You see all types of crazy looking structures on and around military bases when perusing satellite imagery. But once in a while you find something that is just too bizarre to move on from without an explanation. Looking more like the evil lair of a comic book pharaoh brought back to life than something you would find on an ex-missile test range, the strange installation seen in the banner image above is a burial tomb, but of a different kind.

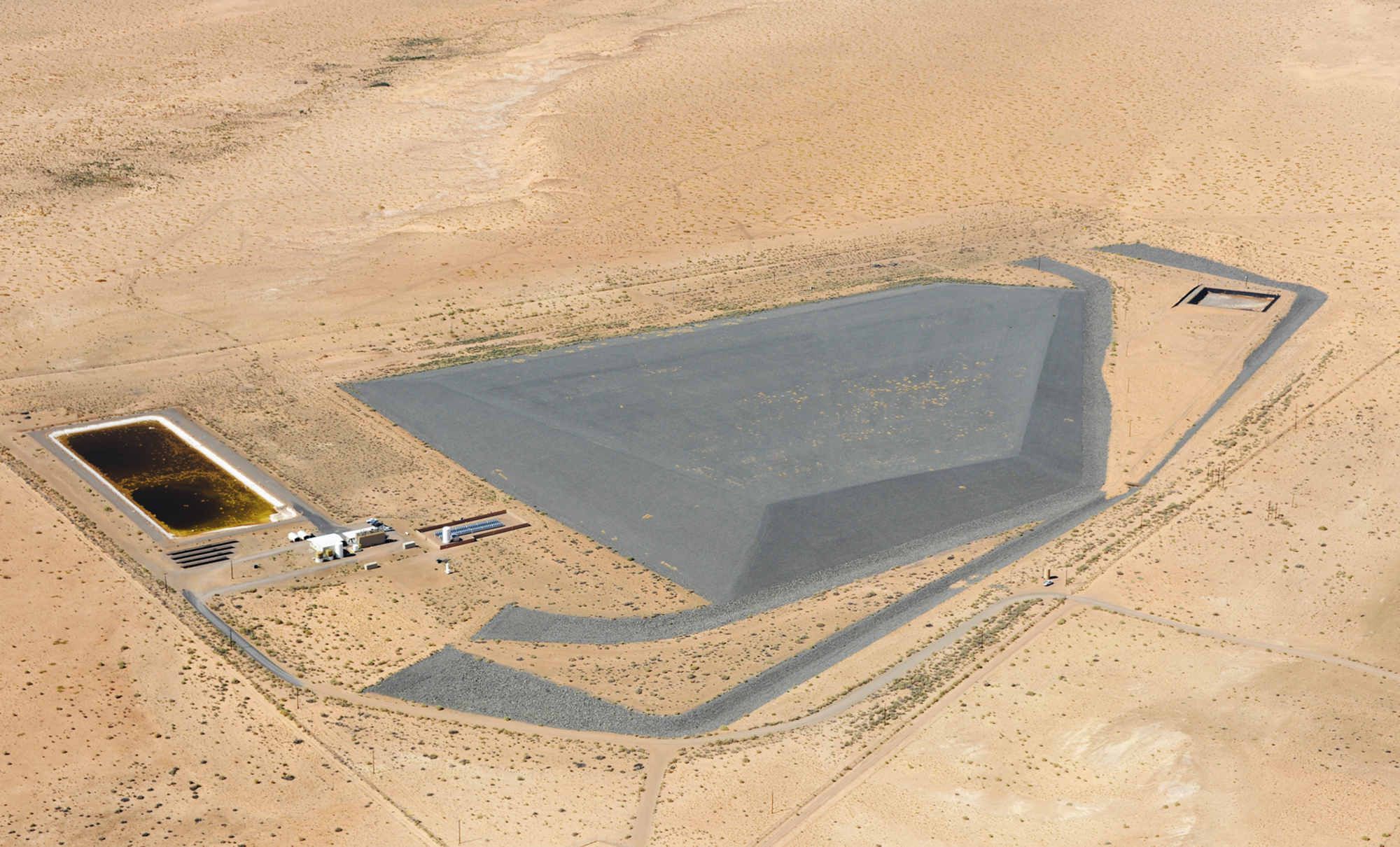

The peculiar site is situated on the western edge of the long defunct Green River Launch Complex in Utah and measures 530 feet by 450 feet—the Luxor Hotel is 600 feet by 600 feet for comparison—and covers five an d half acres. But the thing is that this imposing fixture isn’t even a structure—it’s a pile. What you are seeing in the image above is a giant, contoured mound of radioactive waste.

Originally a mill on the site was operated by Union Carbide from 1957 to 1961—at the height of the atomic age. During just three years of operation as a uranium upgrading facility it produced 183,000 tons of ore and generated an estimated 114,000 cubic yards of radioactive tailings, a predominantly sandy material, that covered about 9 acres to an average depth of 7 feet.

The mill remained for decades after its closure before the State of Utah took over the site in 1988. The DOE then stepped in to manage the disposable of the toxic tailings on the site in 1989. The mound also contains radioactive waste from 17 other sites from the region as well. Dubbed the Green River Uranium Disposal Cell, it is ringed by chain link fencing with signs everywhere warning of the toxic danger of its contents.

Geologicnow.com, an absolutely fascinating site, has an awesome little article about what exactly this thing is, and apparently it has plenty of radioactive cousins splattered around the U.S. that were also born out of the Cold War:

Though the underground nuclear catacombs for America’s spent nuclear fuel are yet to be created, radioactive tombs of America’s various nuclear programs already exist today, with more to come. Most are repositories for the remains of uranium mills, processing facilities, weapons plants, and contaminated tailings, bulldozed into engineered isolation mounds designed to limit contact with their surroundings for hundreds of years. There are dozens of these mounds, across the country from Pennsylvania to Arizona, built mostly by the Department of Energy, and maintained by their Legacy Management office.

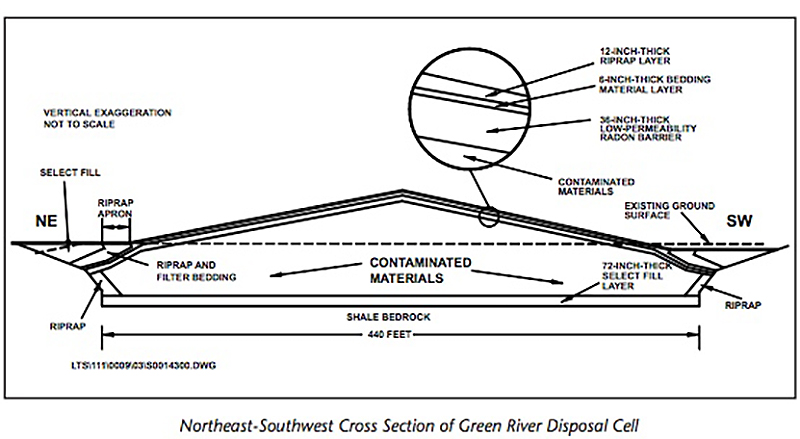

These disposal mounds are generally low, rectilinear piles with flat, sloping tops – terrestrial umbrellas, keeping moisture out of the pile as much as possible. In arid environments, the outer layer is a coating of coarse riprap rock, a dead space where nothing grows, where no soil forms, and no roots take hold that could pierce the radioactive core. This tough skin allows occasional rains to pass through it to the next layer, a low-permeability clayey mixture a few feet thick. Water drains off to the side of the pile through channels at the base held in place with more layers of crushed stone.

These disposal cells are located primarily in the Southwest, where natural uranium deposits were found and exploited. Some of these former uranium mills were set up secretly for the Manhattan Project. Most started in the 1950s, and many operated until the 1990s. Presently, only one conventional uranium mill is operating in the USA, the White Mesa Mill in Blanding, Utah, in the heart of the uranium district and Indian country. However, that may change as the nation shifts towards more self-reliant energy sources.

Each disposal cell covers many acres and as much as half a square mile. They resemble ancient pyramids or relics from a geometrical mound-building culture, like archeological forms made for the future. They represent the legacy of the most advanced technology of a global culture: the creation of the atomic bomb, the ability to destroy the world at the push of a button. They are part of the nationwide network of industrial sites created to extract, process, manufacture, and engineer nuclear fuel for reactors and weapons–a continent-wide landscape machine to concentrate a naturally occurring trace material into such compressed atomic density that it explodes with galactic energy.

These mound sites, byproducts of this effort, are the end of the line, meant to be unconnected to the rest of the world, like deadly anachronistic time capsules. These are the most negative of spaces, nonplaces, meant to stay inert and isolated for as much of forever as possible, kept from the present, but destined for the future.

A fact sheet that is publicly available online about the site includes details about its particular construction:

The cell was excavated to bedrock and was lined with 6 feet of low-permeability soil. Most of the contaminated materials are below grade. A clay-rich soil layer placed over the contaminated materials extends to the edge of the cell below grade and serves as a lowpermeability radon barrier. Above grade, the radon barrier is covered by a layer of rock (riprap) placed on granular bedding material. The cell design promotes rapid runoff of precipitation to minimize leachate. The walls around the edge of the disposal cell are lined with riprap and bedding material. A large riprap apron extends outward from the edge of the disposal cell for about 20 feet. Precipitation flows down the 20-percent side slopes into the surrounding rock apron. The disposal cell was located and designed to prevent or minimize erosion from storm water. The cell is located 75 feet above the Brown’s Wash floodplain. Existing gullies were filled and regraded during cell construction, and all disturbed grass surrounding the disposal cell were reseeded with native vegetation.

The document continues, stating:

The disposal cell at Green River is designed and constructed to last for 200 to 1,000 years. However, the general license has no expiration date, and DOE understands that its responsibility for the safety and integrity of the Green River site will last indefinitely.

So like the pyramids of Egypt, these are also eternal resting places with the contents within not ever intended to be moved or molested. An indestructible reminder of a very dark time in mankind’s past. One also has to wonder what toxic impact this waste had on its surrounds before it was organized into a neat and isolated, albeit huge pile?

As for the Green River Launch Complex, the largely abandoned site may ring a bell as it was ridiculously claimed by Popular Mechanics in 1997 that operations at Area 51 had packed up and moved there, as well as to Dugway Proving ground that lies about 200 miles to the Northwest. This was totally unsubstantiated and incorrect, but the myth propagated for years and drew attention to the crumbling base.

Now, even as the base’s once important Cold War infrastructure continues to be demolished or just disintegrate with the passage of time, that huge charcoal colored pile of atomic waste will sit begrudgingly for ages.

Some things mankind simply can’t reverse and the Green River Uranium Disposal Cell is a stark and ominous reminder of that.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com