atomic Energy Agency] including that in what they look at to make sure that those issues no longer remain?”

Iran might not just have to worry about inspectors prying into restricted military sites, either. In October 2014, there was a massive explosion at Parchin, which many believed was the result of sabotage by Israeli or American intelligence services. A similar “accident” at another facility had killed 17 people, including Iranian General Hassan Tehrani Moghaddam, a top official in charge of ballistic missile developments, in 2011.

Dispersing missile production, and possibly other advanced weapons development work, outside of Iran could help both conceal and protect it from unwanted attention. Experts believe that Syria has hosted similar sites in the past, as well as, such as a nuclear facility possibly linked to North Korea that Israel destroyed in an air strike in 2007.

For both the Syria, cooperation with Iran on ballistic missiles could lead to advancements in its own arsenals with relatively little investment necessary. This would help explain growing evidence of similar sites in Hezbollah-controlled territory in Lebanon, as well.

It is possible the facilities in Syria and Lebanon could eventually move beyond producing just short-range designs in the future, too. This in turn could improve the Assad regime and Hezbollah’s deterrent capabilities against Israel. Localized missile production would be a boon for Hezbollah in particular, which presently has to rely on covert shipments from Iran and Syria, which as we already noted, are often intercepted by the Israelis.

In March 2017, Assad threatened Israel with a flurry of Scud missiles if it didn’t stop attacking targets within Syrian territory, but didn’t follow through. In June 2017, Iran did launch a number of Zulfiqar missiles, a version of the Fateh 110, which the factories in Syria could reasonably produce, ostensibly against ISIS terrorists. However, as The War Zone explained at the time, it seemed likely that this was more an opportunity for Iran to show off the capabilities of these missiles.

For its part, the Israeli military is continuing to develop its own David’s Sling and Arrow ballistic missile systems against exactly these sorts of potential threats. Whether these systems could protect against a large barrage of even short-range missiles coming from Iran, Syria, and Lebanon altogether is another matter.

“We are fully aware” of the missile factories, Israel’s hawkish Defense Minister Avidgor Liberman said at a briefing in Tel Aviv in July 2017. “We know what needs to be done… We won’t ignore the establishment of Iranian weapons factories in Lebanon.”

So, it remains to be seen whether Israel will ultimately feel it can tolerate these new missile factories supplying its enemies with new and possibly increasingly capable weapons.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com