President Donald Trump is still adamant about the need to move forward with his signature plans to build a new wall all along the U.S. border with Mexico. Critics have called into question how effective this obstacle will be, as well as its potentially exorbitant costs, while supporters say it absolutely necessary and that it will work, often citing reports that prototypes were able to keep out highly trained U.S. military special operators during testing. Thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, The War Zone has now obtained a highly redacted copy of the official report on those experiments, which, unsurprisingly, paints a more complicated and nuanced picture of the barriers’ possible capabilities.

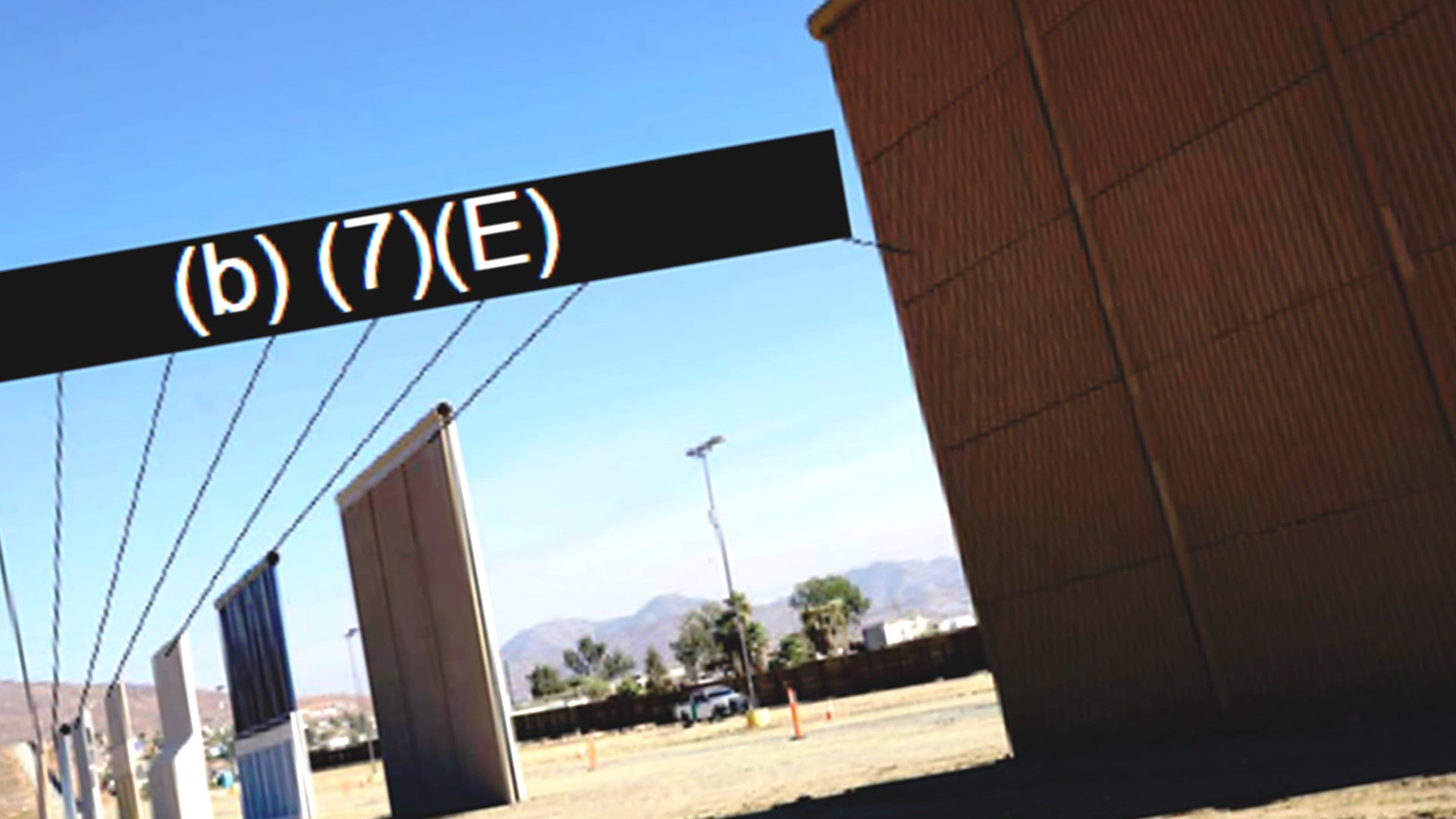

Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) led the “Border Wall Mockup and Prototype Test,” which ran from Oct. 24 through Dec. 15, 2017. The testing regime included attempts to breach and scale the eight prototype walls, or representative sections thereof, as well as evaluations of how easy eight different prototype wall sections were to construct, assessments of their overall design, and surveys about how pleasing to the eye and how intimidating they looked. Earlier 2017, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had handed out contracts, ranging in value between $300,000 and $500,000, for the prototypes, which are between 18 and 30 feet high and made from various materials, including concrete and metal.

“The Mock-up and Prototype Test is part of a larger concept development phase to determine which design attributes most effectively and efficiently meet CBP’s operational requirements for the Border Wall Program as part of an overall Impedance and Denial (I&D) capability,” the report, which is dated Feb. 23, 2018, explains in its executive summary. “The results of the test were not intended to provide direct conclusions or pass/fail scoring.”

The Associated Press was first to report on the tests in January 2018, citing information from what was likely a draft version of the report we have obtained that an unnamed source relayed to them. Versions of that story still carry headlines such as “Trump’s border wall prototypes pass tests by military special forces” and “Border Wall Models Thwart US Commandos In Tests.”

For the breaching tests, which occurred between Nov. 28 and Dec. 16, 2017, CBP split personnel into four teams, each of which was responsible for trying to get through with two different breaching techniques. We don’t know the exact breakdown of the teams, but they included 10 individuals from CBP’s specialized Border Patrol Tactical Unit (BORTAC), 10 personnel from the U.S. Army’s 7th Special Forces Group, and two members of the Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC).

CBP did not turn these teams loose on the eight actual border wall prototypes, which remain standing at a site outside San Diego. Instead, the law enforcement and military personnel tried to break through representative mock-ups at a separate, unspecified location.

Not unreasonably, censors redacted all information on the methods themselves, citing an exemption for law enforcement-related information. We do know that the testers were able to employ nearly 60 different tools and other pieces of equipment across the eight breaching experiments, but it’s not clear if they tried every tactic against all eight mock-ups. We also know that the first breaching technique, or BT-1, proved to be so ineffective that CBP removed it from the test points entirely.

In each case, the breachers had to try to make hole in the wall within a set amount of time. A “breach” occurred when that gap reached a certain diameter, which is redacted in the report. We do know that each team had a measuring disc to determine whether or not they had made sufficient progress. Evaluators were on scene to collect additional information, such as how physically exhausting the task was for the individuals involved and whether that might be a deterrent.

There is no indication that any of the teams were able to breach any of the eight wall types using any single one of the eight methods available to them. At the same time, the report suggests that the teams only attempted to use each breaching method on a portion of the mock-ups that was as free of damage as possible and that a combination of techniques applied to the same area may have been enough to break through one or more the wall types.

One test led a mock-up to suffer “compromised structural integrity” ahead of a subsequent experiment, according to CBP’s report. This, in turn, led to “unsafe conditions” and the cancellation of a portion of the testing program for that mock-up.

We also don’t know what the determining factors were in deciding how large the hole in the wall would have to be for CBP to consider it a breach. As we at The War Zone have noted before, the space necessary for a person to fit through is much different from that required for smugglers to simply pass packets of drugs or other contraband to individuals on the other side.

In addition, the report confirms that the test personnel did not have access to explosives, vehicles, or other breaching methods. Breaching also only involved attempting to pierce through the wall directly, not tunnel under it.

The scaling tests occurred almost concurrently, running from Nov. 28 to Dec. 16, 2017. In this instance, six BORTAC members and a lone individual from the 7th Special Forces Group tried to get over the eight prototype wall sections. Just over 20 pieces of equipment were available to these personnel for the tests. Again, citing security concerns, CBP redacted the specifics of each scaling method.

However, “each prototype was attempted to be scaled with techniques appropriate for each design, as determined by the scaling experts,” according to the report. “Scaling techniques were developed prior to the test, and after the scaling experts were able to practice on the prototypes, the scaling techniques were modified as appropriate and additional techniques were developed.”

As was the case with the breaching tests, the scaling experiments were all timed scenarios giving individuals a limited amount of time to get to the top. It is unclear whether or not each scaling technique involved a single person or a team, though the Associated Press’ report in January 2018 said no single individual was able to climb higher than 20 feet without assistance.

As such, it remains very possible that a determined team could ascend and descend, though it could take them a significant amount of time and could potentially make them vulnerable to patrolling law enforcement personnel. At the same time, as we have noted in the past, human traffickers especially might not be concerned about the safety of getting up and down from the wall, leaving individuals or small groups to weigh the risks of personal injury or being stranded in an inhospitable area along the border.

In addition, neither the breaching nor the scaling tests took into account any other means of mitigating the barrier, such as attempting to smuggle people or contraband through established border checkpoints or via air or sea routes. Drug smugglers, in particular, have been experimenting with using a variety of methods to simply toss their goods over existing walls, too. CBP’s tests did not give BORTAC and U.S. military special operators a chance to try to build oversized air cannons and attempt to simply launch objects over the prototype barriers.

Of course, a wall made up of one or more of the different prototype construction methods is very likely to serve as a deterrent to those individuals who are simply seeking to cross the border and may fulfill that purpose just by presenting a particularly visually imposing barrier. CBP evaluators have recommended employing more than one particular type in order to have obstacles that are best matched to the particular terrain features in a given area.

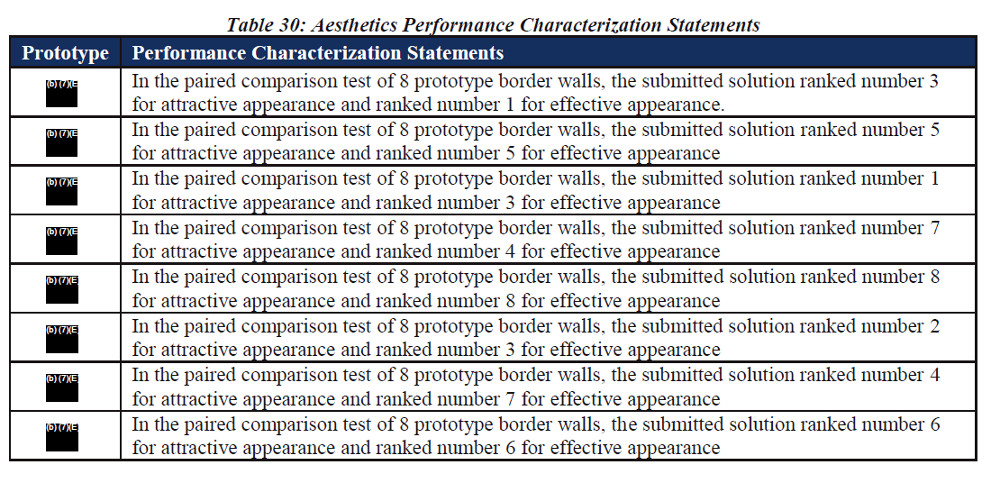

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about the specific construction and design benefits of the different wall designs, since CBP redacted the bulk of that information, include essentially of the basic requirements they had laid out. Their censors even removed most of the data on how 76 individuals, including 34 average residents of the greater the San Diego area, had rated how pleasing and threatening each of the eight prototype walls looked.

These individuals were asked to rate factors the wall’s color hue, how smooth or rough its texture appeared, whether they liked any patterns in the design, and how the top of the wall prototype looked compared to the rest of it. They were then asked to provide similar rankings for whether the texture and the top design looked “appropriate” for an ominous barrier, how impenetrable it looked to the naked eye, and how well it provided general situational awareness.

The last category has been important for the border patrol from an operational perspective. At least one of the prototypes includes a slatted bottom section that would allow law enforcement personnel to see through it and better spot individuals attempting to get through.

But we have little idea how the people CBP surveyed responded. Censors redacted their final rankings of how appealing and intimidating they found the eight different structures, citing the FOIA’s (b)(7)(E) exemption. This allows the U.S. government to withhold information that “would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions or would disclose guidelines for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions if such disclosure could reasonably be expected to risk circumvention of the law.”

All this being said, whether or not the Trump Administration’s border wall project will even proceed remains to be seen. Members of Congress are still locked in a battle over funding for the project. President Trump has suggested he could seek to use U.S. military funding for the barrier, but there just isn’t enough money in the readily available portions of the Defense Department’s budget to pay for the construction, which could cost tens of billions of dollars in total, according to some estimates.

What we can glean from the test report continues to raise additional questions about how effective any final wall might be in under various circumstances. But it also indicates that CBP would very likely conduct more rigorous and quantifiable testing to determine which designs might pass or fail various requirements if the project were to go ahead.

CBP itself says that you shouldn’t draw any direct conclusions from these experiments, though, not even about whether the prototypes looked pretty, pretty scary, or both.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com