The U.S. Marine Corps plans to put around 20 percent of its combined AH-1Z Viper attack helicopter and UH-1Y Venom armed utility helicopter fleets in long-term storage by the end of this decade. This is part of the service’s radical restructuring effort, known as Force Design 2030, which is scaling back or outright eliminating various traditional capabilities, such as the complete divestment of all of its M1 Abrams main battle tanks. The goal is to craft a more flexible Marine Corps with new capabilities, including various longer-range ground-based missiles and a greater emphasis on unmanned capabilities, that are better suited to the future distributed warfare concepts of operations that it is now developing.

The Marine Corps plans to remove 27 AH-1Zs and 26 UH-1Ys from service as part of Force Design 2030, according to a statement The War Zone received from the service’s top headquarters today. At least two AH-1Zs are already headed for the Boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona, as part of the inactivation of Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 367 (HMLA-367) at Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii. That unit is expected to stand down completely by the end of the 2022 Fiscal Year, as will Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 463 (HMH-463), as the Marines work to shutter all conventional helicopter units in Hawaii as part of Force Design 2030.

“As a result of Force Design 2030 squadron divestments, and pending final disposition, the Marine Corps expects to induct 53 H-1s (27 AH-1Zs and 26 UH-1Ys) into long-term preservation and storage,” Marine Corps Captain Andrew Wood, a service spokesperson, told The War Zone.

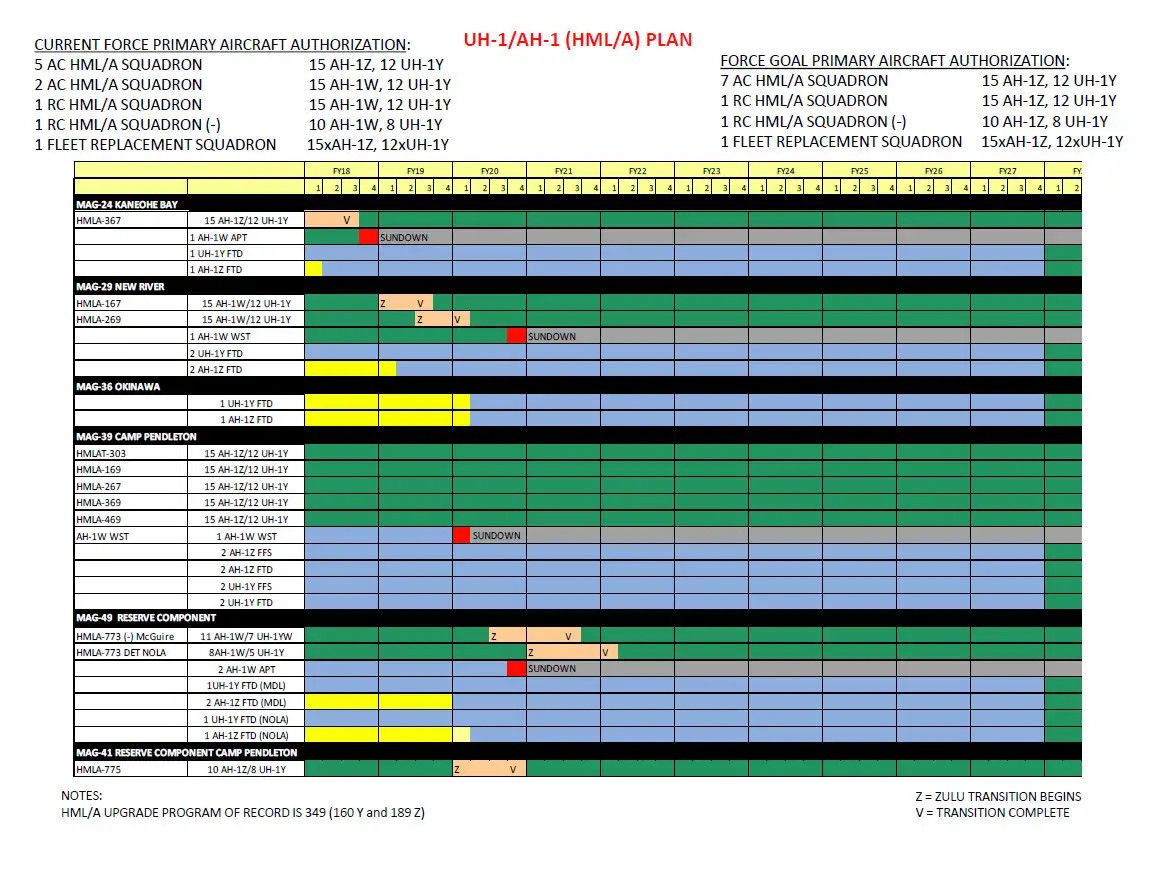

The exact size of the Marine Corps’ AH-1Z and UH-1Y fleets at present is not entirely clear. The 2019 Marine Aviation Plan, the last iteration of this annual report that the service has publicly released, said that the goal at that time was to have a total of 145 Vipers and 116 Venoms in both active-duty and reserve component units by the end of Fiscal Year 2022.

The service had fully completed its transition from the UH-1N Twin Huey to the UH-1Y by that time, but was still in the process of transition from the AH-1W Super Cobra to the AH-1Z. The Marine Corps got its first Vipers in 2005, but the service only declared it had reached initial operational capability with them in 2011. The first UH-1Ys that the Marines received are only slightly older. A number of AH-1Zs and UH-1Ys are also remanufactured AH-1Ws and UH-1Ns, respectively, a process that completely reset the airframes. Both fleets are, overall, still very young, on average.

The Department of the Navy’s 2021 Fiscal Year budget request, a public version of which came out last Spring and that also included requested funding for the Marine Corps, said the plan was still for HMLA-775, a reserve squadron, to swap its AH-1Ws for AH-1Zs during that fiscal cycle. That would have been in line with the 2019 Aviation Plan.

If HMLA-775’s transition to the AH-1Z was completed as planned in 2019, the only remaining question is whether HMLA-773, the other Marine Reserve light attack helicopter squadron, has received its planned complement of Vipers. HMLA-773 did fly the last official Marine AH-1W sorties last year as part of a ceremony marking the formal retirement of the service’s Super Cobras. The Marines have also said in the past that, as part of Force Design 2030, two entire HMLAs will be inactivated, only one of which, HMLA-367, has been publicly identified, so far.

Sending 27 AH-1Zs and 26 UH-1Ys to the Bone Yard would mean the Corps’ Viper and Venom fleets will shrink by around 18 percent and 22 percent, respectively, at least compared to the final totals outlined in the 2019 Aviation Plan. The combined “H-1” fleet, as the Marine Corps often refers to both types collectively, would be trimmed down by approximately 20 percent.

It is worth noting that the Marines say that the “final disposition” of these helicopters has yet to be decided. This could mean that it retains some of the airframes as sources of spare parts, or even in a more complete state where they could be more readily returned to service to replace losses from combat or accidents. Any helicopters it does ultimately determine to be excess to its requirements could be made available for transfer to other entities with the U.S. government, such as the U.S. Forest Service, which operates demilitarized ex-U.S. Army AH-1s to support aerial firefighting operations. They could also be transferred to U.S. allies or partners abroad. The plan is already to sell off all of the retired AH-1Ws.

There is the possibility that the remaining Marine light attack helicopter squadrons, or other activities, such as training bases, within the service, could receive some of these aircraft, as well. Two of HMLA-367’s UH-1Ys have already gone to unspecified units at Camp Pendleton in California, a major training and operational hub for the service on the West Coast, for instance.

However, the Marine Corps has made clear that it is looking to make permanent cuts to more traditional aviation capabilities as part of Force Design 2030. For example, the service still plans to eventually have 18 squadrons equipped with F-35B and F-35C Joint Strike Fighters, but the total number of aircraft each one of these units will have is set to be reduced from 16 to as few as 10.

“We may over time learn that 10 is the wrong number, it could be 11, it could be 12, I don’t know,” Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger, the service’s top officer, told reporters in April 2020. “But right now the target is good at 10.”

If the 53 “H-1s” that the Marines are planning to send to long-term storage end up being removed from service for good, it will represent a significant cut to its more conventional rotary-wing capabilities, especially when it comes to close air support and other armed missions. Both the AH-1Z and UH-1Y can carry various types of ordnance and the Venom can also be equipped with a version of the Intrepid Tiger II, a powerful podded electronic warfare system. Plans to give the Corps’ MV-22B Osprey tilt-rotors expanded arsenals that include forward-firing weapons have yet to become an operational reality.

At the same time, Force Design 2030 places more emphasis on unmanned platforms, including larger types, such as the MQ-9 Reaper, capable of carrying munitions. The Reaper has far greater range and persistence than the AH-1Z and UH-1Y, something that could also be found in future large drone designs. Other new long-range strike capabilities, including various ground-based land-attack and anti-ship missiles, are also part of the overarching force structure concept.

While something like an MQ-9, or even a much more advanced unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV), would not be able to completely replace the capabilities offered by either the AH-1Z or the UH-1Y, especially the Venom’s passenger and cargo carrying abilities, its extended reach would make it differently valuable for supporting future Marine Corps distributed operations, especially across the wide expanses of the Pacific. This is the argument the Marines have made for why they are closing out their conventional helicopter units in Hawaii. The service is now planning to send at least some number of KC-130J Hercules tanker-transport aircraft to take their place at MCAS Kaneohe Bay to support extended range MV-22B operations.

All told, the final configuration of the Marine Corps’ various combat aviation fleets at the conclusion of the Force Design 2030 process very much remains to be seen. Still, the new details about the service’s plans for AH-1Zs and UH-1Ys only further underscore that big changes are coming as the decade progresses.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com