Insurgents are using small unmanned aircraft to regularly monitor activity at a major American base in Afghanistan. This is yet another example of how the Taliban and other militant groups in the country are expanding their capabilities and further highlights the increasingly common threat of readily available commercial drones to nation-state security forces both on and off the battlefield.

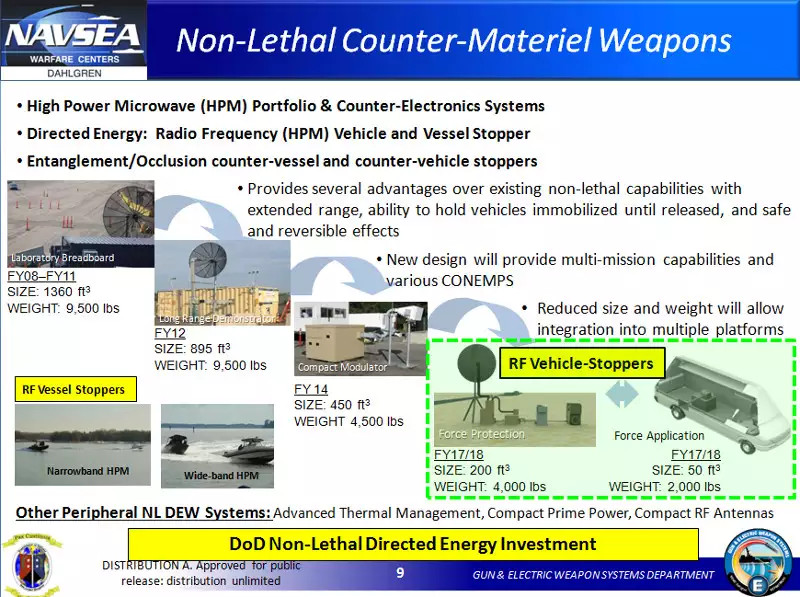

Tom Lockhart, the Director of the Strategic Development Planning and Experimentation Office (SDPE) at the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), disclosed this detail during a test of various counter-drone technologies at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico in October 2018. At present, SDPE is exploring the viability of solid-state lasers and high-power microwave directed energy weapons as base defense tools against tiny unmanned aircraft.

“Coming back from Afghanistan last year in October [2017], I was at a base where we had a lot of unmanned systems sitting over and watching everything we do,” Lockhart explained in an interview at White Sands. “For the future, our airmen would like to not be monitored 24/7 and this will push that [the drones] back so they [the militants] don’t have that monitoring capability.”

The SDPE director did not say what base he had visited in Afghanistan. The U.S. military has personnel at various locations across the country, but the Air Force’s two biggest operating locations at Bagram Airfield, situated north of the capital Kabul, and Kandahar Airfield in the southern province of the same name. Another AFRL researcher was assigned to Bagram in July 2017, supporting a field test of unspecified counter-drone systems.

“Air Force has three major areas [of directed energy research and development], air base defense, precision engagement, and aircraft self-protect,” Dr. Michael Jirjis, Chief for Directed Energy Experimentation at AFRL, added in his own interview at White Sands. Base defense “is the first, probably near-term low-hanging fruit that we can actually get after as we start opening up the bottleneck for directed energy, transitioning it … to operationalizing it.”

Video of the testing at White Sands, seen above, shows at least three different systems at work. Two of these were solid-state lasers, while the last one was a high-power microwave. All three have various sensors, including electro-optical and infrared cameras, to spot and track their targets.

Lasers physically destroy their targets, burning holes in them, while high-power microwaves might simply disrupt the drone’s ability to communicate with its operator. A burst of high-power microwave energy would also be enough to fry the electronics inside the unmanned aircraft, depending on how powerful the directed energy beam is and how far away the target is from the weapon.

The first of the laser-based counter-drone systems was a trailer-mounted arrangement from defense contractor L3, which appeared visually similar, if smaller, to the proven AN/SEQ-3 Laser Weapon System (LaWS) that the company developed for the U.S. Navy. Developing a static, land-based version would be a relatively low-cost and low-effort way of producing at least an interim laser base defense system with a known capability to destroy small drones.

The other laser system was from Raytheon. The Massachusetts-headquartered company debuted the turreted weapon system, which uses many components from its Multi-Spectral Targeting System (MTS) sensor turret, in 2017.

Raytheon has been demonstrating this directed energy weapon using the popular Polaris MRZR all-terrain vehicle as the platform, highlighting its compact design and rapid deployability. For Air Force base defense purposes, where drones might only appear briefly at extreme edges of critical infrastructure on the base before retreating to safety, having a mobile system would be especially valuable.

On top of that, directed energy weapons are notoriously sensitive to environmental conditions, with the beams often becoming more diffuse at extended ranges. A mobile platform could help mitigate these issues, since the operators would have more flexibility to simply close the distance to the target.

The high-power microwave, another Raytheon product, was another trailer-mounted system, but was significantly larger than L3’s laser weapon. The design is reminiscent of microwave directed energy weapons the U.S. military has been developing to disable vehicles on the ground, such as car bombs that might be speeding toward a base’s main gate. It is possible that either laser or microwave-based systems could have secondary roles engaging targets on the ground, as well.

As SDPE’s Director Lockhart noted, these systems have given even small, non-state groups a cheap and readily available tool to monitor their opponents as never before. For the Taliban, or other insurgent groups in Afghanistan, having that capability would help them track force movements within the base to help plan or execute attacks. The could also observe forces arriving or departing the base, which could signal an impending offensive or a shift in attention to another region.

Videos that these small drones might capture have a propaganda value as well, especially if taken during an actual attack. The Taliban, among other insurgent groups around the world, are well aware of how useful this footage is for recruitment efforts and for sapping the morale of their opponents.

Militants have shown that these small drones can be weaponized, too, which makes them even more dangerous. ISIS, in Iraq and Syria, helped shove the image of a modified quad- and hex-copters dropping small grenade-like munitions into the modern military consciousness. In January 2018, Syrian rebels conducted a relatively long-range mass drone attack on Russian bases in that country, helping to further highlight the evolving scope of the threat.

In August 2018, Venezuela’s dictatorial President Nicolas Maduro survived an assassination attempt by hex-copters loaded with explosives, making it clearer than ever that concerns about these systems are hardly limited to traditional conflicts. Even if the small bomblets that these drones are capable of carrying do not do significant damage to their targets, their ability to strike at opponents, often with little warning, in areas that nation-state security forces often view as safe, can only have a demoralizing effect.

So, it’s not surprising that the Taliban may be making even greater use of small drones than in the past. The group has already been working to expand their technological capabilities to enable steadily bolder attacks on Afghan security forces and the U.S.-backed coalition when they least expect it. Night vision, especially, has given the insurgents a means of challenging America’s long-held advantages during engagements after dark. It has provided the militants with a decided edge over more poorly equipped Afghan troops and police, too.

Of course, this threat is hardly new, but the United States is still playing catch-up after decades of almost completely ignoring potential aerial threats, manned or otherwise, entirely. The directed energy weapons the Air Force was testing out at White Sands are just some of a wide array of man-portable, mobile, and static defense systems that the U.S. military as a whole is testing now as it rushes to fill these obvious capability gaps.

These include everything from shotguns firing small nets to automatic cannons, hit-to-kill interceptors, and missiles. There are individual jammers that can block the signal to the drone from the operator and even other drones to intercept and destroy incoming threats.

Various companies are developing new and improved supporting sensors, including compact radars, to improve the ability of a complete system to detect and engage small targets. As concerns about hobby drones have grown, an entire industry working on countermeasures has grown with it.

Swarms of drones networked together and operating in concert look to be the next evolution of the threat. This, in turn, is already driving the development of new defenses.

Hopefully, the Air Force will be able to prove that directed energy weapons for base defense are indeed “low-hanging fruit” and field one or more operational systems in the near term. The SDPE’s director can attest himself, the threat of small drones is not only real, but is an issue Amercian personnel are staring down every day in real conflict zones without necessarily having ways to combat them.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com