A shadowy cat-and-mouse game between Chinese submariners and U.S. military forces tasked with tracking them is, by all accounts, increasing in scope and frequency in the Pacific. One stark example of this was recently highlighted by a Chinese newspaper’s report about a previously undisclosed incident in a highly strategic coordinator in the South China Sea that occurred on January 5, 2021, some details of which the U.S. military’s top command in the Pacific has disputed.

The South China Morning Post, or SCMP, which has its main offices in Hong Kong, published its initial story on the incident on May 15. The newspaper said the episode, details of which had emerged in a Chinese-language research paper written by a team that included members of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), had involved three unspecified U.S. “spy planes” engaged in a “hunt for Chinese submarines.” The researchers reportedly said that one of those aircraft had come within 150 kilometers (around 93 miles) of Hong Kong, prompting a significant PLA reaction.

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) confirmed to The War Zone that Chinese forces intercepted a U.S. Navy P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol plane twice in the northern end of the South China Sea on January 5, 2021. However, the command denied that this aircraft flew unusually close to Hong Kong.

After SCMP published its piece, The War Zone had reached out to INDOPACOM and the U.S. Navy’s 7th Fleet for more information. INDOPACOM is the U.S. military’s main command overseeing operations across the Indo-Pacific region. The 7th Fleet, with its headquarters in Japan, oversees Navy operations in the Western Pacific, including in the South China Sea.

“The U.S. P-8A that flew on 5 Jan 2021 was intercepted twice in international airspace between Woody Island and Hainan Island roughly 500km [just over 310 miles] from Hong Kong,” a spokesperson for INDOPACOM told The War Zone in a statement. “U.S. and allied aircraft routinely fly in international airspace to maintain situational awareness and reinforce international norms.”

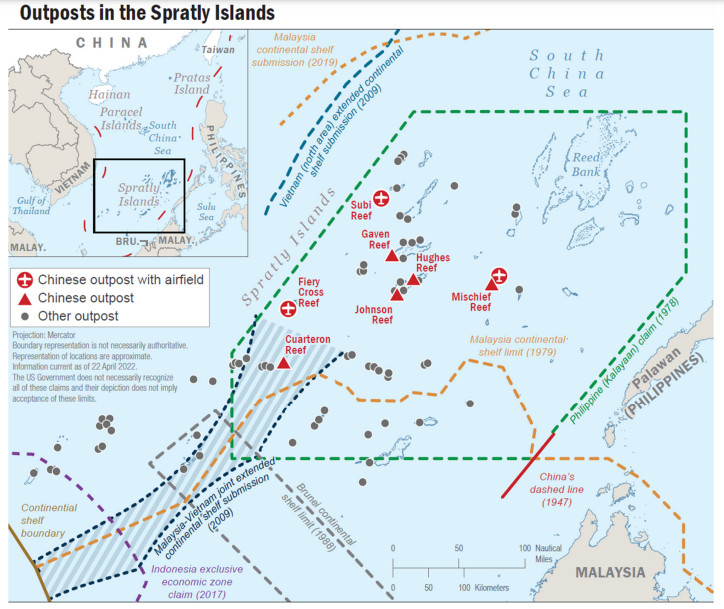

Hainan Island is home to a sprawling People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) base that includes large underground caves that submarines can sail in and out of, as well as a host of other Chinese military facilities. Woody Island is one of a number of island outposts in the South China Sea that the PLA has dramatically expanded in the past decade or so. That network of outposts features significant anti-aircraft and anti-ship defenses. This is part of a larger anti-access/area denial umbrella the PLA has established that extends from mainland China and covers this entire area. This would swing into action to prevent foreign military forces from moving freely in the region in a crisis scenario.

The area in between Hainan and Woody Island is also a key route for Chinese submarines moving in and out of the region. This includes the PLAN’s Type 094 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), all of which are based in Hainan. The U.S. military has previously assessed that the PLAN’s could operate those boats from the safety of “bastions” closer to the mainland, but recent analysis points to an increasing number of longer-range deployments. This creates new challenges for the already complex task of trying to keep tabs on where those and other Chinese submarines are at any time, which is critical information, especially when it comes to China’s SSBNs.

Most importantly, this geographical area culminating at the Luzon Strait, between Taiwan and the Philippines, is the primary corridor through which Chinese submarines based at Hainan Island, and especially the SSBNs, reach the greater pacific beyond the first island chain. As such, it is a critical anti-submarine and undersea surveillance choke point and China is very well aware of this as is the U.S. and its allies.

Back on January 5, 2021, what appeared to be two separate U.S. Navy P-8As were spotted using online flight tracking data in parts of the northern end of the South China Sea on or about January 5, 2021, based on online flight tracking data. Depending on one’s location, the Tweet immediately below may say it was posted on January 4, 2021. However, the time stamp shows that it was published on what was the following day in the region, which is to the west of the International Date Line.

Online flight tracking data at the time also indicated that a U.S. Navy MQ-4C Triton drone was operating in the area, and appeared to have flown closer to Hong Kong. “Although there was an MQ-4 aloft on 5 Jan 21, our records show it did not come within 150 km of Hong Kong,” the spokesperson for INDOPACOM also told The War Zone.

The Chinese research paper “said the PLA, which was conducting a naval exercise in the area, responded swiftly by sending out a counter force, the size and nature of which remains classified,” SCMP reported. “The two forces were so close that the U.S. military ‘self-destroyed’ its floating sonars to prevent the sensitive devices from falling into China’s hands.”

“The [research] team… said the US activities were a severe challenge to China’s national security,” SCMP’s story added. “According to the report, U.S. spy planes deployed sensors in waters near the Dongsha islands – also known as the Pratas islands – a group of atolls and reefs under Taiwanese control.”

The War Zone has so far been unable to independently locate a copy of this research paper, which was reportedly included in a recent issue of the Chinese-language publication Shipboard Electronic Countermeasures. A 2007 report to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission says that Shipboard Electronic Countermeasures is “a bimonthly periodical sponsored by China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC), 723rd Research Institute in Yangzhou, Jiangsu” which features “academic studies and technical reports on electronic warfare, radar, signal processing, and related technologies.”

SCMP also reported that the paper’s lead researcher was Liu Dongqing, a member of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) Unit 95510. Readily available details about Unit 95510 are limited, but other members of the unit have published research related to electronic warfare work in the past.

The War Zone has also not been able to independently verify any of the other reported details about the January 5, 2021 incident. The claim that “the U.S. military ‘self-destroyed’ its floating sonars” in response to the appearance of Chinese forces seems questionable given that this is very likely to be a reference to sonobuoys. Modern sonobuoy designs, including the ones in use by the U.S. Navy, typically only work for a matter of hours and have deliberate design features to help them sink automatically afterward by default.

The research paper also said more generally that “the U.S. spy planes ‘typically fly at an altitude of 60 metres [sic] (196 feet)’, noting this is a lower cruising altitude than most aircraft and can pose safety risks because it is relatively close to ground level,” according to SCMP. “The scientists said the low altitude is a deliberate tactic used by anti-submarine patrol aircraft, such as the US Navy’s P-8A, to improve the ability to detect and track submarines.”

Low-level tactics, techniques, and procedures employed by anti-submarine warfare aircraft, including the P-8A, are well-documented, as you can read more about in this past War Zone feature. Flying very close to the water allows for more precise sonobuoy emplacement and can help get certain sensors closer to targets of interest. Some sensors, sonobuoys, and anti-submarine weapons simply need to be employed or released closer to the water to function properly.

Flying at lower altitudes does present challenges and increased the vulnerability of anti-submarine warfare aircraft to certain threats. Of course, flying higher exposes them to other risks, including detection and targeting by longer-range radars and surface-to-air missile systems. The U.S. Navy has been pursuing efforts to help expand certain higher-altitude anti-submarine warfare capabilities on the Poseidon specifically.

SCMP‘s initial story framed the incident within the context of a particularly low point in U.S.-China relations compounded by a moment of major domestic political upheaval in the United States. The day after the incident in the South China Sea, a fatal riot over the results of the 2020 presidential election rocked the U.S. Capitol Building. Two days later, in the aftermath of that chaos, U.S. Army Gen. Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, made two unusual calls to his Chinese counterpart. Milley has publicly confirmed those calls and has said he did so after U.S. intelligence showed Chinese officials feared that a conflict was imminent.

U.S.-Chinese relations have remained cool, especially following another surge in tensions last year around a visit by Nancy Pelosi, then a Democratic Party Representative from California and Speaker of House, to Taiwan. The U.S. military has been open about its fears that a conflict with China over Taiwan could emerge before the end of this decade.

However, other portions of the research paper that SCMP highlighted suggest the PLA may view the January 5, 2021 incident, and others like it, as significant outside of any specific temporal context. It also points to broader anti-submarine warfare concerns the PLA has, especially in this highly strategic zone.

“In a time of war, this could pose a detrimental threat to our submarines carrying out critical missions,” Liu Dongqing and his team wrote about the U.S. military capabilities on display during the incident two years ago, according to SCMP. “The purpose is to monitor, block, and contain us.”

The Chinese government has long been sensitive to U.S. military activities in the South China Sea, especially around Hainan and its man-made bases. The U.S. government routinely challenges China’s expansive and largely unrecognized claims that the bulk of the region is its sovereign territory.

Well before January 5, 2021, this had sometimes taken the form of outright harassment of American military aircraft and warships. The most infamous example of this was an incident on April 1, 2001, in which U.S. Navy EP-3E Aries II intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft collided with a PLA J-8 fighter jet, resulting in severe damage to both planes. The J-8 crashed and the pilot was killed in the incident, while the crew of the EP-3E were forced to land on Hainan. The EP-3E’s crew were ultimately repatriated to the United States, but not before they were interrogated and their plane stuffed with extremely sensitive equipment and materials was torn-down and thoroughly examined.

That being said, in recent years, there has been a noticeable uptick in incidents involving U.S. Navy aircraft and ships that would seem to reflect the more general PLA concerns voiced in the recent research paper about American anti-submarine warfare capabilities. Chinese intercepts of Navy P-8As, as well as Poseidons belonging to the Royal Australian Air Force, in the South China Sea in particular, are routine, but there are clear indications that they are getting more assertive and at times even aggressive.

Production crews from CNN and NBC both got something of a direct taste of this during flights aboard Navy P-8As on missions over the South China Sea earlier this year.

Last year, the Australian Department of Defense said that a RAAF P-8As had been damaged after a PLA J-16 Flanker fighter jet released unspecified countermeasures – likely decoy flares – in front of it during an altercation in international airspace over the South China Sea. That followed another incident earlier in 2022 involving a RAAF Poseidon and PLA warships closer to Australia. Interestingly, Chinese authorities claimed that the P-8A dropped sonobuoys around their naval task force during that latter incident.

The PLA’s harassment of other U.S. military assets engaged in the monitoring of Chinese submarine activity, or that at least could have been, extends beyond aircraft, too. In 2009, U.S. officials accused ships from a number of Chinese civil agencies, as well as commercial Chinese fishing boats, of conducting dangerous maneuvers around the ocean surveillance ship USNS Impeccable as it sailed in international waters near Hainan. That ship, as well as the four Victorious class vessels, are the only ones the U.S. Navy currently has that are capable of using the powerful Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS), which is designed to provide “long range detection [of submarines] and cueing for tactical weapons platforms or other vessels of interest.”

The PLA’s brief seizure of a U.S. Navy glider-type uncrewed underwater vehicle (UUV) in 2016 may also have been tied to concerns that the undersea drone was being used to snoop on Chinese submarines.

Chinese aircraft and warships have of course harassed other military assets belonging to the U.S. armed forces and those of other countries in the South China Sea and elsewhere in the Pacific that have nothing to do with anti-submarine warfare. At the same time, the comments in the recent research paper, together with these past incidents, point to the PLA having particularly pronounced fears about the ability of its submarines to operate freely.

The PLAN has worked very hard in the past few decades to significantly expand not only the size of its submarine fleets, but also acquire more advanced types. In parallel, the PLAN has been pushing to conduct submarine operations further and further from the mainland, including with the longer-range deployments of its growing number of Type 094 ballistic missile submarines. This is all in line with broader Chinese efforts to become more of a global military power.

There is similar evidence that the PLA is worried about its own abilities to track and otherwise monitor U.S. and other foreign submarine activity in the Pacific, in general, and that it has been taking steps to expand the scale and scope of its capabilities in this regard.

All of this is also coming amid an increasing willingness on the part of the U.S. Navy to talk about its submarine operations, especially in the Pacific with an eye toward deterring China.

“I would no longer characterize ourselves as a silent service,” Navy Rear Adm. Jeffrey Jablon, the commander of Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (SUBPAC), notably told author and defense expert Robbin Laird earlier this year for a piece Breaking Defense recently published. “Deterrence is a major mission for the submarine force You can’t have a credible deterrent without communicating your capabilities; if the adversary doesn’t know anything about that specific deterrent, it’s not a deterrent.”

Altogether, no matter what exactly transpired in the northern portion of the South China Sea on January 5, 2021, the PLA-linked research paper, at least reported by SCMP, makes clear that Chinese authorities took notice. That now-disclosed incident speaks to broader Chinese concerns about American anti-submarine warfare capabilities in the region and increasing undersea competition between the two countries. And yet it is just one small snapshot of a much wider picture, one in which similar incidents likely happen with increasing regularity without ever being reported.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com