The U.S. Navy is in process of developing a new, more rapidly deployable, fixed, persistent, deep water active anti-submarine surveillance system. This system would consist of large sonar arrays attached to buoys that ships could emplace in a particular spot in the ocean straight from inside a standard shipping container. This is just one part of a multi-tier effort that comes as senior naval officers continue to warn publicly about increasing worrisome submarine activity from potential adversaries, especially with regards to Russian subs operating more regularly off the coast of the Eastern United States.

On Feb. 19, 2020, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) issued a notice on beta.SAM.gov, the U.S. government’s central contracting website, asking for white papers detailing possible options to meet the demands for what it is calling the Affordable Mobile Anti-Submarine Warfare Surveillance System, or AMASS. ONR’s goal is to eventually develop a “persistent, deep water, active ASW [anti-submarine warfare] system that can detect new emerging threat submarines at extended ranges.”

The AMASS effort is still in the very early stages and ONR has offered only a limited number of desired capabilities so far. The notice on beta.SAM.gov says that the Navy wants the buoy to deploy the active sonar array automatically and be able to keep the entire system fixed in place in a particular area for a protracted period of time.

The array also has to be sufficiently rugged to resist “deformation so as not to compromise sonar performance” as it sits in the underwater currents. As its name implies, “total cost of system should be affordable,” ONR notes.

Most interestingly, ONR is asking for proposals that involve buoys and attached sonar arrays that can fit inside a standard shipping container and that crews onboard could deploy straight from there into the water. This would certainly help reduce costs by enabling a wide array of ships to carry the AMASS sonar arrays and emplace them wherever necessary. This might include cargo ships or other auxiliaries assigned to the Navy’s Military Sealift Command or contractor-operated vessels.

The Navy says that AMASS is intended as a supplement, not a replacement for “established Fixed Surveillance Systems (FSS) and Mobile Surveillance Systems (MSS).” The FSS refers to fixed deepwater passive sensor networks, the best known of which is the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS). SOSUS, the first versions of which entered service in 1959, had already seen its military function diminished by the end of the Cold War and had become used increasingly for scientific research, a role that it continues to perform to this day.

The Navy is tight-lipped about the exact scope and scale the latest iteration of its fixed anti-submarine surveillance system, but the service has expanded and improved its capabilities over the years to keep up with advances in submarine design and other technology. In addition, there have been upgrades to reduce the need for vulnerable physical undersea cables to send and receive information from the sensor nodes.

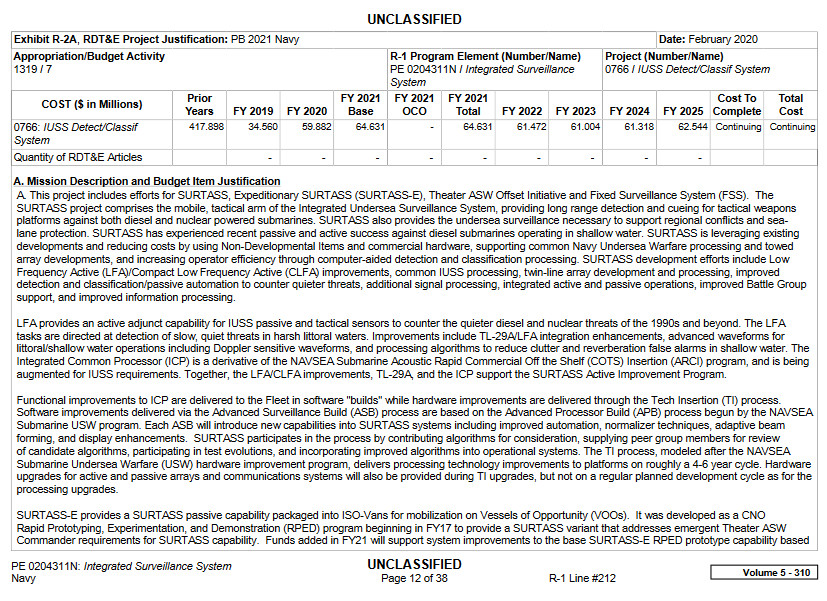

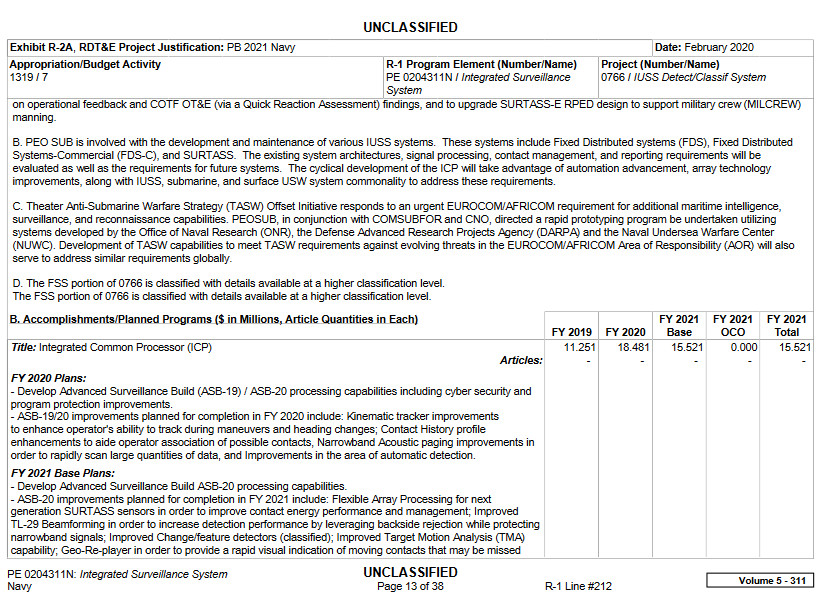

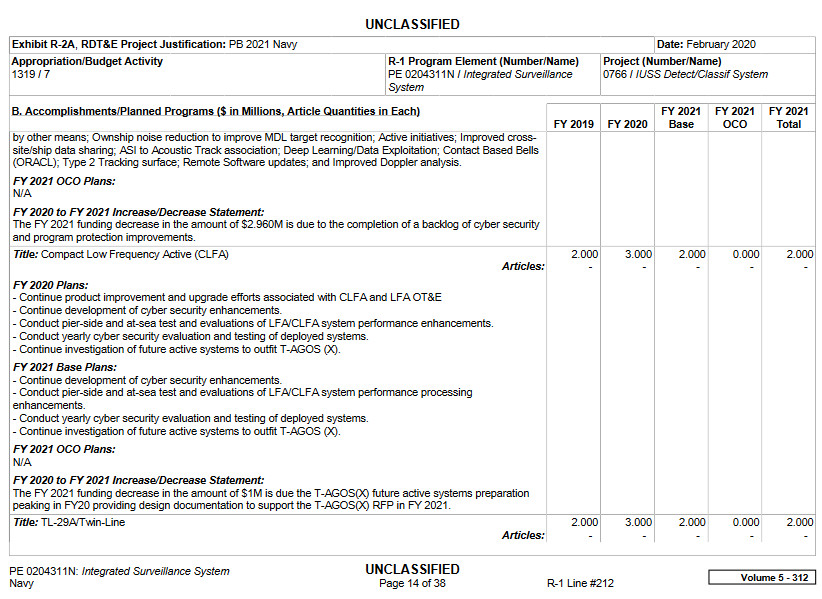

The MSS component refers to ship-towed passive and active sonar arrays, also known as the Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS). “SURTASS provides … long range detection [of submarines] and cueing for tactical weapons platforms or other vessels of interest,” according to the Navy.

The system’s Low Frequency Active (LFA) sonar capability, which the Navy added in the late 1980s, “provides an active adjunct capability for IUSS passive and tactical sensors to assist in countering the quieter diesel and nuclear threats of the 1990s and beyond,” according to the service. “The LFA tasks are directed at detection of slow quiet threats in harsh littoral waters.”

The Navy originally fielded SURTASS on its Stalwart class ocean surveillance ships, but then switched to catamaran-style vessels with the introduction of the LFA upgrade. After the end of the Cold War, the service substantially scaled back its plans for the SURTASS system.

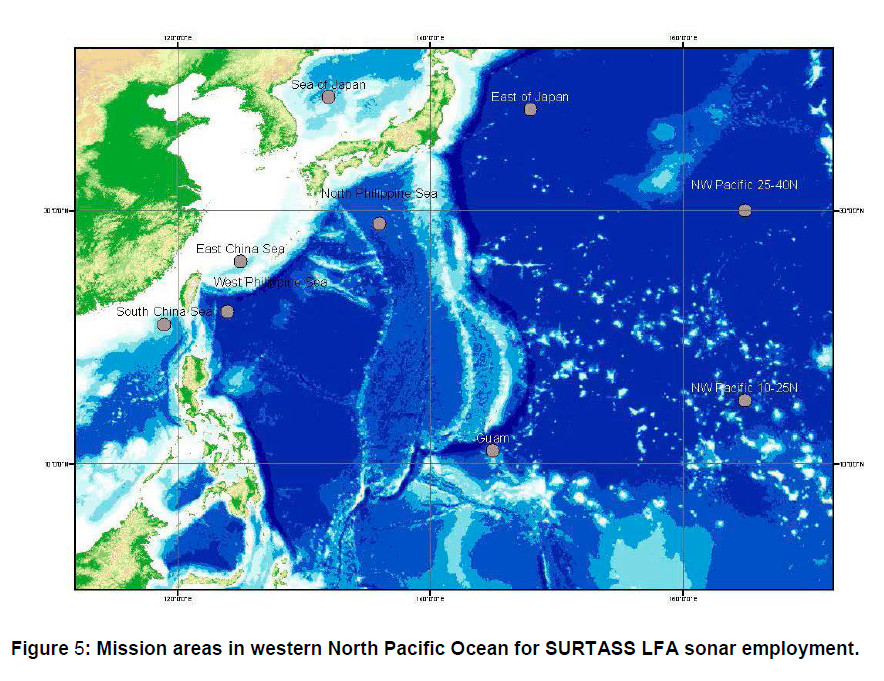

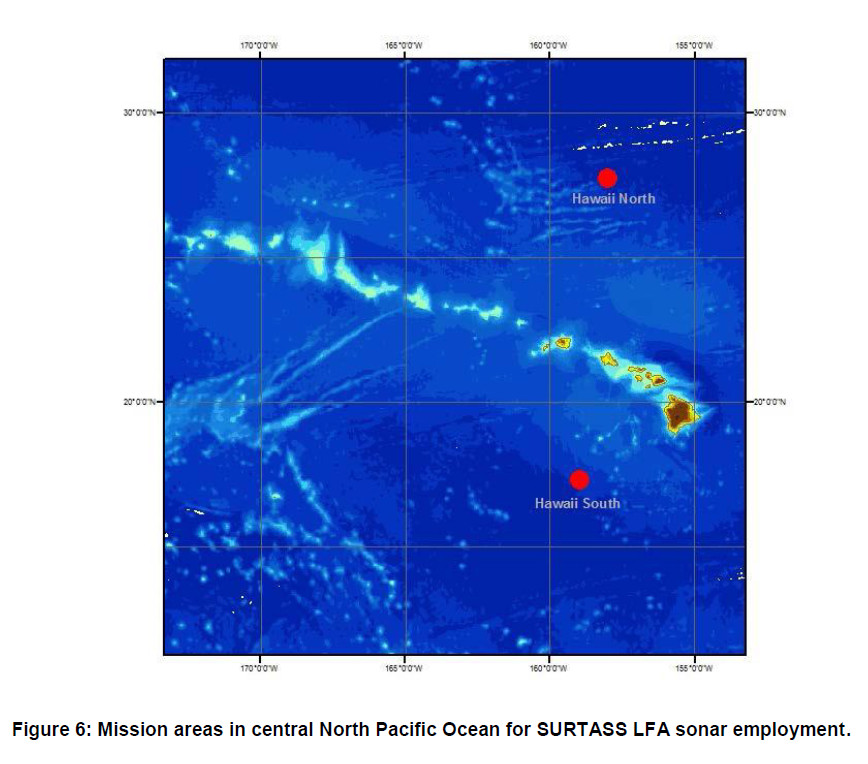

At present, the only ships equipped to employ the latest iteration of the SURTASS towed array, also known as the TB-29A Twin-Line Array, are the USNS Impeccable and the four ships in the Victorious class. Japan also operates three Hibiki class ocean surveillance ships, which are also catamaran types, equipped with SURTASS.

The FSS and MSS together, along with associated communications networks and other infrastructure, form the Navy’s Integrated Underwater Surveillance System (IUSS). AMASS is also only one part of a larger plan for a new family of Deployable Surveillance Systems (DSS). AMASS would fill the role of the DSS-Deep Water Active (DSS-DWA) component.

Active sonar systems, such as the kinds ONR is seeking for AMASS program, detect threats by sending out pulsed soundwaves and then listening for the echoes as they bounce off objects in the distance. Passive sonars, as well as other passive sensor systems, such as hydrophones, simply allow operators to listen for telltale sounds belonging to submarines below the water or ships sailing above. Some sonar systems have both active and passive modes.

The video below from retired Navy submariner Aaron ‘Jive Turkey’ Amick offers a more detailed description of the differences between active and passive sonar:

The issue with active sonars is that, by emitting the sound pulses, they alert opponents to their presence, giving them the opportunity to attempt to evade or avoid detection. It also makes them easy to detect and therefore vulnerable to hostile action. It’s not clear how a persistent active sonar system might work in practice, but it could only activate when passive sensors detect an object of interest.

The Navy’s plans for the complete DSS family does also include a DSS Deep Water Passive (DSS-DWP) component, as well as a system that is “mobile” and can operate in both active and passive modes. It’s not entirely clear if the mobile component, also known DSS-MPAS, would be an array that ship would tow, as is the case now with SURTASS, or if it would be some sort of unmanned system capable of redeploying by itself.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) had worked on distributed anti-submarine hunting system in the past, known as the Distributed Agile Submarine Hunting (DASH), which would employ unmanned underwater vehicles (UUV), dubbed Submarine Hold at RisK (SHARK), to persistently track hostile submarines after other sensors first detected them. DASH also included the development of the Transformational Reliable Acoustic Path System (TRAPS), which are fixed passive sonar nodes that sit on the seafloor. DARPA had also envisioned locating and tracking enemy submarines as a key role for the Sea Hunter unmanned surface vessel, which is now a Navy program.

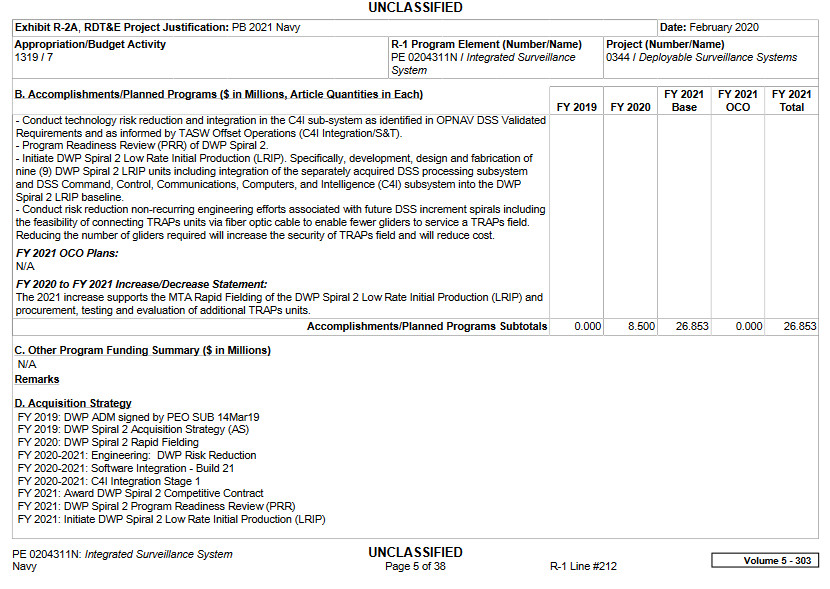

The Navy has also taken responsibility for TRAPS, has fielded it, and is now looking to integrate it into its plans for the DSS. It’s also interesting to note that the service says in its most recent budget proposal for the 2021 FIscal Year that it is employing unmanned glider-type UUVs to service TRAPS sensor “fields.” This might help further explain why the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy briefly seized one of these underwater drones in the South China Sea in December 2016.

“Conduct risk reduction non-recurring engineering efforts associated with future DSS increment spirals including the feasibility of connecting TRAPs units via fiber optic cable to enable fewer gliders to service a TRAPs field,” the budget request says. “Reducing the number of gliders required will increase the security of TRAPs field and will reduce cost.”

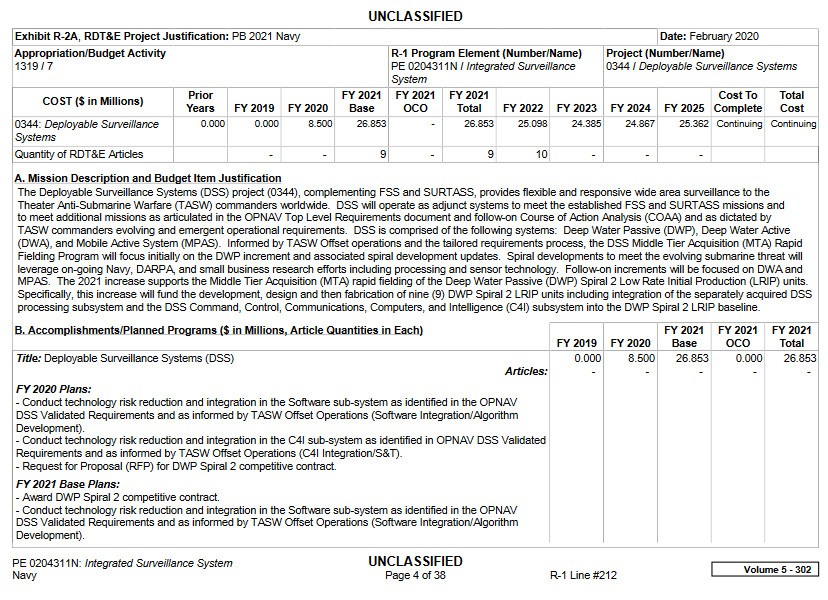

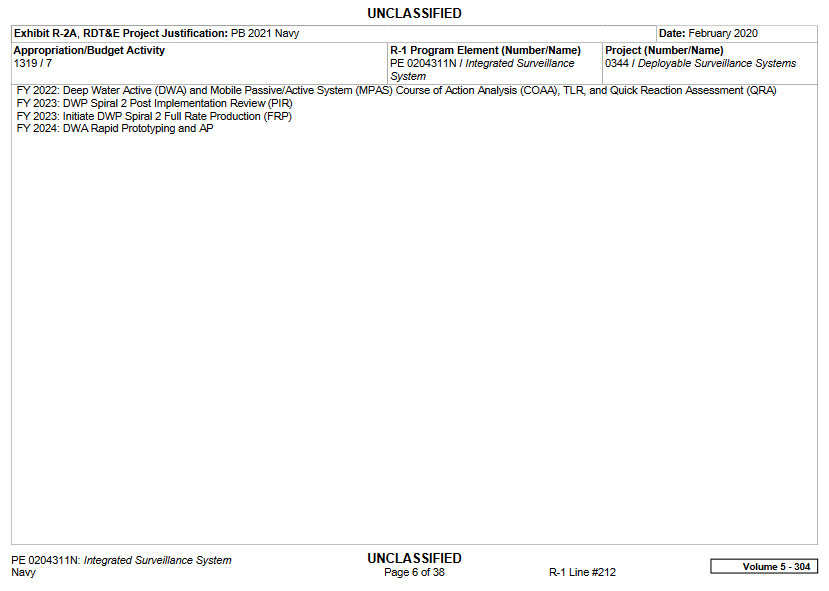

The Navy is asking for nearly $27 million for this and other work on the DSS program in the 2021 Fiscal Year. The service hopes to get the first limited-run production examples of the DSS-DWP system this year under a rapid fielding initiative. A decision on how to proceed with the DSS-DWA and DSS-MPAS components is scheduled to occur in the 2022 Fiscal Year.

The primary goal of the entire DSS effort is “to provide flexible and responsive wide area surveillance to Theatre Anti-Submarine Warfare (TASW) Commanders worldwide” that is “designed to address operational gaps,” according to ONR. This makes sense given how vocal senior Navy officers have been about increasing submarine threats, especially from Russia and China. Both countries are working to expand their submarine fleets and are developing more advanced nuclear-powered and diesel-electric designs that are quieter and therefore harder to detect. You can read more about these growing concerns in-depth in these past War Zone stories.

When it comes to monitoring this increasing submarine activity, the obvious immediate issue for the existing IUSS is that the fixed component is just that, fixed. At the same time, with only five SURTASS ships available, the mobile component can only monitor so many locations at once.

The limited size of the SURTASS fleet, combined with restrictions on the use of the LFA sonar array, due to concerns about its impact on marine life, also makes the movement of those ships more predictable. This, in turn, makes those ships vulnerable to harassment, or potentially worse during an actual conflict. China’s quasi-military maritime militia, also known as the “Little Blue Men,” which routinely squares off with foreign ships in areas of the South China Sea that Beijing sees as its exclusive territory, notably made dangerous maneuvers around USNS Impeccable while she sailed in international waters near Hainan Island in 2009. China’s largest submarine base is located on the island’s southern tip.

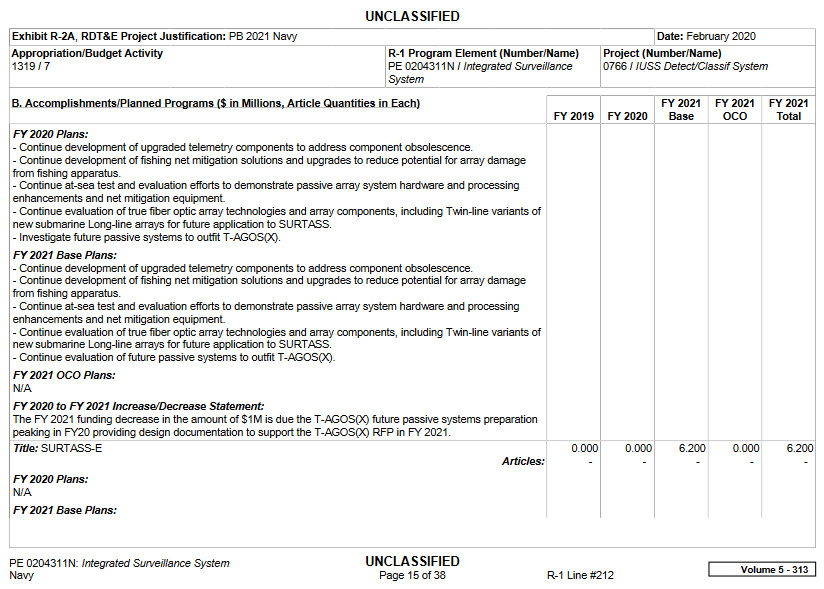

In 2017, the Navy began work on a program known as the Expeditionary Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System, or SURTASS-E, which “provides a SURTASS passive capability packaged into ISO-Vans [standardized shipping containers] for mobilization on Vessels of Opportunity (VOOs),” according to official budget documents, which also cover various other work on sustaining and modernizing the IUSS, as a whole. As such, SURTASS-E offers greater flexibility in that it could be installed readily on various ships, but also does not feature the active sonar capability found on ships equipped with the standard SURTASS system.

In 2018, the Navy chartered an unknown vessel as part of the SURTASS-E Rapid Prototyping, Experimentation, and Demonstration (RPED) effort. That ship took this modular towed sonar system on its first-ever operational patrol in the Atlantic last year.

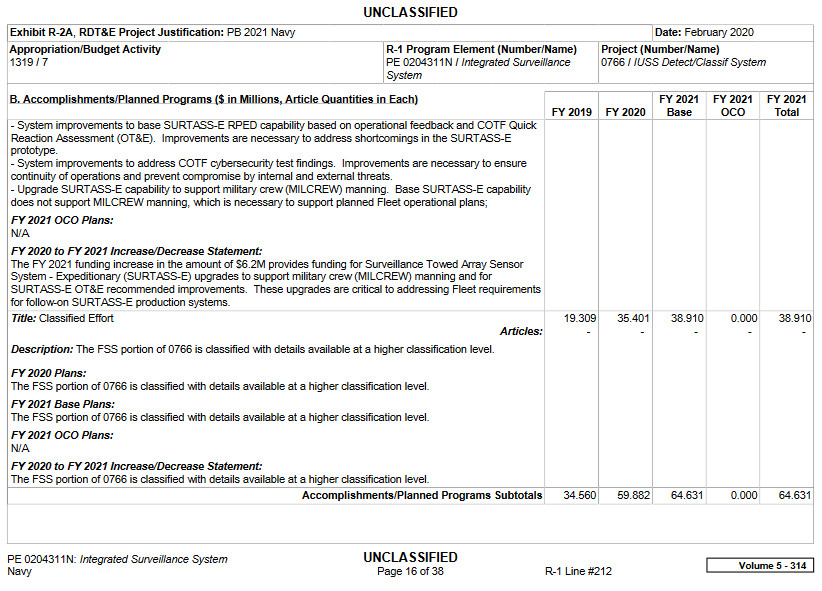

The service is now asking for $6.2 million in its most recent budget request for the 2021 Fiscal Year to “support system improvements to the base SURTASS-E RPED prototype capability based on operational feedback and COTF OT&E [operational test and evaluation] (via a Quick Reaction Assessment) findings, and to upgrade SURTASS-E RPED design to support military crew (MILCREW) manning.”

In addition, SURTASS-E, while more flexible than SURTASS, still requires available ships, something the Navy is struggling to provide for basic operational requirements at present, and it still cannot remain in a particular place indefinitely. The complete DSS system, including AMASS, would offer a valuable added layer of capability that the service could deploy and then leave in place on-demand. DSS would also have the benefit of being less predictable, but far more capable and persistent than something like an array of air-deployed sonobuoys.

All told, it’s clear that the Navy sees its existing fixed sensor arrays, as well as its available ship-towed wide-area sonar surveillance assets, as too limited in both capability and capacity to meet the demands of an increasingly challenging underwater military ecosystem that is emerging around the world. While the service doesn’t immediately plan to replace any of those maritime surveillance systems, its plans for the new Deployable Surveillance System show that it is working to take its anti-submarine monitoring capabilities in an exciting new and more flexible direction.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com