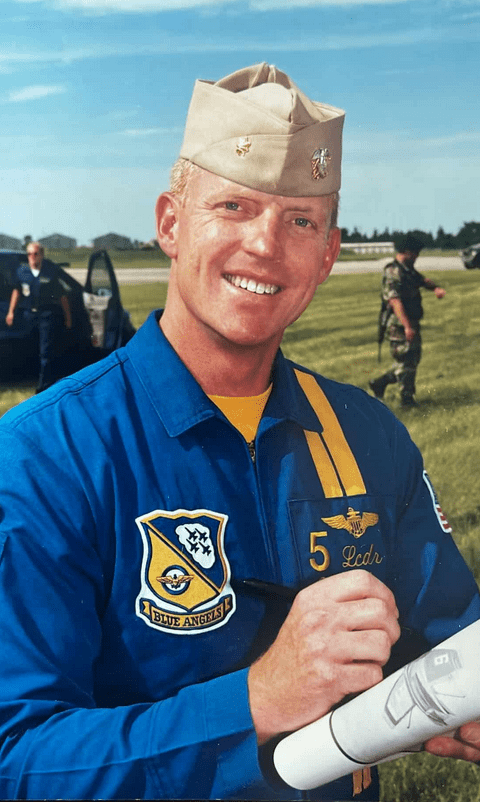

Scott “Intake” Kartvedt has had a remarkable flying career that is still very much evolving. Spurred by seeing Top Gun in theaters as a kid, Kartvedt joined the Navy with dreams of flying fighters and did exactly that. He went on to become a Blue Angel, took his Hornet squadron to war twice, was the first commanding officer of a Navy F-35 squadron, and has gone on to fly some of the most dynamic stunt flying scenes in Top Gun: Maverick. So yeah, “Intake” has his fair share of stories to tell and insights to convey.

With that in mind, Scott decided to write a book. Titled Full Throttle, it takes the reader through his flying adventures and all the lessons learned from them.

The War Zone sat down via Zoom with the accomplished aviator and leader to discuss a very wide range of subjects — from the F-35 to the future of unmanned naval aviation to the making of Top Gun: Maverick. And just as we thought, Scott’s perspective didn’t disappoint.

Let’s launch into it:

Tyler: Let’s start out with Top Gun. What a legacy both in the Navy, among the global combat aviation community, and in popular culture. Top Gun got you into Naval Aviation, influenced your career as a naval aviator, and eventually brought you into the fiction side of it as a stunt pilot for Top Gun: Maverick. That’s quite the journey. From A to Z, right? Can you talk a little bit about this crazy Top Gun thread that sort of helped define and bookend your career a little bit?

Scott: It’s interesting that I wanted to go to Pepperdine and be a business person and get into real estate, but I saw Top Gun in my senior year in high school in May of 1986. Like so many people of my generation and my age, it was inspiring and it was something that was exhilarating… You had only seen anything like it in World War II, Korean, or Vietnam type of movies, and now here’s this F-14 getting launched off an aircraft carrier. It was just so intriguing to me.

My best friend and I decided that we were gonna be fighter pilots.

We told all of our friends, the boisterous exaggerations of an 18-year-old, and we both went to college and at the end of college we decided to join the service. He went into the Air Force. I called up the Navy recruiter and said, “Hey, I wanna go and fly airplanes off of ships.” He said, “So does everybody.” And I said, “Yeah, I think I can do it.”

So that’s what started the journey.

I subsequently ended up getting into the Navy and being fortunate enough to fly fighters. And then, as you mentioned earlier, Tyler, it’s full circle. I mean, 33 years later, almost to the month, I end up flying as a stunt pilot in Top Gun: Maverick as one of very few civilian stunt pilots flying in that movie.

I pinch myself to remind myself how fortunate I am.

Tyler: Did you attend the Navy Fighter Weapons School when you were in the Navy?

Scott: No, I didn’t. So that’s a great question. I didn’t end up going to Topgun. I was an F/A-18 instructor at Marine Corps Air Station El Toro and then subsequently followed on to Miramar. I was a landing signal officer teaching Marines and Navy pilots how to land on the aircraft carrier day and night and my path was the Blue Angels. So at that career junction, if you choose to take a path, you either go the test pilot route, the Topgun Weapon School route, or the Blue Angels. So, and I applied and was accepted to the Blue Angels.

Tyler: It seemed like that was a good choice based on what you did in your career later on.

Scott: The crazy thing is, and I’ve got friends who have been the commanding officer of Topgun or have been instructors there, and so it is not lost on us that I didn’t go, but because I went to the Blues, I was fortunate enough to fly in the movie to represent all of the Topgun instructors.

Tyler: What scenes did you do in Top Gun: Maverick and what was involved with them? And what were you flying?

Scott: The part that Randy Howell and I flew was the scene where Maverick and Rooster steal the F-14 at the end out of enemy territory. Randy and I flew that entire… From that moment all the way till the end where they crash land the F-14 on the aircraft carrier. Clearly, we didn’t crash land an F-14 on an aircraft carrier, but all of the fighting through the canyons with the big granite walls, out over the ocean where Hangman, the actor Glen Powell, comes and saves the day, Randy and I did all of that flying.

So we would show up in the morning, they would give us the storyboard to show us what ‘image’ they wanted to capture, and then we would determine with the cinematographer, Kevin LaRosa, or the aviation stunt coordinator, how we would get that shot and how we would make that come to life. And then we would go film it. So some days I was Maverick, some days I was the bad guy, and it just depended on what we were filming that day.

Tyler: And you were doing this with L-39 camera ships or should I say surrogates?

Scott: Yeah, surrogates is a great term. So we flew L-39 airplanes that are owned by the Patriots Jet Team — great 2-place trainers. All the flying was real, I can assure you, because it was really dynamic flying, but just like a video game, they basically just put a skin over the airplane to make it a Tomcat or an Su-57.

Tyler: That must have been some pretty intense flying, considering what we saw. The low-level stuff, in particular. Even for somebody like you, with all your experience in fast Jets, that was at least to me as a viewer when I saw it on the IMAX, that was pretty down in the weeds, it seemed like. Some very tight maneuvering.

Scott: Yeah. Tyler, I having gone to Iraq for three tours, Afghanistan for two tours, so five combat deployments, flying with the Blue Angels for three years. It was equally as intensive as any of those. Because in order to make it look right, the airplanes have to be really not… To make it look dynamic, the airplanes have to be really close. You’ve gotta be exceptionally low to the ground. And if you go back and watch the movie in that final eight minutes, we’re flying under Kevin when he’s in a helicopter and his helicopter is at 50 feet off the ground. We’re flying under it, so we’re trying not to hit the trees, not to hit the helicopter, not to hit each other, flying through each other’s jet wash.

It was very, very dynamic.

Kartvedt)

Tyler: You blazed a real trail bringing the F-35C into an operational reality for the Navy as the commander of VFA-101, Grim Reapers. That was the first F-35C squadron for the Navy, down at Eglin AFB. What really went into such a massive undertaking? What were the biggest hurdles? And obviously, that aircraft during that time period had tremendous controversy. I’m sure there was pressure to get it where it needed to go. What was that experience like?

Scott: Yeah, the challenge. So I worked in the Pentagon originally as the Requirements and Procurement Officer for the F-35, which is how I got involved with F-35. And at that point, it was massively delayed. A lot of the challenge, the original concept from a design perspective was compatible components between variants, so the A, B, and the C. And then what they found was from a security perspective, there were nine partner nations. All of them had different levels of security that they wanted, or country-specific security features with the airplane.

So what we ran into in the F-35 training centers, I was running the F-35C training squadron, was what if the Israelis came through our training, which they would have to do, but they were going to fly a U.S. F-35C? So it’s an American airplane with an Israeli pilot. And if the Brits would have bought Cs, what if there would’ve been a British instructor instructing an Israeli pilot? I mean, you have all these country challenges. So you multiply that out by nine partner nations. With the A variant, it was astronomical the challenges, because you could have a Korean student in a Turkish airplane being taught by an American instructor, and how do you protect each nation’s security features within the software? That was a challenge.

And probably the biggest challenge — I don’t know how they ever resolved it. I retired in 2013, but those were, that was the biggest challenge we were working through at the time. Not only the security piece, but the liability you had, because they were centralized in the training centers in Eglin, depending on the variant of airplane we were flying. Foreign student, foreign airplane, U.S. soil, and liability issues were a concern too.

Tyler: How, in your opinion, has the F-35C changed naval aviation, not just when you were in, but since then? What’s the feedback you’re getting about the aircraft and how it’s doing in the fleet?

Scott: It has remarkable capabilities. It is exceptionally behind timeline. The size of the engine and the heat signature of the engine is a bit of a detriment to encountering infrared-seeking defense systems. So I think it was delivered late and it would… It allowed many enemy air defense systems to catch up to, I don’t wanna say the stealth technology, because the stealth is radar, but that giant engine creates a pretty big heat plume that can be seen easily.

It has a great electronic attack, electronic protect suite. It has additional capabilities that they’re still discovering and what it can do to integrate strike fighter operations. It’s just a shame that it took so long for it to materialize.

And then the commonality piece — it didn’t really play out. I think that became exceptionally cumbersome. The Air Force has different requirements. The Marines have different requirements. The Navy has different requirements. To build an airplane that they try to make meet all of those requirements is a little bit of a ‘horse designed by committee is a camel,’ right?

Tyler: I think that lesson learned has been internalized openly now by recent leadership in the Pentagon. I think they realize that there were mistakes made that they’ll never do again, or hopefully they won’t. Obviously, the B model aircraft having a STOVL capability is a huge tax on the A and C variant forever, no matter what you do to it, it’s still going to have those compromises.

Scott: Oh, but definitely. Yeah. Unbelievable. Just from a weight perspective. And then you talk about an internal gun vice an external gun, and some services wanted the gun, others didn’t. I think the original cost, and I have a document from when I was in the Pentagon when Defense Secretary England signed because it was going to save money… They were gonna be able to make it for $30 million a piece. But because of all of the reworks and compromises when I left it was over $160 million per plane.

Tyler: Right. But it’s come down significantly.

Scott: Well, the cost of the plane may have come down. But the logistical hub and spoke methodology from maintenance from Lockheed maintenance still creates challenges.

Tyler: And that’s exactly what I want to get into next. You were in there when these planes were really new. The reworks were happening constantly. There were differences in block to block, and sub-block. The operational costs was very horrendous during that time and I know a lot of the jets weren’t flyable. The availability rates were quite low. With a new airframe that’s understandable to a certain degree. Did you see that as you were moving through your time with the F-35C and as you watch now from the outside have are you seeing that getting better?

Scott: I’m not sure how much better it got, but I can tell you the challenges that we faced back, logistically specifically, it was designed to be maintenance on demand, essentially. So the aircraft could relay a message to the supply warehouse and say, this part is getting ready to fail. And then Lockheed could send that part out to the base and it could be replaced, rather than having to have large warehouses full of supply parts, not knowing which was gonna fail and what you might need. You take that into the maritime service and the challenge, Tyler, is that you can’t logistically operate that way because we could have a ship, in this case, off the coast of Taiwan that needs a part, and Lockheed Martin can guarantee its arrival into Okinawa. But now there is no FedEx, UPS, DHL that’s gonna get it out to the aircraft carrier. So it stops and now you have a delay and it has to go get picked up and the aircraft might be down. I don’t know if they have resolved that challenge…

Tyler: Yeah. It remains, just this year, one of the top challenges of the program.

Scott: There’s no doubt about it.

Tyler: They’re working now to change that, but that’s very interesting that your experience was very much the ghost of F-35 future, to a certain extent.

Scott: Oh for sure.

Tyler: They’ve kind of come to terms with reality that that looks great for maybe commercial aviation, but for combat aviation, there are definitely some major, major issues, and not even factoring in during a time of actual war in a contested environment as you just described.

Scott: Yeah, right. I think you could break it down into the difference between shore-based and sea-based aviation. The challenges are significant.

Tyler: Let’s talk about being a squadron commander. You had two runs at this job. You were CO of a Hornet squadron and then you had the F-35C posting.

Scott: That’s correct.

Tyler: So you had two times at bat. Just as an observer and interviewing a lot of people over the years, the stress and stakes involved with that job are absurd. It’s incredibly intense. You almost have to compartmentalize yourself out of it, because it’s a lot. It takes a certain individual. But it’s also steeped in legacy and history, that particular position. And even in, once again, pop fiction. I mean, in our sci-fi movies and everything else, squadron commander is a unique and coveted position, leading your team potentially into battle.

What makes a good Navy fighter squadron commander?

Scott: Right off the bat, my answer would be the ability to recognize that each and every sailor in the unit has a purpose and they need to be valued. So I viewed my particular role as the commanding officer, not only to be, you’re 100% accountable and 100% responsible, but I trusted and valued our sailors for their opinion, and I was willing to listen to them and treat them as adults, and I think that, that was very beneficial. We won a lot of awards, and I think it’s because I was very transparent, treated them as the warfighters that they were. And if we had a problem, I would ask them what their solution was, rather than think that I was the smartest all-knowing person in the unit. Because there were experts in different fields and it was absolutely critical to have their knowledge.

Tyler: And how does that change taking that type of unit into combat as a commander? There’s so much responsibility in peacetime. There’s so much stress in that job. How does that change when all of a sudden you have to employ all those skills that your unit has learned and sometimes those lessons were learned in blood. I mean, it’s already a dangerous business.

Scott: Yeah. So you can’t beat the safety drum enough. But our value statement, if you will, was people, professionalism, mission. And this was back in 2008, ‘9, ’10. And at the time, because we were still very hot and heavy in combat operations, I had a lot of people that would say, “You can’t put mission last, mission has to be first. You have to accomplish the mission.” And my argument has always been and remains to be that there is no mission if you don’t have the people, so the people have to come first. In fact, I would make the argument that it could be people, people, people, because they are the lifeblood of any organization.

So where that really came to fruition, we were deployed for six months, came home for four months, and then went back out for another seven months. There was tremendous stress on the families that remained behind. So I asked the squadron to come up with a solution to maximize the time at home, so that the entire goal before our second deployment was to ensure our sailors were, one, refreshed, and two, motivated to go back to sea.

We came up with a plan that enabled us to do that. And again, the sailors felt valued, respected, the family members did too. We got on the pier in January of 2010 to go back out to war after only a short four-month break post-holidays, our sailors were whistling coming down the pier, getting ready to go up the gangplank to get on the ship, because they were well-rested.

Tyler: What a difference culture makes, right?

Scott: It was unbelievable. Absolutely unbelievable. Just really quick, what we did is — it was over the holidays. Anytime you load aboard the ship, there’s always a panic to load, and you’re working the last two or three days before you deploy. And that happened to be over New Year’s, and to work three days before you leave for six months just seemed like a really bad idea. So we recommended to the carrier air wing commander that we were going to load up before Christmas. We were going to have everything on board. We were going to shut down for two weeks before we deployed, and take from Christmas all the way to New Years off. And then we were going to walk onto the ship refreshed and ready to go. And he said, “There’s no way that’s gonna work. You can’t do that. We’ve never done that.” And I said, “Oh, it’s absolutely gonna work.”

I put it back on the chiefs and the sailors and said, “You tell me how to do it. And we together will be accountable.” And so we loaded everything, packed out pre-Christmas. Everybody had a solid ten days at home. They got kissed by their family members on the pier, and they were ready to go. And most of the other units and sailors were really pissed because they’ve been working over New Year’s.

Tyler: And then a back-to-back deployment like that.

Scott: Yeah. And so they were happy. And we ended up winning the Battle E Award, the Michael J. Estocin award, the Safety S Award. And there was, what I would call customer service up and down the chain.

Kartvedt)

Tyler: What was your most memorable combat mission? Was there one that stood out above anything else?

Scott: I think you remember all the ones that you employ [expend ordnance] on. The most memorable was the troops in contact near Kandahar. Myself and a wingman named “Simple Jack” had got called in. The Joint Tactical Air Controller on the ground had read us the nine line [briefing on the situation/targets] as soon as we had checked in, and given us clearance to employ, before we even had eyes on. You could hear the machine gun fire in the background. It was approaching dusk. We were running low on gas. The special forces team was pinned down… They were basically in a canyon pinned down by a high point to the north and a high point to the south. So we employed on both of those with bombs. Then we were asked to re-engage on those positions with the 20 Mike Mike [20mm], the high explosive rounds from the machine gun, the Vulcan cannon. There was a Dutch helicopter that was firing on the ridge line, and we were shooting machine gun fire. It was very dynamic, very fast-paced. We were low on fuel. We had to coordinate a tanker to come get us, because we had to stay and support these guys.

The good news is all of the coalition forces survived and the enemy had a less-than-stellar day.

Tyler: Let’s move to the Blue Angels. That job has to teach you things that even the most experienced fleet naval aviator hasn’t learned. What were the biggest takeaways as an aviator from your time with the Blues?

Scott: Well, I think that initially, the idea is you get to do this ‘flat-hatting,’ to use like an air show term. But there’s no need to flat-hat, right? And the respect for the maneuvers that we are doing, the respect for each other, and really the attention to detail. So right from the very get-go, you start the placement of your hat, talking to somebody without sunglasses on. And the standards are set so high… From the way that you wear your uniform to the way that you fly, but foundationally, all 150 personnel on the team meet those exceptionally high standards. And we used to say that Delta always comes first, which means we will do whatever it takes to get six airplanes in front of the crowd, to represent the professionalism of our sailors and marines that are forward deployed and serving, because anything less than that isn’t good enough.

So the attention to detail, the caring for each other, the discipline… It’s all small things.

Before each brief and before each debrief, we would always shake hands with every single person in the brief and every single person in the debrief. And the subconscious benefit of that is, that we are human beings, we are in this together as a team. And whatever happens professionally, we will debrief at the end, but we’ll learn from it. It’s not personal, it’s just professional.

So when I left the Blue Angels, every organization I went to, to include where I am now, we shake hands upon greeting and upon departing. And at first people think, ‘God, this Scott sure shakes hands a lot.’ But then they realize that it’s that literal physical connection that we are in this together, that’s exceptionally unifying.

Kartvedt)

Tyler: Solo is the best deal on the team, right? The solo five and six positions? There’s no better position than the solo position, right?

Scott: The solo pilots certainly think so.

Tyler: You get the sneak pass and all that.

Scott: There’s a genuinely fun rivalry between the diamond pilots and the solo pilots. The diamond pilots would let you know that they are the show, and the solo pilots are just the filler. But the solo pilots, we call it the ‘solo mafia,’ five, six, seven, and eight, as opposed to the diamond, each position is intense and demanding in its own right. The solo pilots just get to go a little bit faster and pull a little bit more G.

We used to always say that we were the rock stars of the show. So it made it a lot of fun. Obviously, as you get older, you realize that just to be on the team was exceptional. But when you’re ripping down Lake Michigan, 20 feet off the water, creating a wake behind you at 0.99 Mach, that’s a pretty rock and roll, if you will.

Tyler: What’s the most enjoyable moment you’ve had in the cockpit, and what’s the most terrifying?

Scott: Most enjoyable time… Specific to the Blue Angels or overall at large?

Tyler: Overall. Full career.

Scott: Yeah. It’s interesting. The first thing that comes to mind initially was on the Blues. We were flying over Lake Michigan. It was the Chicago Air and Water Show in the late summer of 2002. And the weather was perfect. I was the number five pilot. My best friend Dan Martin was the number six pilot. And we had grown very close and there was one maneuver, it’s a six-ship maneuver, so a Delta formation maneuver and we break out. Dan and I are inverted and I’m looking at him inverted, and he’s cutting across the Chicago skyline. I just remember thinking in that moment, “I will never get to do this again” and how fortunate am I to have had this opportunity. It was surreal to the point that flying back to Gary, Indiana, at the end of that show, I actually literally shed a tear, because it was that overwhelming to be one of so few that had the opportunity to do what we did, from the Blues perspective.

From a combat perspective, I wouldn’t even relate it to a flight. But coming home after the last deployment in ’13 of 17 months of combat operations and bringing home every sailor safely, was a remarkable accomplishment that I’m very proud of. I get a lot of attention for the time that I did on the Blues, because it’s a very public relations-oriented team. But what I am most proud of is the combat tours and the sailors that I served with, because we had a genuine purpose that we were all committed to.

Scariest moments? January 16th, 2001, learning a new maneuver with the Blue Angels. We got very, very close to the ground in a very harrowing instance. May 10th, 2002 another harrowing — a very close call in Peoria, Illinois at a practice show with the Blues that was a finger snap away from ending it all. Those were two exceptionally dynamic events that every once in a while I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and go, “whew.”

Tyler: Let’s talk a little bit about the changes with the Navy. Carrier Air Wings will be dominated by unmanned aircraft in the decade to come. Roughly 60% of the air wing in the mid to 2030s we’re hearing, something like that. And it could be much more depending on how this all works out. How do you see the unmanned component working with the manned component and the impact that could have on the culture of naval aviation?

Scott: I think there’s definitely an element and some capabilities that unmanned provides, as we have proven during the 20 years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan, that provides great capability. I cannot, for the life of me, understand how they will have more than one or two unmanned types of vehicles on an aircraft carrier. I don’t know how you transition it from flying to landing on the deck and transitioning it to taxing on the deck. So the reason I say one or two is because you would have to… I could see how a tanker would be super beneficial, overhead, flying very slow, burning very little bits of fuel so it could refuel the fighters. But the dynamic aspect of landing on a carrier and then parking that airplane on the carrier, I conceptually can’t understand how you could do that with a drone or a remote controlled vehicle, based on the proximity that the airplanes are placed to each other. Clearly it can happen and it will in the future. But I think you had said 60% of the air wing in 2030. I don’t see it.

Tyler: 2030s, yeah.

Scott: Yeah, I can’t, I don’t see that. I see more of the tanker, support type of airplanes that can land after the rest of the fighters do.

Tyler: The landing and launch recovery cycle issues are clearly one of the biggest outstanding issues I think with the concepts they’re looking at.

Scott: Yeah.

Tyler: And then on the cultural side, any thoughts on that?

Scott: Naval aviators, especially those carrier-based aviators, I like to think that they’re a different breed, because it’s a very dynamic environment. And when people say you land an airplane on a ship, you’re crazy. I don’t think we’re crazy. I just think we’re different. So culturally, that could change. I am sure the same way that unmanned aerial vehicles in the Air Force has created a bit of a change. But we adapt and overcome and move with the times. And I’m just glad — as I’m trying to think about this, and not even from a political standpoint — I’m just really glad that I had the opportunity to earn my wings of gold, and when I did and have the opportunities that I did.

Tyler: There will be less of them.

Scott: Yeah.

Tyler: That’s just the reality. There will be less naval aviators in the future.

Scott: Yeah. And I guess where I’m going at it, there are unmanned aerial vehicles, and so there are pilots flying unmanned or controlling unmanned aerial vehicles from the carrier on the ship. Do they wear a different set of wings? Do they get a different warfare specialty insignia? That’s a fight that I won’t be a part of, but it will be one.

Tyler: Probably lucky you’re not. Let’s move to landing on carriers. You learned how to do it. You taught pilots how to do it. You did it hundreds of times yourself. You’re responsible for young people going out for the first time to help them to learn that skill set. What do you think of the potential changes now where a newly winged naval aviator will not see the boat until they arrive at the fleet replacement squadron, and they’re going to be basically getting into a Super Hornet or an F-35C the first time that they actually go and land on a carrier.

Scott: Yeah. So one, that’s a great question. Two, it’s exceptionally personal to me because both of our sons are carrier pilots.

Tyler: I didn’t know that… Congratulations, followed in the old man’s footsteps! Good for you.

Scott: Yeah, exactly. Our oldest son is flying F/A-18s, and he went to the boat in the T-45. And, clearly I think you need to be able to manually bring an airplane aboard the ship because as we prove time and again, the systems can fail. When they do, you need to have the foundational skill set to do it. So I’ve had lots of conversations with my peers on this, and I could see how you could save a bunch of money by not doing it, and you could certainly train at the field in the simulator to get the skill set. My concern is not whether they go to the fleet replacement squadron and get trained and they go to the boat the first time in the Hornet. My concern is an over-reliance on the Magic Carpet and allowing that to become a crutch, rather than teaching the foundational skills of meatball, lineup, angle of attack. Because it’s not a matter of if it will fail, it’s when it will fail. And when it does, you still need to be able to fly the meatball all the way to touchdown on center line and land on that ship regardless of the sea state or the conditions.

They brought up the Magic Carpet stuff that’s going on, and now it’s becoming not a tool, but the primary means of operations, and worries about that. Especially in a combat scenario. I’ve heard that over and over again.

Yeah. You know, it’s recently as the F-35C that crashed… I think it was on the Vinson… My understanding is that, it didn’t know that it was supposed to land so it didn’t intercept the Magic Carpet. And the pilot that was flying didn’t intercede because they had always expected it to work.

So that’s exactly what I’m talking about. It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when. So that cost $160 million to replace that airplane and thank goodness the pilot was okay, but that $160 million could go to a ton of foundational training for pilots.

Tyler: And it could have been much, much worse. If it hit just a little differently on that deck… It could have been horrific.

Next Generation Air Dominance. This is the Navy’s big deal, a top priority right now. The next manned tactical aircraft backed by the unmanned stuff we were just talking about. Also, this is very focused on the Indo-Pacific and the China problem. What would you want in a next-generation manned tactical aircraft for the Navy?

Scott: The ability to go high and fast with stealth weaponry so that you could launch off of the carrier from a safe distance, from shore, get the airplane up high, because the higher you are and the faster you go, the longer the stick of your weapon is — the farther you shoot the arrow, right? So I was making a push in the Pentagon back in 2011 with the F-35 that we didn’t need stealth fighters. We needed stealth weapons. I don’t need the fighter to go into enemy territory. I need a long-range weapon to go into enemy territory and be undetected. So if I can launch it from a high and fast platform safely from the sea and send that down range with velocity in a stealth case, I can do some good work. So that’s where I would lean.

Tyler: The Patriots jet demonstration team is a really unique organization. They have their hands on a lot of things. The Top Gun filming, for instance. People don’t realize they do so much more than the air show side of things. What is the biggest difference being in that team compared to the Blue Angels?

Scott: That’s a great question. So that’s a fascinating switch from Indo-China to the Patriots, but the Patriots, is a truly a great joy for me. So former Thunderbirds, former Blues, exceptionally talented pilots, I’m the youngest guy on the team. The beauty of it and the commonality between the Blues and the Patriots is the trust and respect that we have for each other. And that goes without saying. The skill. set, because we have been trained the way that we were, we have that ability, we have the skill sets to fly the airplanes. But it’s a great team, it’s all volunteer, everybody wants to be there. So we have a great admiration for everyone on the team, from the maintenance personnel, through the narrator to the pilots. It’s truly one of my greatest joys.

It can be intense. We’ll go fly San Francisco Fleet Week here in about a month and we will have not flown in two months. So because of our age, we will be very anxious and we will be very cautious and very safe. Then as soon as we get airborne and we join up with each other, we’re right back to riding our bicycles and we go into a loop and it is awesome.

Tyler: It’s a great show. It’s always enjoy it.

Scott: Oh, thanks.

Tyler: The Navy that you were in, obviously gave you so much. It gave you so much and you gave it so much. But no institution is perfect. And a guy like you, who’s done all these things, probably there’s a few things that you think, “Hey, that could be done better by the Navy.” Specifically in naval aviation, where do you think there’s opportunities to improve?

Scott: I think this goes true with any organization and certainly the Navy. You’ve gotta hold the standard high. When people can’t achieve that standard or are unwilling to achieve that standard, let them go. But don’t reduce your expectations and standards of what you want to accomplish tactically operational and strategically, because you are trying to accommodate someone who either doesn’t have the capability or is unwilling to improve.

So in Naval aviation flying around a ship at night in a fighter can be dynamic and not everybody can do that. And I’m not saying I am better than anyone, the best way that I can explain it is, I don’t have the physiological capability to be a linebacker in the NFL. I will never be one. I don’t have that makeup, but the talents that I do have are to fly an airplane and think fast. So don’t force people into doing something that they don’t have the capability for, or maybe really don’t wanna do. That’s why I say, “Hold the standard, and hold people accountable to achieve that standard. And if they can’t thank them for their time and service and move on.”

Tyler: Let’s talk unmanned aerial phenomenon (UAP). Navy pilots specifically are seeing weird stuff in the sky. What are your thoughts on all that? And have you seen anything weird in the thousands of hours you have spent in the sky?

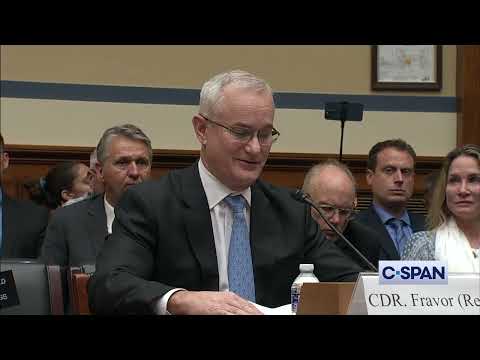

Scott: Yeah, sure… No, I have never seen anything specifically that made me think that it was a UAP or UFO or whatever term you choose to use, and I used to think that it was ridiculous. But Dave Fravor, one of the very well-known UAP identifiers who was in an F/A-18 and used the forward-looking infrared system — and I’ve seen the footage and it doesn’t make any sense to me — I know Dave and he is of sound mind and he is a good person that I have drank beers with. So I don’t discredit what he saw, what the story he has told. And so what I used to think, “Oh, it’s crazy, ridiculous.” Because I know Dave and I know he’s a credible, reliable, remarkable human being. I don’t know, I don’t have an answer. I haven’t seen it. But Dave has.

Tyler: You have done a lot so far in your life. Your next adventure was writing a book, Full Throttle. What did you want to accomplish with it? What was the goal?

Scott: My dad was a Submariner in the Navy and I would come back and I would tell him stories about flying in naval aviation, and he would always say, “Scott, your stories are outrageous. You should write a book.” I never paid much credence to it, because I was just so busy living at the experiences that I was living. Then when I was fortunate enough to get asked to fly in Maverick and people kept saying, “Scott, how did you get to do that? Why did you get to do it? How did they pick you?” I gave a presentation on it once, I got asked to give a speech and I said, “What do you want me to talk about?” And they said, “Well, tell us how you’ve been able to do the things you did,” and I’d never ever thought about it.

So I sat down for a long time and thought about: why have I been able to fly for the Blue Angels, have successful combat tours, fly in Maverick, and be first Navy F-35 squadron commander? It really boiled down to I say yes to opportunity. I am willing to ask questions and ask for help, and I am not afraid to fail or make mistakes. So those three themes are weaved through the book, which really starts my senior year in high school to get into the Top Gun piece. And then takes us through 33 years later flying in Maverick and the life lessons learned, and answers the question of “how was I able to do that?”

The other interesting thing about this, Tyler, if you don’t mind me saying, a lot of people will say, “Well, you’re just lucky. You have been fortunate.” My mom tried to commit suicide twice in high school. My dad went bankrupt and foreclosed on our childhood home. The only reason I bring that up, it’s not because I’m any semblance of a victim, but when I talked to young people specifically, it wasn’t handed to me. I went out and I worked really, really hard and I committed myself to the goals that I had set. And I truly believe with all of my heart that if I can do it, then anybody can, and through the highs and the lows, but just keep moving forward towards your goals.

Tyler: You look at your resume and you’ve been a leader, you continue to be a leader. And even doing the book, it’s thought leadership. You’re getting that out there to inform other people what you’ve learned in your career. So if you could give one piece of advice to not just aviators or military people, but to just anybody on leadership and what you’ve learned, what would it be?

Scott: Don’t close doors on yourself, which is really the ‘say yes’ piece. Say yes to opportunity. The greatest list I can give is, I applied to be a NASA astronaut and all my friends said, “You’ll never be a NASA astronaut. You’re not a test pilot, you’re not an engineer.” And I said, “Well, NASA’s not gonna pick up the phone and call me.” So if I applied and they call me back and say, “Hey Scott, you’re not an astronaut.” No kidding, I’m already not an astronaut. So all they can do is say yes.

There are so many people that shut themselves down because they will say, “My teacher won’t let me do this, or I could never do that, or my boss won’t let me do this.” So they never even make the proposal or the proposition or the application. And that was really driven home to me when I left the Blue Angels and people would come up and say, “I wanna join the Blue Angels. How do I do it? I wanna apply.” I would sit and talk with them and drop a plan and tell them how to do it, and make recommendations. Two out of a 100 actually put in an application. So do it, say yes, assume the answer will be yes, because you have nothing to lose if you try.

I’m already not an astronaut.

Tyler: What’s the hardest leadership decision you’ve ever made?

Scott: I have to go with what popped into my mind first, which was leaving the military. It was by far and away the hardest decision, but we needed to make it together. Lisa and I, and it was in the interests of our family. So we opted to depart the Navy, even though, as you have mentioned, my resume was very ‘promotable’, if you will. We had to step away from that. And I don’t want to say start over, but transition into the civilian world. That was exceptionally difficult because there was a semblance of starting over and creating anew, but I don’t regret any of it in where we are, and what we have been able to do, and the success of our kids. So that was a very difficult leadership decision.

But that was specifically for the leadership of our family. I’ll tell you Tyler, when we sat down with our kids, we had two boys, they were in 10th grade and eighth grade, and I thought when we said, “Hey, guess what? Dad’s not gonna be a fighter pilot anymore.” I really thought that they were gonna go, “Oh dad, you have to.” The first thing my oldest son Wyatt said was, “Great, so we don’t have to move again?” My youngest son said, “So now we can get a dog?” So that’s when I realized that it really had nothing to do with me, but it was about us. Some of the hardships that they had endured, because they serve as well. So we moved to Colorado, made a final move, and got a dog.

That’s what we did!

Tyler: What are you doing now professionally outside of all your many other pursuits?

Scott: What I say my W2 job is I’m a pilot and instructor pilot for United Airlines. Really, really great company. I’m really involved in the human factors element of, how do we get people from all over the world to fly safely together in a flight deck, and holding the standards and the harmonization and the different behavioral traits that people have? How do we keep our passengers safe? That’s actually a passion of mine. So I work in the Human Factors Department.

And then on the side, in November I’ll be taking over as the President of the Blue Angels Foundation, we raise money to help prevent veteran suicide. I used to do corporate training for myself financially and now I do it for the Blue Angels Foundation, where we go and talk to corporate executives and their learning and development teams to help them establish cultures of excellence and standards and how they do that. All of those proceeds go to the Blue Angels Foundation to help prevent veteran suicide.

Those are my two primary interests. And then, you throw, the Patriots on the side, and then some occasional Hollywood work. I just did a commercial for Lay’s Poppables!

A huge thanks to Intake for taking the time to share his thoughts and experiences with us. Make sure to check out his website here and grab a copy of Full Throttle here.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com