After the U.S.-led missile strikes on Syrian regime chemical weapons sites, the Russian government responded with a number of vague and unspecified threats, including the suggestion it could reconsider selling S-300 surface-to-air missile systems to Syria’s dictator Bashar Al Assad. Now there is a report that Russia is delivering these and other weapons to Syria’s government, including one saying it is doing so under the cover of an actual physical smoke screen, as well as reinforcing its own air defense posture in the country.

As of April 20, 2018, there were reports that numerous Russian-flagged roll-on-roll-off freighters were docked in the Syrian port city of Tartus, which is also home to a Russian naval base. For years now, there has been a steady parade of these and other types of cargo-carrying ships to Syria, as the Kremlin continues to resupply both its own forces in the country and those of its client Assad. In this case, though, it could indicate a surge in deliveries to restock the regime’s arsenal or expand its capabilities.

“A few years ago at the request of our partners, we decided not to supply S-300s to Syria,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told the BBC in an interview on April 16, 2018. “Now that this outrageous act of aggression was undertaken by the US, France and UK, we might think how to make sure that the Syrian state is protected.”

In the immediate aftermath of the American, British, and French missile strikes on Syria in the early hours of April 14, 2018, Russian Colonel-General Sergei Rudskoy, Chief of the Main Operational Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, also said Russia would reconsider the S-300 deal. On April 19, 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s personal spokesperson Dmitri Peskov declined to confirm or deny this was the case in response to a direct question from state-run media outlet TASS.

“We warned that such actions will not be left without consequences,” Russian Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Antonov had also said in more nebulous remarks on April 14, 2018. “All responsibility for them rests with Washington, London and Paris.”

On April 20, 2017, Zvezda, the Russian Ministry of Defense’s official television channel, posted a video online that hyped the capabilities of the modernized S-300PMU-2 “Favorit” variant specifically and again indicated there was a possibility the Kremlin could deliver the weapons to Syrian forces. Russia has already deployed this system with its own contingent in the country, as well.

But rumors are now swirling that S-300s for Assad’s government were among the actual cargo on at least one of the ships in Tartus. A pro-regime source on social media said it was even more likely this was the case since the ships’ crews, or personnel on the docks, had deployed actual smoke screens to shield their activities.

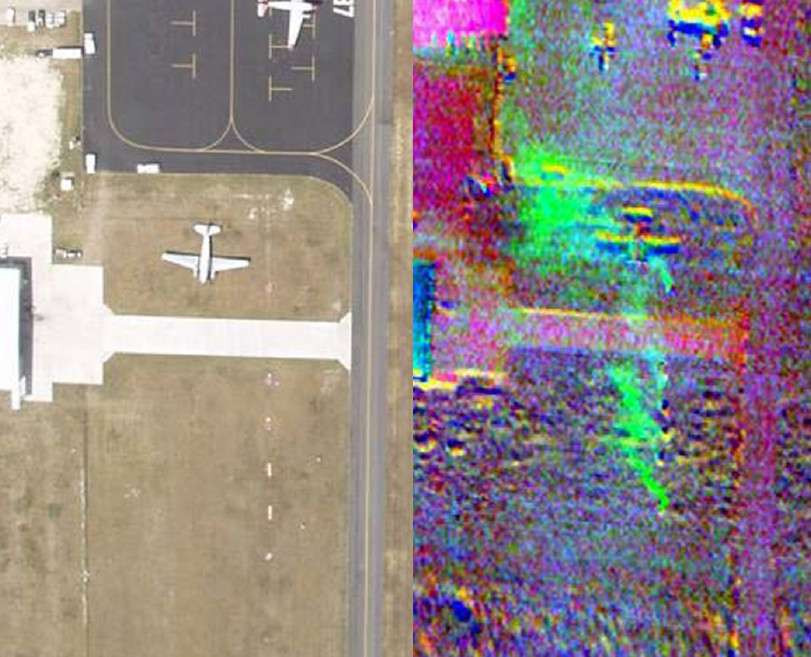

This was reportedly an effort to blind foreign spy planes, drones, or satellites from observing the offloading of sensitive equipment, but it’s unclear how well such countermeasures would necessarily work. American manned and unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft do routinely peer into Syria while flying over international waters in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

The smoke would blind any electro-optical cameras and could defeat some infrared optics depending on the exact chemical and physical composition of the screen. Still, many of these aircraft, such as the RQ-4 Global Hawks that online flight tracking software routinely spots in the area, carry imaging radars and multi-spectral cameras specifically in order to be able to pierce through these types of obscurants.

In an age where so many people have cell phones with cameras in them, the smoke screen could be more about preventing average citizens from grabbing images of advanced military equipment and posting them on social media, as has happened with other major Russian military developments in Syria in the past. However, one would also imagine that if there was a smoke screen, that this would have been intriguing enough to warrant a few pictures itself.

But, as yet, we no additional evidence or independent confirmation to support this claim or indicate that any actual S-300s have arrived in Syria. In addition, the first reports that Russian ships were offloading in Tartus came on April 18, 2018.

The most likely ship in question, the Alexandr Tkachenko, transited the Bosphorus strait, which links the Black Sea to the Mediterranean on April 13, 2018. It therefore almost certainly loaded its cargo in Russia before the American-led missile strikes and the Russian threats to send S-300s to Assad.

That’s not to say that we don’t know if the ships were carrying any military gear, though. Alexandr Tkachenko was very visibly carrying a mix of Project 03160 Raptor inshore or riverine patrol boats, BMK-T bridge erection boats, and various trucks in the open on its top deck as it headed to Syria. Additional vehicles, weapons, or other equipment – which could include the reported S-300s – would have been in the hold. Another piece of military gear was visible on the deck of the Sparta II as it headed toward Tartus on April 19, 2018.

The BMK-Ts are worth highlighting, given that we at The War Zone have previously noted that there are indications that the Syrian government’s river-crossing capabilities are extremely limited. At the same time, pontoon bridge and mobile ferry type systems are essential for Assad’s troops looking to rapidly move back and forth across the Euphrates River into areas under the control of U.S.-backed Kurdish and Arab forces in the continued absence of purpose-built bridges.

It is very likely that such equipment played an important role in getting a battalion-sized force of Assad-aligned militia and Kremlin-linked Russian mercenaries over the Euphrates near the city Deir ez-Zor, where they went on to attack American troops and their partners. Combined with the Raptor boats, this might be a sign that the Syrian regime is looking to step up operations into eastern Syria, or otherwise reinforce its presence along the river, which largely serves as the de facto boundary with American forces.

And whether or not the Russians have been working to expand the Syrian government’s own air defense capabilities, they do appear to be reinforcing their own posture in the wake of the American-orchestrated strikes. Since that operation occurred, a number of additional Pantsir-S1 air defense systems have appeared around Russia’s Tartus naval base, as well as its Khmeimim Air Base further north in Syria’s Latakia governorate.

At Tartus, at least one of these air defense vehicles was situated out on a pier at Tartus, where it would be well positioned to defend against attacks on ships in the harbor. Elsewhere, another one of the other newly apparent Pantsir-S1 positions was guarding a larger S-400 surface-to-air missile system.

The Pantsir-S1, which has both short-range surface-to-air missiles and a pair of 30mm automatic cannons, along with its own onboard fire control radar, is well suited for point defense against aircraft and smaller targets, including drones and cruise missiles. The Russians have long claimed the system, which they have also supplied to Assad’s forces, has developed a particularly stellar record in Syria, including defending against unmanned aircraft and improvised rockets.

Overall, these deployments are not necessarily surprising. Pantsir-S1 is by far the most credible point defense Russian forces in Syria have to defend their critical infrastructure in the country against a cruise missile attack. It also helps explain why they have hurried delivered these same systems to Assad’s forces.

And in 2017, Russia officially linked its air defense assets in Syria with those of Assad’s military. This seemed to be a clear attempt to make the United States and its partners think twice about striking the regime again after an earlier missile strike against Shayrat Air Base.

With that apparently not having deterred the latest American, British, and French strikes, the Kremlin may be trying to once against make the prospect of similar future operations more complicated and risky. They could also see a need to bolster Assad’s own air defense posture in some way, or at least give the appearance of doing so, after the Syrian military’s absolutely humiliating inability to respond to the incoming missile barrage.

The Syrian Ministry of Defense posted the video below online on April 17, 2018. It shows various air defense systems the country has in service, but does not include any evidence of S-300 surface-to-air missile systems.

Despite extremely dubious claims from the Russian ministry of defense, Syria’s air defenders, including those equipped with Pantsir-S1s and other Russian-supplied short-to-medium range air defense systems, do not appear to have shot down any of the incoming missiles, or at least enough of them to keep them from totally obliterating their targets. On top of that, according to one report, they only managed to fire two surface-to-air missiles as the strike was occurring and fired dozens of additional missiles blindly at nothing after the damage was done.

Any new S-300s could also simply go toward expanding the size and overall capabilities Russia’s own air defense posture in the country. If does turn out that there were any of these weapons on the Alexandr Tkachenko, it could indicate the Kremlin was already looking to bolster these defenses in light of very public threats of strikes from President Donald Trump and others leading up to the actual operation on April 14, 2018.

Separately, Iran appears to be, or at least have been, considering a similar response to growing Israeli strikes on its interests in Syria. On April 8, 2018, one of Israel’s recent operations reportedly destroyed an Iranian Tor-M1 short-to-medium range surface-to-air missile system at Tiyas Air Base, or T4, near the city of Homs.

In the end, regardless of whether the Russians did or didn’t ship any additional S-300s to Syria for its own forces or to deliver to Assad, the Kremlin clearly remains determined to protect its interests in Syria. It is visibly continuing to pour more materiel into the country, activities that run counter to Putin’s claims in December 2017 that Russia had achieved total victory and would be withdrawing the bulk of its forces.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com