The Air Force may be facing significant delays in replacing its aging fleet of EC-130H jamming planes. As the service tries to replace the specialized aircraft, which have been especially valuable in fighting ISIS terrorists, formal protests against its plans are mounting.

On May 25, 2017, American plane-maker Boeing announced it had lodged a complaint with the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a top federal watchdog, over how the Air Force has structured its effort to replace the EC-130H electronic warfare aircraft, nicknamed Compass Call. In March 2017, Canadian aviation firm Bombardier filed a similar notice with the GAO.

“The Air Force’s approach is inconsistent with Congress’s direction in the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act and seems to ignore inherent and obvious conflicts of interest,” a Boeing spokeswoman said in a statement, according to FlightGlobal. “We believe that the U.S. Air Force and taxpayer would be best served by a fair and open competition, and that the Air Force can still meet its stated timeline of replacing the aging fleet of EC-130Hs within 10 years.”

Each $165 million EC-130H is a modified C-130 Hercules cargo plane that carries a suite of electronic attack gear that can find and track “emitters” like radios and radars and then scramble their signals. The four engine aircraft had a cruising speed for approximately 300 miles per hour and can fly almost 2,300 miles without refueling. They are capable of refueling in midair for extended operations. Since their introduction in 1982, Compass Calls have flown in support of American operations from Europe to the Middle East to North Africa.

These aircraft have been especially critical in America’s fight against terrorists around the world. The same gear that blocks military communications can jam cell phones, too. This meant that the aircraft could help stop militants from using that method to remotely set off deadly improvised explosive devices (IED). Between March 2003 and August 2010, Compass Calls flew more than 20,000 hours over Iraq and U.S. commanders credited them with directly preventing militants from detonating at least 100 roadside bombs. Crews have put in more than 40,000 flights hours in over Afghanistan performing similar missions.

I was among the first to report on their return to Iraq to help Iraqi and Kurdish forces battling ISIS in December 2015. In January 2016, a public affairs officer with the 386th Air Expeditionary Wing in Kuwait confirmed to me that the aircraft had supported Iraq’s troops as they fought to liberate Ramadi, screwing up terrorist communications and preventing militants from alerting each other or responding quickly to new developments on the battlefield. By the end of the year there was talk that the aircraft had gone into action to knock out ISIS’ growing arsenal of small drones, which it was using to spy on friendly forces, direct artillery fire, and even drop improvised bombs on them. As of May 2017, the EC-130Hs were still flying regular missions in the country.

In February 2015, the Air Force had briefly considered eliminating half of the already small 14-plane fleet in order to free up approximately $300 million for other projects. Congress rejected that proposal and has subsequently mandated the service maintain the EC-130Hs. President Donald Trump’s first proposed defense budget, for the 2018 fiscal year, pointedly includes funding to keep all the aircraft in active inventory. Unfortunately, after more than three decades of active service, the aging planes are in need of replacement sooner rather than later.

So, at the core of Boeing’s and Bombardier’s disputes with the Air Force is the service’s plan to speed up this replacement process with as little disruption as possible to operations within the next decade. Firstly, defense contractor L-3, which has a wealth of experience from maintained the EC-130H fleet for years, has received contract to effectively port over the existing Compass Call system into a new aircraft. However, instead of holding a separate competition to select who will get to build this plane, the New York-headquartered firm will be the one choosing the new airframe.

The U.S. Army and Air Force have used similar methods to rush surveillance aircraft into combat since the mid-2000s. The contracts for these so-called “quick reaction capabilities” focused more on what particular sensors commanders in the field wanted overhead rather than the plane carrying them. In many cases, the services were perfectly happy to let contractors retain complete ownership of their aircraft and even the mission equipment, arrangements that are still known as “government-owned and contractor operator” and “contractor-owned and contractor operated,” or GOCO and COCO. By 2010, the Army had two different types of aircraft carrying the Constant Hawk electro-optical system in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as three kinds of planes lugging the imagery and signals intelligence equipment associated with the Medium Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance System (MARSS) in both of those countries.

But this may be the first time the U.S. military has ever chosen to take this route when buying what will be wholly government-owned system outright. “I can’t give you an example specifically of a contractor picking the aircraft,” Air Force Lieutenant General Arnold Bunch, the service’s top acquisition official, told Defense One in an interview that described the decision as “unprecedented.”

Air Force officials insist this is a viable method of doing business that serves its very immediate needs and still gets taxpayers a good deal. Boeing and Bombardier have countered by complaining to GAO that this almost guarantees Gulfstream and its G550 business jet will get the contract for new electronic attack aircraft. Bombardier wants to put its Global 6000 business jet the running. The Air Force already has a variant of Bombardier’s Global Express family, known as the E-11A, in service to carry the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) data relay system. Boeing would like to offer a version of its venerable 737 airliner, a derivative of which is flying with the U.S. Navy as the P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol plane. Multiple foreign air forces fly 737-based airborne early warning aircraft, as well.

The G550 and Global 6000 are roughly equivalent aircraft, with very similar dimensions and cruising speeds. Gulfstream says its base aircraft has an unrefueled range of approximately 6,750 miles, 750 miles more than Bombardier’s plane, but that could easily change with the Compass Call systems installed. Boeing’s 737-based Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) is significantly larger, but still has a range of approximately 6,200 miles. The P-8 variant of the 737 has a range of roughly 4,500 miles. Still, a 737 derivative will have a lower ceiling (by as much as 10,000 feet) than its business jet competitors.

Since L-3 has not yet had a chance to choose any particular plane, the government watchdog’s opinion was that Bombardier’s protest was “premature,” according to FlightGlobal. It is entirely possible the oversight entity will reach the same conclusion in response to Boeing’s challenge.

That’s not to say the concerns aren’t reasonable. L-3 is already working with Gulfstream on Air Force’s separate effort to recapitalize its E-8C Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS) radar aircraft as part of a Northrop Grumman-led team. Northrop Grumman, which developed the original JSTARS equipment, plans to use the G550 as the host aircraft for its improved system. The company already uses one of the jets as a developmental testbed.

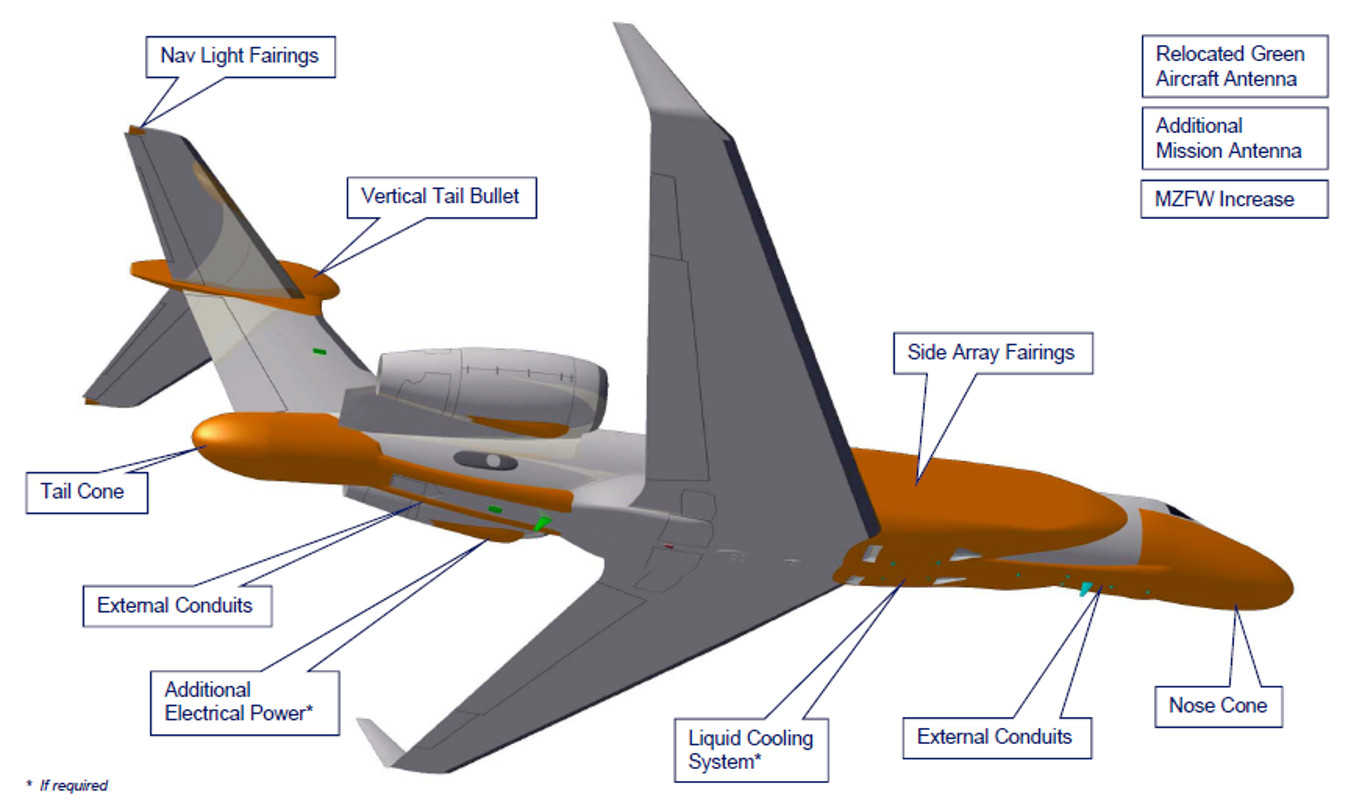

On top of that, the Air Force has already expressed interest in using a variant of Gulfstream’s G550-based Conformal Airborne Early Warning (CAEW) design as the Compass Call replacement. In its fiscal year 2017 budget proposal, the service outlined a plan to buy six electronic attack versions it referred to as EC-37Bs. This dovetailed with the idea of junking half of the EC-130Hs, which would have created a mixed fleet of Compass Call aircraft.

At the time, the Air Force suggested this would also be a cost-effective move, as it already had nearly 10 C-37A executive transports, which would share many of the basic aircraft components, such as the engines, and reduce requirements for specialized maintenance and logistics support. The Navy had just bought a CAEW variant to support test range operations, too.

In addition to refusing to approve scrapping any existing EC-130s, Congress also ultimately balked at this idea. As a result, the Air Force refocused its effort and decided to go down the current path of simply handing the final decision on what aircraft to use over to L-3. It is insistent now that this is the best way to proceed.

“We made this decision after looking at all the options – laying out pros and cons, looking at a variety of different methods that we thought we could work our way through this,” Lieutenant General Bunch said during his discussion with Defense One. “You can’t really call an aircraft a subcomponent, but in this case, the real technology stuff and everything else is the guts. It’s what’s inside the EC-130 platform and we’re buying something to carry it.”

The big question is whether Congress, and any members who might be inclined to be especially supportive of Boeing and Bombardier’s participation in the program, agrees with the Air Force’s assertion. In the meantime, the old EC-130Hs will have to continue jamming terrorists and militants on the front lines.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com

Update 5/26/2017: The original version of this story used the performance specifications of Boeing’s standard 737-700 airliner for comparison. It is unlikely that the company would offer this variant as a contender for the new Compass Call platform. The piece has been updated with BBJ and P-8 metrics.