Members of the U.S. Senate are looking to not only block the U.S. Navy from sending dozens of EA-18G Growler electronic attack aircraft into storage, but are also proposing that the service join together with the U.S. Air Force to form a new land-based aerial electronic warfare force. In its 2023 Fiscal Year budget request, the Navy had proposed shutting down all five of its non-carrier-based active component expeditionary electronic attack squadrons and sending the 25 jets currently assigned to those units to the boneyard in Tucson, Arizona for long-term storage.

The Senate Armed Services Committee advanced a version of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the 2023 Fiscal year containing the EA-18G-related provisions, among other things, on June 16, 2022. This draft legislation first needs to be brought in line with a similar bill now being put together in the House of Representatives, and then passed by both chambers, before it could be signed into law, a process that often takes months.

The Senate’s bill, as it stands now, “requires retention of the EA-18G aircraft” and the “transfer of EA-18Gs in expeditionary electronic attack squadrons to the Navy Reserve Air Forces,” according to a summary released yesterday.

In addition, it would demand the “designation of one or more units from the Air National Guard or Air Force Reserve to join with the Navy Reserve to establish joint service expeditionary, land-based electronic attack” force and “a report on the plan of the Secretaries of the Navy and Air Force to implement this plan.”

Most immediately, this legislation would put a halt to the Navy’s previously stated desire to put the 25 EA-18Gs currently spread across five active component land-based expeditionary electronic attack squadrons in storage and cut the 1,020 officers and enlisted personnel assigned to those units. In documents released earlier this year as part of its proposed 2023 Fiscal Year budget, the service had said this would free up nearly $808 million in funds that could be redirected to other priorities.

It is hardly uncommon for members of Congress to push for and succeed in blocking various branches of the U.S. military from retiring aircraft and other high-profile assets for a wide variety of reasons. The addition here of a demand that the Navy then work with the Air Force to create a formal joint service aerial electronic warfare force within their respective reserve components, which includes the National Guard, is a much more interesting development.

It is interesting to note that the Navy has run an active component Joint Airborne Electronic Attack Program in cooperation with the Air Force since at least 2011, which has seen the latter service send pilots to actually fly in Growlers operationally. The scope of that program, which is managed on the Air Force side by the 390th Electronic Combat Squadron at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island in Washington State, has expanded over the years. Air Force Capt. Aaron “Brutus” Tindall became the first member of that service to graduate from the Navy’s Airborne Electronic Attack Weapons School, also known as Havoc, essentially a Topgun program for EA-18G pilots and Electronic Warfare Officers (EWO), last year.

The Navy’s expeditionary electronic attack squadrons are uniquely focused on providing the EA-18G’s capabilities to non-naval units, especially those in the Air Force, as well as those belonging to allied and partner forces. The Growlers have unique capabilities that focus on disrupting enemy air defenses and they can integrate directly with other tactical fast-jet assets. With their next-generation jamming pods and other upgrades on the way, the fleet will experience a major leap forward in what it can offer in the coming years.

As it sits today, the EA-18G is the only dedicated fast jet airborne electronic attack asset in any of the services. The retirement of the EF-111 Raven in 1998 ended the Air Force’s organic dedicated fast-jet electronic attack capability. The Marines retired the EA-6B Prowler in 2019. Just the EC-130H Compass Call aircraft, which focus on jamming enemy communications and datalinks, provides electronic attack support within the service itself. These aircraft will be replaced by more capable and faster EC-37Bs based on the Gulfstream 550 business jet, but will still be very limited in number — only 10 will be procured to replace 14 EC-130Hs — and once again, their mission is different than the EA-18G’s.

This all comes at a time when, by every indication, airborne electronic attack is in more demand than ever. This had already made the Navy’s proposed gutting of its land-based EA-18G force curious, especially without then distributing those units’ young EA-18Gs to carrier-based squadrons.

At the same time, it is true that the airborne electronic warfare space is changing. Existing fighter aircraft are being upgraded and new ones are being built with increasingly advanced ‘digital’ electronic warfare suites of their own, which can be a big help in terms of survivability and situational awareness, in general, for their crews. Networking these assets together to fight collaboratively in the radio frequency spectrum will only make them more capable as a whole. And it’s also true that electronic warfare is becoming more distributed via the use of self-contained pods, such as the U.S. Marine Corps’ Intrepid Tiger family of electronic warfare systems, but these capabilities still are not a replacement for what an EA-18G can provide.

There has been some talk more recently about outfitting the Air Force’s new F-15EXs – the vast majority of which are expected to be assigned to Air National Guard units – with at least some of the same new electronic warfare pods being developed for the Growler. It is an interesting proposition that could take advantage of the F-15EX’s own electronic warfare suite, but there are only so many missions one aircraft and its crew can be prepared to do and the airborne electronic attack role is highly specialized and requires expertise and constant training. Still, with only 80 F-15EXs now set to be bought, this makes little sense beyond an add-on capability, not a replacement for the EA-18G.

In the future, greater use of electronic warfare-enabled decoys and other ‘air-launched effects‘ (ALEs) — especially small air-launched drones with electronic warfare payloads — will work to confuse, blind, and jam enemy air defenses in a stand-in, not stand-off nature. But these capabilities are largely complementary to the Growler, not a replacement for it. Other capabilities, like cognitive and cooperative electronic warfare, are set to only make the EA-18G more powerful and relevant on the electronic battlefield of the future. This is especially true against peer state competitors like China which is investing very heavily in the electronic warfare space, and especially in the airborne component of it.

There remains a possibility that another platform, or platforms, may be waiting in the wings or is even already operational, which could displace the EA-18G on some level. There have long been rumors about a stealthy unmanned aircraft that could provide electronic warfare support deep inside enemy territory. Basically, this aircraft could act to protect other stealthy assets as they weave their way through air defenses and just directly work to blind critical enemy air defenses and jam communications nodes even during the opening stages of a conflict.

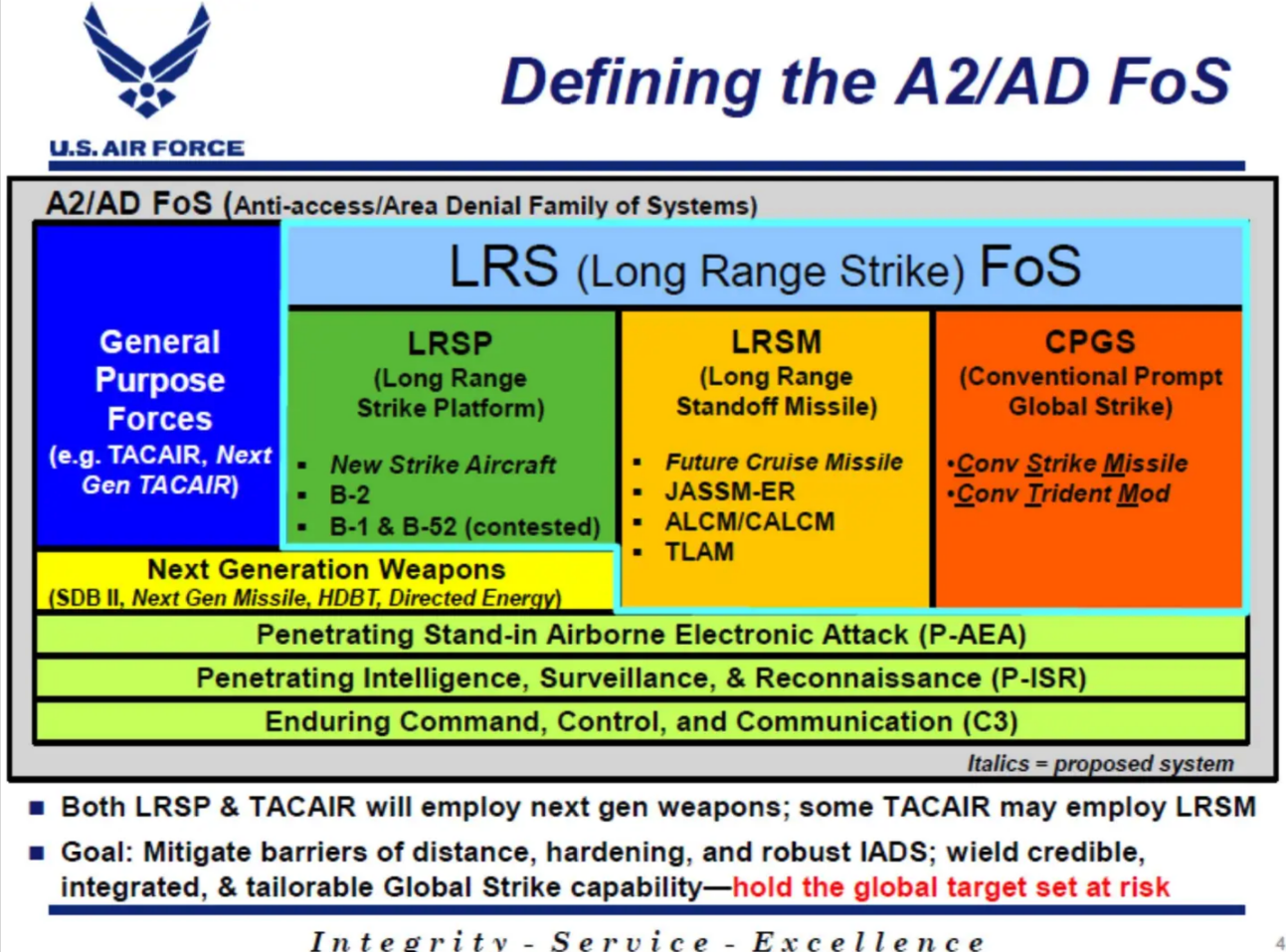

Development of such an aircraft was listed as a priority years ago as part of an Air Force strategy to negate anti-access/area-denial capabilities, most notably those being developed and deployed by China. This included a penetrating stand-in airborne electric attack capability, along with a penetrating intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance one, and enduring command, control, and communication. It’s possible that one airframe could potentially be configured to do all these things individually or even all or two of the roles simultaneously.

USAF slide

Making anything stealthy that also has to emit RF energy to complete its mission, and quite dynamically in this case, is a challenge, but leaps in active electronically scanned array (AESA) technology, along with low-probability of intercept (LPI) emissions tactics make this possible. Decades of development in providing stealth aircraft with advanced electronic warfare suites has also provided a clear path to such a capability. The potential ability to deploy small drones with jamming packages — the aforementioned ALEs — very near hostile emitters deep in contested airspace could allow the primary platform to distribute the RF emitting role to expendable drones and keep itself largely undetectable, too.

In addition, there is the emerging group of various programs for ‘attritable,’ or less than exquisite and optionally disposable, stealthy combat drones that are highly modular in nature and will be able to pack electronic warfare payloads. This can be on independent missions or when used as loyal wingmen teamed with a manned asset. Providing electronic attack, even in a stand-in, high-risk nature, would very well be part of their mission set.

Finally, both the Navy and the Air Force have Next Generation Air Dominance programs underway. These will include a manned or optionally manned highly advanced platform at the core of an ecosystem that will include various unmanned aircraft, networked weapons, and a highly survivable networking architecture. Electronic warfare will be a major component of this ‘systems of systems’ approach as these aircraft will have to penetrate deep into contested airspace. Still, even part of this capability set is at least a decade away and it won’t come all at once, but will likely be introduced operationally in stages over time.

So, yeah, there is a ton going on in the electronic warfare space, and this doesn’t even mention the employment of large swarms of lower-end drones to wreak havoc on an enemy’s air defense system.

How any of these developments play into the Navy’s original decision to ask to end its involvement in the expeditionary electronic attack squadrons and send 25 Growlers to the boneyard isn’t clear. After first seeing the budget item in question we reached out to the Navy for justification for its request, and it took well over a month to get a formal response, which sounded anything but confident and steadfast in the decision, stating:

“Navy continues to assess all of our warfighting requirements based on the changing security environment and 2022 National Defense Strategy. We are currently re-assessing our requirements for airborne electronic attack (AEA) capability and capacity – this work is ongoing and no decision has been made yet. The results of this assessment will inform the FY24 [Fiscal Year 2024] President’s Budget and the Navy will shape the disposition of these five Growler squadrons in FY24 based on that analysis.”

All told, what the future holds for the EA-18Gs and personnel currently assigned to the Navy’s five active-duty land-based electronic attack squadrons, and whether they will end up as part of a new joint-service entity run in cooperation with the Air Force, very much remains to be seen. What is clear is that this increasingly critical domain of warfare is changing rapidly and there are likely multiple capabilities in existence that remain classified but could have a direct impact on whatever decision gets made in the future when it comes to airborne electronic attack force structure.

Still, the Growlers bring a highly-deployable and employable (not something easily done with clandestine assets), proven, and very potent electronic warfare capability to the fight that remains essential to the survivability of allied assets in many circumstances and especially in a coalition wartime environment. In addition, enemy air defenses are only improving and more advanced systems that once only belonged to peer state rivals are proliferating to less predictable actors around the globe. As such, it is a bit puzzling how the aim wasn’t to expand this critical capability as opposed to shrinking it or at the very least, maintaining it.

Contact the authors: tyler@thedrive.com and joe@thedrive.com