The Russian Ministry of Defense has released its first official video showing a pair of Su-57 stealth fighters during their bizarrely short deployment to Syria earlier in 2018. It’s as unclear as ever what the planes actually did in the two days or so that that they were there and whether they flew any actual strikes, but the threat of attacks on Russia’s Khmeimim Air Base may have cut the entire affair short.

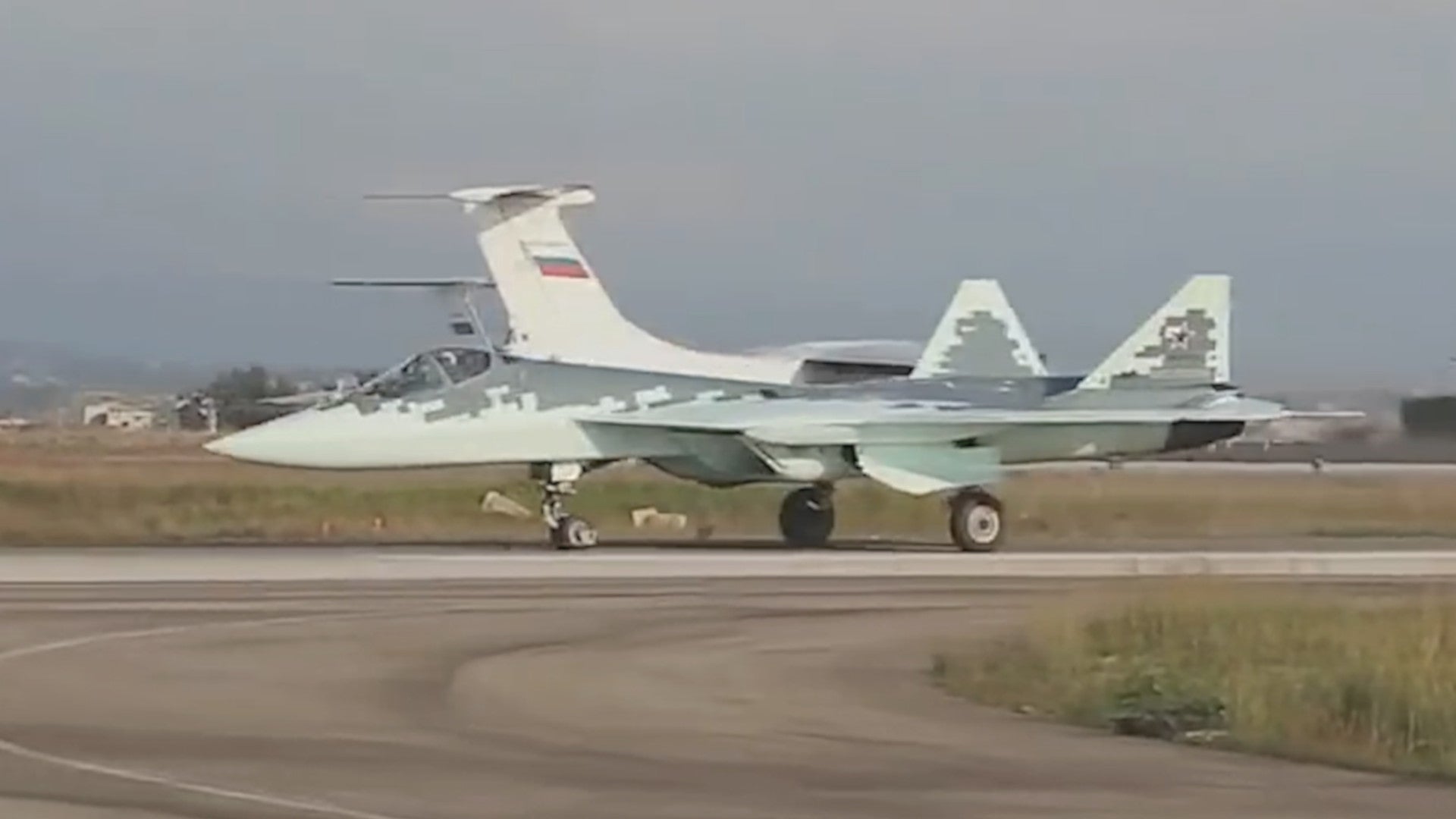

Russia’s Defense Ministry posted the video montage online on Nov. 19, 2018. The clips show the Su-57s landing and taking off from Khmeimim in Syria’s western Latakia governorate, as well as in mid-air against solid blue skies with no discernible landmarks. The jets arrived in the country on or about Feb. 23, 2018, and were officially only there for two days, but we don’t know if this means approximately 48 hours in total, two nights, or some other exact length of time. Russia now says the aircraft together flew “more than 10 sorties” in that time, which would average out to more than 2.5 sorties per plane, per day if the deployment period is accurate.

The sorties allowed the Russian Air Force to evaluate the Su-57’s basic flight performance, as well as the operation of its flight control, communications, and other mission systems, in a real combat environment and under extremely hot conditions, according to a statement from the Russian Ministry of Defense. The jets also reportedly got a chance to test their weapon systems, but it remains unclear if this means they engaged actual targets in Syria.

The video does not show either of the aircraft carrying bombs or missiles externally and there is no strike footage included among the clips. It is, of course, possible that the jets exclusively used weapons carried internally to strike rebel positions.

In May 2018, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu publicly showed video of a Su-57 launching what appeared to be a Kh-59MK2 cruise missile from its internal bay. He added that this test had occurred in February 2018, but did not clearly indicate whether or not it had occurred in Syria.

If the main objective of the deployment was to evaluate the capabilities of the Su-57 employing the Kh-59MK2 against real targets, it could help explain its brevity. Otherwise, it remains as difficult as ever to see how the Russians could have garnered any meaningful amount of data on the aircraft’s broader performance and other attributes in just two days.

There is also the possibility that the Kremlin intended for the Su-57s to spend more time in Syria than they actually did in the end due to security concerns. By Russia’s own admission, Khmeimim had experienced a number of attacks by small drones since at least 2017. Then, in January 2018, the base suffered an unprecedented mass drone attack that only seemed to escalate the situation.

Satellite imagery both confirmed the Su-57s had deployed to Syria, but eventually also showed at least one inside an impromptu revetment, suggesting the Russians were particularly concerned about the potential for damage to the aircraft. The size and layout of Khmeimim has long forced the Russians to park tactical aircraft very close to each other on the aprons, increasing the risk that the destruction of one jet could lead to serious damage to others nearby.

The drone threat has persisted since then, with Russia claiming that there had been an increase in rebel use of small unmanned aircraft in August 2018. The Kremlin has also accused the United States, among other foreign opponents, without providing any evidence, of supporting the militants and their drone operations.

In addition, earlier in November 2018, Viktor Murakhovsky, military expert and editor-in-chief of Russia’s Arsenal of the Fatherland magazine, also claimed in a social media post that his sources had indicated that the Pantsir-S1 point air defense system had been virtually worthless in defending Khmeimim. He said that between April and October 2018, the vehicles, which have a combination of radio command-guided surface-to-air missiles and a pair of 30mm automatic cannons, hit less than one-fifth of their intended targets. In the same period, the Tor-M2U short-to-medium range surface-to-air missile systems at the base had an 80 percent hit rate.

Murakhovsky has since deleted his post, possibly under pressure from Russian authorities, but there has also been no further confirmation of his claims. If his assertions about the capabilities of the Pantsir-S1 against small drones are true, it could point to even greater risks to Russia’s aircraft, other assets, and personnel at Khmeimim than had been previously understood.

Losing a Su-57, or otherwise having one suffer major damage, at the hands of small, homemade rebel drones would have been especially embarrassing for Russia, where President Vladimir Putin has claimed total victory over militants in the country more than once. Putin easily won a particularly controversial re-election bid less than a month after the stealth fighters returned home unscathed.

On Nov. 18, 2018, Russia’s Television Zvezda, the Russian Ministry of Defense’s official television channel, released the second “chapter” of its Russian-language profile series on the Su-57, which also includes various footage of the aircraft, though none apparently from Syria.

The danger of small drones continues to be a major issue for Russian forces, both in Syria and in general. As with other countries

around the world, the Kremlin has realized the seriousness of the situation and is making training to defend against mass drone attacks mandatory for all units.

It may have also prompted Russia to begin building reinforced concrete shelters at Khmeimim to help shield against future attacks. Satellite imagery that the Atlantic Council think tank’s Digital Forensic Research Lab obtained in November 2018 shows the construction in progress along base’s main flight line. The Russians have also installed other, less permanent open-topped revetments to protect various tactical aircraft.

Closed-top shelters will also make it more difficult for observers to gauge the size and composition of Russia’s air contingent in Syria. This may enable the Kremlin to claim it has or is in the process of making good on its many pledges to reduce its force posture in the country without having to actually do so.

It could also help conceal the deployment, or length thereof, of more advanced aircraft, such as the Su-57s, in the future. The shelters themselves, of course, only add to the existing evidence that Russia has no real intention of significantly scaling back its activities in Syria any time soon.

With the new shelters in place, the Russians may even decide to send some of their Su-57s back to the country for a more extensive and realistic combat evaluation.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com