Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki says his country wants to join NATO’s nuclear weapon sharing program. This is in direct response to Russia’s deployment of some of its own nuclear weapons to neighboring Belarus. This also comes as Poland is pushing ahead with a massive conventional rearmament effort that was accelerated in the wake of the all-out Russian invasion of Ukraine last year.

Prime Minister Morawiecki made his remarks about Poland’s desire to become of NATO’s nuclear weapon sharing arrangements in response to a question at a press conference on the sidelines of a European Union in Brussels, Belgium, earlier today.

“The final decision will depend on our American and NATO partners. We declare our will to act quickly in this matter,” Morawiecki said, according to Polesat News. “We do not want to sit idly by while [Russian President Vladimir] Putin escalates all sorts of threats.”

Putin said earlier this month that Russian nuclear weapons had begun to arrive in Belarus as part of an agreement the two countries cut last summer. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko said earlier this week that a ” significant” portion of the total number of nuclear munitions that Russia plans to place in his nation have now arrived. Per previous statements from Putin and Lukashenko, these weapons are a mixture of nuclear-capable Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles and air-dropped nuclear bombs, the latter of which the Belarusian Air Force now claims to be capable of employing.

This is not the first time Polish authorities have publicly stated their interest in joining the NATO nuclear weapon sharing program in light of Russia’s decision to deploy nuclear weapons in Belarus.

“There is always a potential opportunity to participate in the nuclear sharing program,” Polish President Andrzej Duda said in October. “We have spoken with American leaders about whether the United States is considering such a possibility. The issue is open.”

That same month, NATO conducted the annual iteration of its nuclear deterrence exercise, Steadfast Noon, which includes practicing putting the alliance’s nuclear weapon sharing plans into action. The Polish military took part in that exercise, but in a supporting role rather than as one of the members that would be actually employing nuclear munitions.

“We would like to stress that Poland did not strive for the possession of nuclear weapons,” a spokesperson for the Polish Ministry of Defense told The War Zone at the time. “As a NATO member, we participate in the Alliance’s nuclear policy and are also covered by the guarantees of the Allied Nuclear Sharing program.”

At present, NATO’s nuclear weapon sharing agreement is entirely centered on U.S. B61-series air-dropped nuclear bombs. The program provides for the forward deployment of these weapons in secure vaults at air bases in multiple member nations under U.S. military control. In a crisis where the alliance approves their use, they would then be loaded onto combat jets belonging to participating countries. NATO aircraft capable of employing these nuclear weapons are known as Dual Capable Aircraft (DCA), referring to the dual nuclear and conventional capabilities.

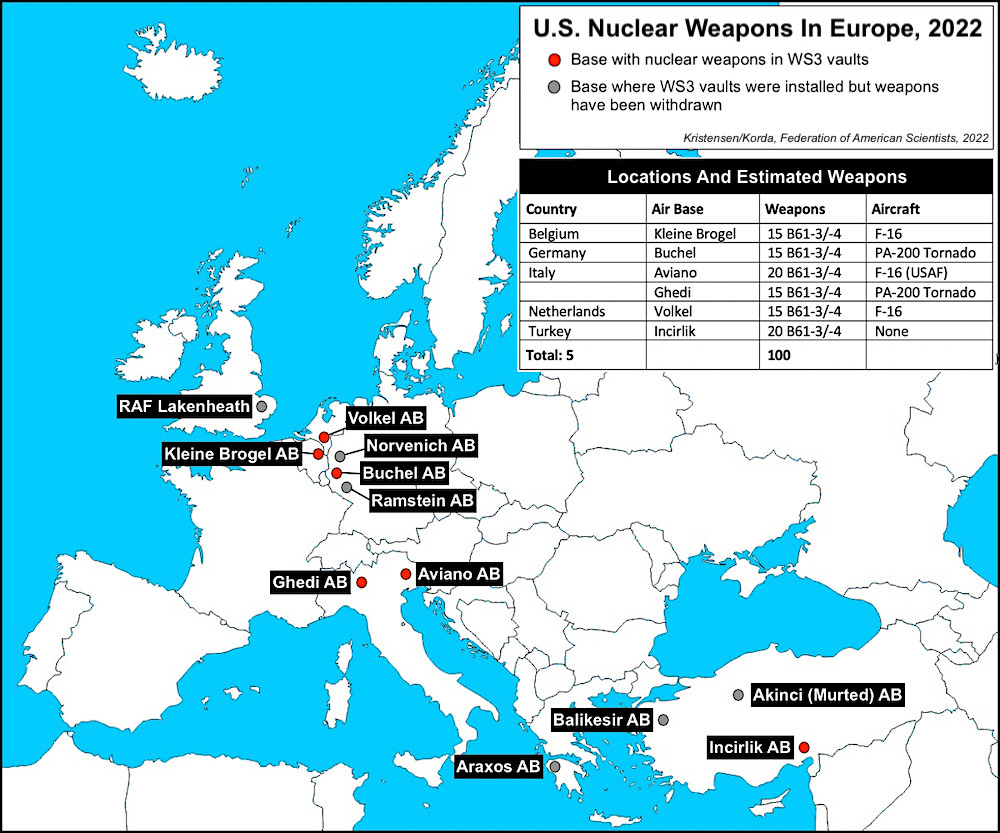

Specific details about the program are both classified and politically sensitive for many of the participating countries, a number of which do not even publicly acknowledge the presence of American nuclear weapons on their soil. As of last October, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) estimated that around 100 B61s in total were spread across six bases in five countries – Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. There have been estimates as high as between 150 and 200 bombs in the past.

At that time, NATO had publicly acknowledged seven members of the nuclear sharing program, did not name them. This list is at least understood to include Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Turkey continues to host weapons, but it has long been reported that it is no longer active itself in the nuclear sharing arrangements and no longer operates DCA aircraft. The chill in U.S.-Turkish relations following the attempted coup against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2016 also prompted speculation that the B61s could be withdrawn from the country, but there is no evidence that has happened to date. NATO outright denied a report in 2016 that those bombs had been relocated to Romania.

FAS suggested last year, given the total number of NATO nuclear weapon sharing program participants, that Turkey could still have a reserve role of some kind. It reported at that time that Greece, which no longer hosts bombs or has DCA aircraft, was also among the seven countries, but again in a reserve capacity.

The United Kingdom has also hosted U.S. nuclear weapons under the NATO nuclear sharing agreement in the past, but those bombs were withdrawn by 2007 at the latest, according to FAS. The U.S. military’s 2023 Fiscal Year budget proposal included a mention of work to modernize nuclear weapon storage facilities in the United Kingdom, suggesting that there could be plans in the works to redeploy B61 bombs there in the future.

In response to a Freedom of Information request The War Zone submitted last year asking for details about “the current… participation of the United Kingdom in NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements, whether or not the country operates dual-capable aircraft (DCA), and/or whether the country hosts U.S. nuclear gravity bombs of any type,” the U.K. Ministry of Defense said it “neither confirms nor denies” any relevant information.

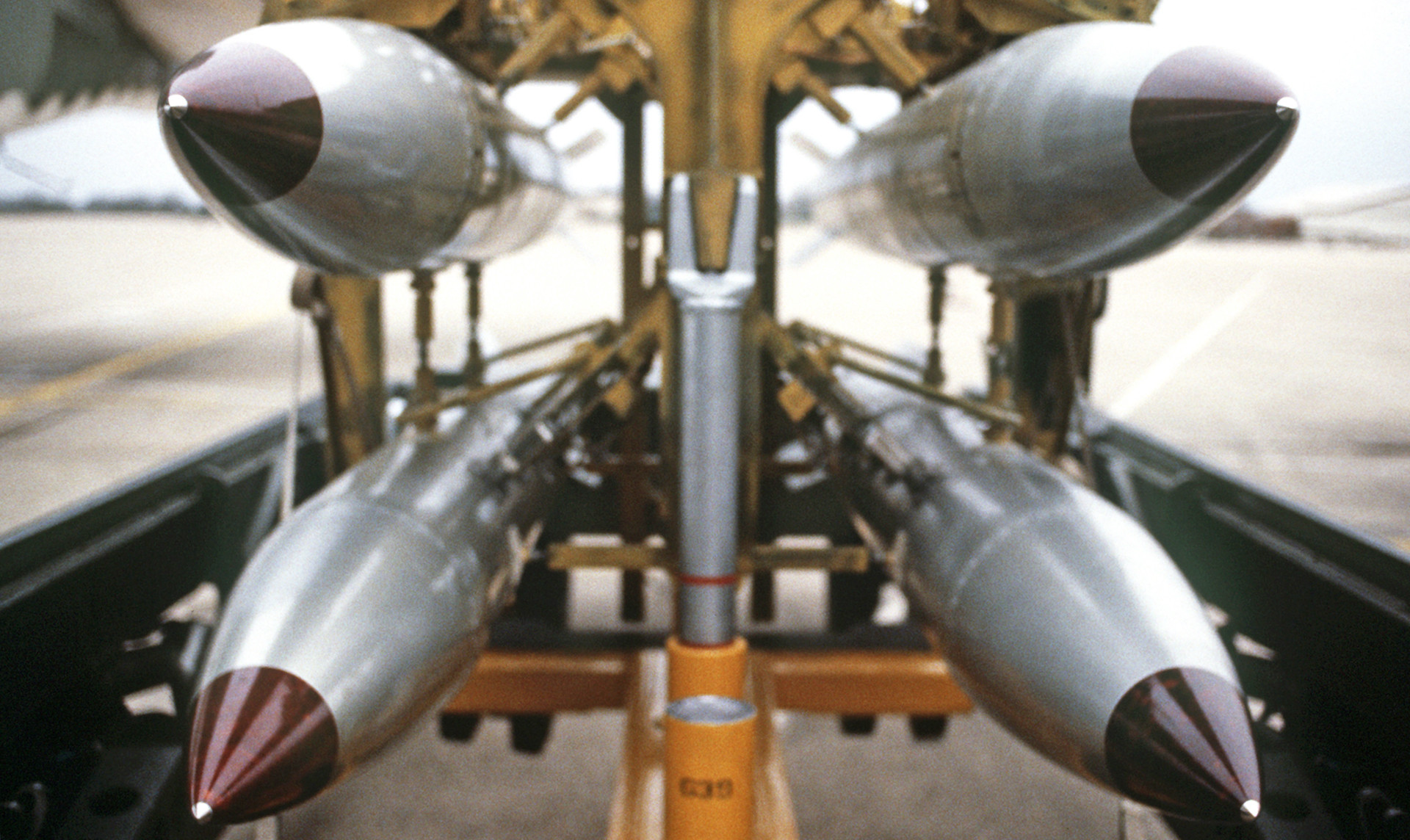

As for the actual bombs that make up the core of the NATO nuclear weapon sharing program, these are currently understood to be B61-3 and/or -4 variants, which American authorities categorize as tactical nuclear weapons. Both are so-called “dial-a-yield” designs where the total explosive force of the weapon can be set before employment. The B61-3 reportedly has eight separate yield settings: 0.3, 1.5, 5, 10, 45, 60, 80, or 170 kilotons. The B61-4 is understood to have fewer that only range from 0.3 to 50 kilotons. You can read more about the entire B61 family here.

The U.S. military is in the process of replacing the bulk of its B61-series bombs with new B61-12 versions, which include remanufactured components for B61-3s, -4s, -7s, and -10s. They also incorporate new features, most notably a precision guidance tail kit, as you can learn more about here.

U.S. Air Force F-15E Strike Eagle combat jets, B-2 Spirit bombers, and some F-16 Viper fighters are certified to employ existing B61 variants. As part of the nuclear weapon sharing agreement, some Belgian, Dutch, and Italian F-16s, as well as German Panavia Tornado swing-wing combat jets, are also capable of dropping these weapons. In order to be able to drop these bombs, the launching aircraft needs to have special modifications to be able to “talk” with the weapons in order to transmit the necessary secure codes to activate them and set the yields via what are known as Permissive Action Links (PAL).

The U.S. military has been working to integrate the B61-12 onto the F-15E, F-16, and B-2, as well as the F-35A Joint Strike Fighter, in support of its own requirements and those of NATO. The U.S. Air Force’s future B-21 Raider stealth bombers will also be capable of dropping these bombs. Interestingly, at present, the only platforms expected to be able to make use of the new guided functionality of the B61-12 will be the F-15E, F-35A, B-2, and B-21. F-16s will only be able to employ them in their unguided mode.

Reports emerged last year that the U.S. military was looking to accelerate the fielding of the B61-12 in Europe in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it’s unclear whether or not this has actually started. It is known that fit checks have been conducted to ensure that the new B61 version can fit inside existing secure vaults.

Altogether, at least from a technical standpoint, if Poland is to join the NATO nuclear weapon sharing program, it will need to modify a certain number of its combat jets. The country already operates F-16s that could be configured for this role and is in the process of acquiring F-35As. If it were to physically host bombs inside its borders, it would also need to build the requisite secure facilities. Other relevant security and safety policies and protocols would also need to be implemented.

It is possible that Poland could join the program on a more truncated timetable by first modifying aircraft and planning to have them operate from NATO bases where B61s are already stored. The country could also serve as a forward staging point for nuclear-armed DCA aircraft.

It of course remains to be seen whether or not Poland will actually join NATO’s nuclear weapon sharing program. At the same time, it would align in many ways with the country’s existing conventional rearmament, which has further ballooned in the wake of Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine.

Just this week, Poland received its first M1 Abrams main battle tanks from the United States and the country is also in the process of acquiring K2 tanks from South Korea. That latter purchase is just one element of a massive arms deal the Polish and South Korean governments concluded last year that also includes combat jets and self-propelled artillery, along with industrial cooperation agreements.

M1s are hardly the only new weapons the Polish are buying from the United States. Poland is on track to become the second-largest operator of AH-64 Apache attack helicopters in the world and U.S. authorities just recently authorized a potential $15 billion-dollar sale of Patriot surface-to-air missile systems, Integrated Battle Command Systems IBCS), and other related material and services. On the air and missile defense side of things, Poland is on track to become the first U.S. ally to field IBCS, a powerful network architecture that can link various weapons and systems together that you can read more about in this past War Zone feature.

In January, the Polish government announced its intention to increase the size of its defense budget to four percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), a decision authorities there said was being driven by the conflict in Ukraine. This would make it the highest per-capita spender in NATO, even above the United States. The alliance requires its members to strive for a goal of at least two percent GDP spending on defense, but few members actually meet this target.

Poland has of course seen the potential for spillover from the conflict in Ukraine firsthand, when what was likely a stray Ukrainian surface-to-air missile killed two Polish farmers in November 2022. At the same time, Warsaw has been raising concerns about Russian aggression for years now and its military buildup predates the current fighting in Ukraine or the deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus.

The Polish government has had its own concerns about security threats emanating from Belarus, as well. In 2021, a crisis emerged along Belarus’ borders with Poland, as well as Latvia, and Lithuania, with migrants from the Middle East finding themselves trapped in between. Polish and other European authorities accused the Belruarisan government of weaponizing those individuals to deliberately foment unrest.

Poland stepped up security along its border with Belarus again after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is now further reinforcing those defenses in light of reports that thousands of members of the Russian private military Wagner are relocating to Belarus following an abortive putsch on Moscow led by the group’s leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin.

All told, whether or not Poland ends up hosting nuclear weapons itself, the country is already becoming a major driving force in NATO and European defense and security discussions.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com