A senior U.S. government official has indicated that Russia already has some kind of clandestine testbed in space as part of its development of a nuclear-armed on-orbit anti-satellite weapon. This comes just days after another official warned Congress that this “indiscriminate” weapon, details about which first emerged publicly earlier this year, could be capable of rendering low Earth orbit completely unusable for a prolonged period of time.

Mallory Stewart, Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability, discussed Russia’s nuclear anti-satellite weapon developments in new detail today in a fireside chat that the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank in Washington, D.C., hosted.

“The United States is extremely concerned that Russia may be considering the incorporation of nuclear weapons into its counterspace programs based on information we deem credible,” Stewart said. “The United States has been aware of Russia’s pursuit of this sort of capability dating back years, but only recently have we been able to make a more precise assessment of their progress.”

Stewart stressed at multiple times during the conversation that the U.S. government has not assessed that Russia has “deployed” this capability in any way, and that American officials are actively trying to discourage that from happening.

However, the Assistant Secretary of State did indicate that something is in space now as part of the development of this new nuclear anti-satellite weapon.

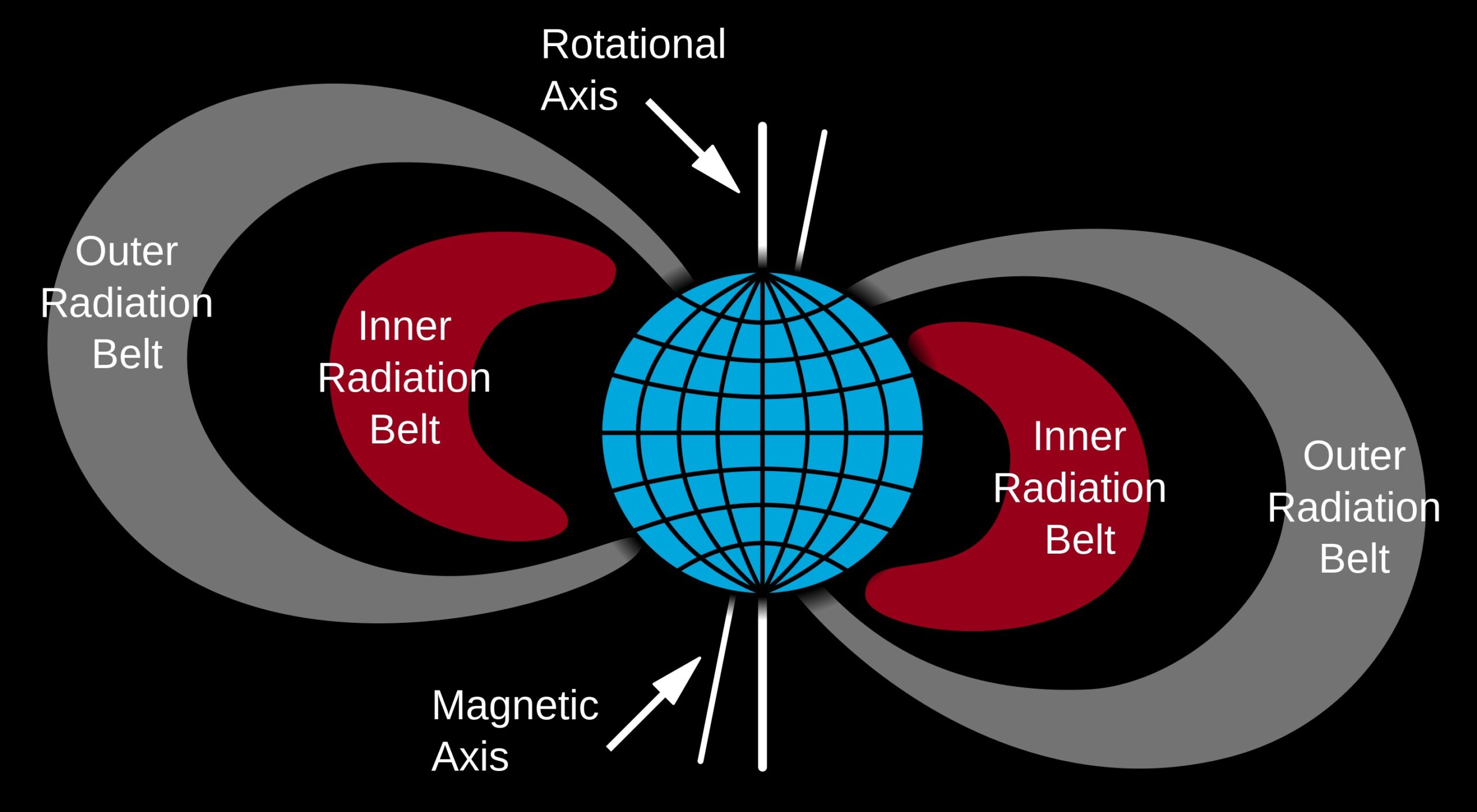

“Russia has publicly claimed that their satellite is for scientific purposes,” Stewart said “However, the orbit is in a region not used by any other spacecraft. That in itself was somewhat unusual. And the orbit is a region of higher radiation than normal, lower earth orbits, but not high enough of a radiation environment to allow accelerated testing of electronics as Russia has described the purpose to be.”

Stewart did not name the satellite in question or elaborate on its claimed purpose. Putting some kind of testbed in orbit before deploying an actual space-based weapon system, especially one involving a nuclear weapon system, would make good sense. This would be even more prudent if the orbit passes through areas where there is increased radiation risks, the Van Allen belts, something we will come back to later.

The Assistant Secretary of State did provide some additional context about the anti-satellite capability that Russia is using that platform, at least in part, to help develop.

“We aren’t talking about a weapon that can be used to attack humans or cause structural damage on Earth,” according to Stewart. “Instead… our analysts assess that detonation [of a nuclear device] in a particular placement in orbit of a magnitude and location would render lower Earth orbit unusable for a certain amount of time.” Low Earth Orbit (LEO) refers to a band of space that measures roughly 100 miles to 1,200 miles above the earth, and which is highly congested. Many capabilities that are highly important to society exist in this orbital realm.

In talking about the projected anti-satellite weapon’s capabilities, Stewart also referenced remarks from Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy John Plumb earlier this week. Plumb discussed this same topic at a hearing before members of the House Armed Services Committee on May 1. There, he answered questions on a written statement to Congress regarding the Department of Defense’s 2025 Fiscal Year budget request.

“The concept that we are concerned about is Russia developing and — if we are unable to convince them otherwise — to ultimately fly a nuclear weapon in space,” Plumb said earlier in the week. This concerns an “indiscriminate weapon [that] doesn’t have national boundaries, [and] doesn’t determine between military satellites, civilian satellites or commercial satellites,” Plumb said.

When pressed by Representative Mike Turner (R-Ohio), who chairs the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, on the impact that detonating such a weapon in space could have, Plumb indicated that coming to a definitive conclusion remains challenging. However, he did note that “satellites that aren’t hardened against nuclear detonation space, which is most satellites, could be damaged [and] affected… Some would be caught in an immediate blast which… would not be able to survive the flux of that, and then others could be damaged over time.”

Here, Plumb referred to the impact of ‘nuclear pumping’ in the aforementioned Van Allen Belts — high energy radiation particles that form two belts that surround the Earth like donuts. Nuclear pumping refers to a phenomenon where nuclear radiation lingers in the LEO environment.

The effects of this were demonstrated during the U.S. Starfish Prime nuclear test in 1962, which “pumped” the LEO region with radiation, taking down numerous satellites.

Concerningly, Plumb indicated that LEO could feasibly be rendered unusable for a year if Russia’s new weapon was detonated in space. As he noted in his written testimony, Plumb stipulated that this would seriously threaten “all satellites operated by countries and companies around the globe, as well as to the vital communications, scientific, meteorological, agricultural, commercial, and national security services we all depend upon.”

On the developmental status of Russia’s nuclear-armed anti-satellite weapon, Plumb said that specific details could only be discussed in closed session. He did note that the threat isn’t “imminent in the way that we should have to worry about it right now.” “But,” he added, “we are concerned about it… [both] the Department [of Defense] and the entire [Biden] administration, and I know this Congress is taking this deadly seriously.”

While further details on the progress on the weapon, beyond Mallory and Plumb’s recent comments, aren’t available outside of the classified realm, there have been recent indications that Russia is actively pursuing such a capability. In late April, Russia vetoed a United Nations (U.N.) Security Council resolution, proposed by the U.S. and Japan. Said resolution directed members to uphold Article 4 of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which Russia signed 56 years ago, forbidding countries from placing nuclear weapons in orbit or on celestial bodies. The treaty also prohibits countries from developing nuclear weapons, or other weapons of mass destruction, for use in orbit.

The White House condemned Russia’s decision to veto the resolution at the time, constituting the first public confirmation by the U.S. government that Russia’s new anti-satellite weapon is nuclear-armed. Previously, this had only been attributed to anonymous official sources.

In a statement released on April 24, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that “the United States assesses that Russia is developing a new satellite carrying a nuclear device. We have heard President Putin say publicly that Russia has no intention of deploying nuclear weapons in space. If that were the case, Russia would not have vetoed this resolution.”

Russia has since circulated its own U.N. resolution on the matter of space-based nuclear weapons that not only calls for preventing such weapons from being deployed in space, but also stopping “the threat or use of force in outer space” for “all time.”

The matter of Russia’s vetoing of the resolution will be deliberated on in the U.N. General Assembly on May 6, Stewart said today, which will be open to all U.N. member nations. The U.S. has also been leveraging its diplomatic resources to bolster international opposition to Russia’s decision, she confirmed, having already consulted with U.N. members China and India.

“I think the international response [to the existence of the weapon] should be outreach,” Stewart said, “because it affects everyone right, every single country is indiscriminate in its potential effect. So it’s much different than efforts to hold us at risk limited to just the U.S. and our partners [and] allies. It would affect everyone including China and India, and Russia’s own satellites. So it’s extraordinarily destabilizing, and I think the international community needs to reflect that concern.”

That being said, the existence of Russia’s nuclear anti-satellite weapon is concerning to the U.S. government and military for a host of reasons. Space represents an absolutely critical domain and is essential for the day-to-day functioning of the U.S. military. Moreover, it has in place various programs for developing distributed space-based capabilities, supporting early warning and missile-defense type missions, as well as intelligence-gathering and surveillance, communications and data-sharing, where satellite use is key. The United States’ advantage in space is clearly something adversaries are seeking to negate, potentially at great cost.

Already, adversaries such as Russia and China have developed various anti-satellite weapons, including direct ascent interceptors, ‘killer satellites,’ electronic warfare jammers, and lasers. The collective threat posed by these adversarial capabilities has been previously described as “extremely concerning” by the U.S. Space Force’s top officer Gen. Chance Saltzman. In response, the U.S. armed forces have explored the use of different commercial options, including systems like SpaceX’s Starlink, for conducting future operations via distributed satellite constellations.

And while U.S. adversaries look for new ways to target massive constellations of smaller satellites in LEO, it’s possible that deploying nuclear weapons in that region — as dangerous a prospect as this would be for all space users — may look increasingly attractive to other countries aside from just Russia.

Beyond the military aspect, once again, the loss of low earth orbit would be hugely impactful to life on Earth. The economic damage that such a weapon could do is hard to even quantify. Replacing space-based capabilities after the radiation cleared would take a very long time and LEO may be so cluttered with space junk at that point that it may not be reliably inhabitable at all for much longer than how long damaging radiation would persist.

The entire idea of this weapon is very troublesome and the use of it could set humanity back significantly for a long time.

If anything else, these new revelations about Russia’s nuclear anti-satellite weapon underscore just how real a battlefield space is becoming.

Contact the authors: oliver@thewarzone.com, joe@twz.com