Since its first deployment in 2009, the EA-18G Growler has become the premier airborne electronic attack platform in the United States military. So it came as a surprise to many when the U.S. Navy published a document highlighting various aspects of its Fiscal Year 2023 budget proposal and it called for the decommissioning of all five of the non-carrier-based Growler squadrons, which have a total of 25 aircraft.

It reads, in part, as follows:

Decommission Five Active Component Expeditionary Electronic Attack Squadrons (VAQs). Divests of all non-carrier-based EA-18G Growler support of joint force requirements for tactical airborne electronic attack (AEA) capability and capacity. Divestment involves decommissioning five Growler squadrons, collectively consisting of 25 airframes and approximately 1,020 associated officer and enlisted billets. Military end strength will be reduced by half in FY 2024 and fully in FY 2025. Associated aircraft will be placed in long-term preservation at the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG). Half of the aircraft will be inducted in FY 2024 and the remainder in FY 2025. (FY 2023: $0.0M/ FYDP: -$807.8M)

The five squadrons are known as Expeditionary Electronic Attack Squadrons, or Expeditionary VAQs, and uniquely support U.S. Air Force and Navy shore-based operations. While the aircraft retain the ability to operate from aircraft carriers if needed, their crews are not trained to do so.

The request to decommission these units comes at a rough time considering that in late March, six Navy Growlers from VAQ-134, the “Garudas,” were rapidly deployed from their home base at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island in Washington and arrived at Spangdahlem Air Base in Germany. They were sent there in order to bolster readiness and NATO’s collective defense posture after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Navy Capt. Christopher M. Bahner, who serves as commander of Electronic Attack Wing Pacific, stated about the deployment: “Expeditionary EA-18G squadrons integrate with joint and coalition forces to provide our commanders capabilities to defend our forces in all potential phases of operation, while allowing our Carrier Air Wing EA-18G squadrons to remain at sea, defending freedom of navigation with our carrier strike group teams.”

It is no secret that the Growler is in high demand from combatant commanders. When the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) left on its first deployment in the Indo-Pacific carrying F-35Cs, it also had two extra EA-18Gs on hand, bringing the carrier’s Growler fleet to seven compared to the normal five seen on most deployments. The extra EA-18Gs were part of the carrier’s ‘plussed-up’ airwing for the historic deployment.

According to Rear Admiral Dan Martin, commander of the Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group, the pairing of the F-35C and EA-18G complemented each other. He told reporters “It’s (F-35C) a brand new aircraft with advanced sensors. So we like to pair them with the Growler to complement each other and when you fly around that theater, collection operations become a big deal.” Speaking about the Growler he added, “We’re advocating for more because we saw the value of that aircraft in theater.”

After the retirement of the U.S. Air Force EF-111 Ravens in the mid-1990s, the expeditionary EW mission fell to the Navy and Marine Corps which operated the EA-6B Prowler. Both services have since retired the Prowler with the last Marine EA-6B squadron shutting down in 2019. Since then, the Navy has been the sole source of fast jet electronic warfare aircraft for the U.S. military and has been working hard to upgrade the Growler. Just last year, the service announced a new contract modification to modernize sensor hardware and software for the EA-18G.

Sending 25 of these highly-capable and in-demand aircraft into storage in the desert seems to make little sense when the Growler fleet is about to become even more effective with the introduction of the Next Generation Jammer pods, which will replace the maintenance-intensive and long-serving ALQ-99 tactical jamming pod system. These new pods offer a quantum leap in capabilities over what came before.

The EA-18G is a major force multiplier. In essence, it allows other aircraft to survive on the modern battlefield, one that is increasingly being populated by highly potent integrated air defense systems. In fact, the survival of even stealthy aircraft can often depend on electronic attack support, like what the Growlers provide.

Beyond the new jamming pods, the Navy’s EA-18Gs are only set to become more capable in the future thanks to a Block 2 upgrade program. This will include, among various other things, an advanced “cognitive electronic warfare” capability that will make use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technology. You can read more about cognitive electronic warfare as a general concept, which is focused on automating and otherwise speeding up various aspects of electronic warfare, here.

On top of their existing and planned future capabilities, the Navy’s 161-strong EA-18Gs fleet is very young. The jets, on average, have each only flown 2,465 flight hours out of their expected 7,500-hour service lives, which can be extended even further, if need be.

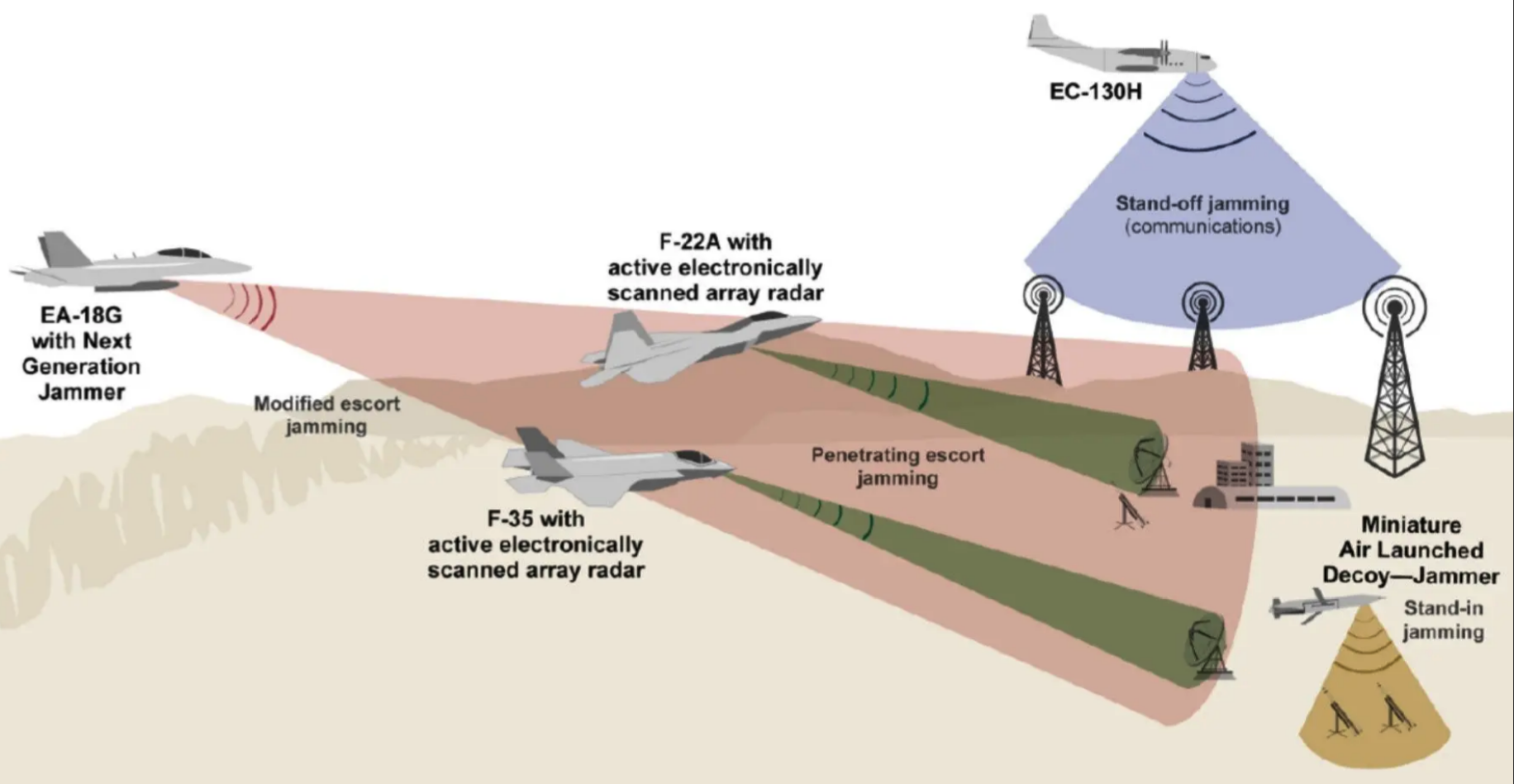

At the same time, electronic warfare and the suppression of enemy air defenses will be key to any future battle with a near-peer adversary like China, so one has to wonder if the USAF has some new capability, such as a penetrating unmanned aerial vehicle that will at least offset some of the capabilities and capacity lost by canning the expeditionary Growlers. The EA-18Gs cannot fly deep into enemy airspace like a stealthy drone could, allowing the latter to provide a different flavor of electronic attack that includes stand-in jamming. Swarms of small expendable drones will also provide this capability in the future, but those are slow and limited in their abilities. On the other side of the performance envelope is the Miniature Air-Launched Decoy (MALD), which now includes an active electronic warfare component.

It’s also true that combat aircraft themselves are being equipped with far more capable ‘digital’ electronic warfare suites, many of which utilize the aircraft’s powerful AESA radar in an electronic warfare mode. But the more traditional jamming support the EA-18 can provide, especially over longer distances and against multiple threat emitters, is complementary to these capabilities.

The USAF is also working to revitalize its small fleet of Compass Call electronic warfare aircraft, which is mainly aimed at jamming communications. Its new Gulfstream-based EC-37 platform will far outperform the C-130s it will replace. It’s very possible it will also be more capable against radars and other air defense nodes than its predecessor, as well. Still, this is a tiny fleet and is not really optimized for tactical jet operations.

We also know that the Air Force was eyeing integrating the Next Generation Jammer pods on its own aircraft, such as the F-15EX. This very well could be a justification for drawing down these squadrons, but the specialization they provide will be impossible to replace by multi-role fighter units with many other missions.

We have reached out to the US Navy regarding the justification for decommissioning these squadrons but have not yet gotten a response.

Stay tuned!

Editor’s Note: This story was published on April 25, 2022, but a site-related issue subsequently led to a change in the timestamp.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com