The U.S. Navy recently put in a rush order for new counter-drone systems that use laser-guided 70mm rockets as their effectors to help defend American forces in the Middle East. The Electronic Advanced Ground Launcher System (EAGLS) is very similar in form and function to U.S.-supplied VAMPIREs that Ukrainians are now using in combat. The purchase of the EAGLS came just days ahead of Iran’s unprecedented missile and drone strikes on Israel, which have only added to long-standing concerns about uncrewed aerial and other threats to U.S. forces in the region.

Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) announced on April 12 that it had awarded a firm-fixed-price contract with a not-to-exceed value of $24,186,464 to MSI Defense Solutions for the purchase of five EAGLS Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (C-UAS). This sole-source deal also includes various ancillary items and training support.

EAGLS uses laser-guided 70mm Advanced Precision Killer Weapon System II (APKWS II) rockets, as seen in the video below, to knock down drones.

“This contract action is” in response to an urgent need to respond to “emerging and persistent UAS threats in the United States Central Command (USCENTCOM) Area of Responsibility (AOR),” according to an associated Justification and Approval document the Navy released. U.S. government agencies have to submit justification documents like this in order to receive authority to award contracts without going through normal competitive bidding processes.

“Immediate contract award is critical due to the urgent need of ongoing operations in the USCENTCOM AOR,” according to the J&A document. “If the immediate procurement is not made, U.S. Forces will not receive necessary critical C-UAS systems as required for capability in theater.”

The J&A says that the goal is for the first EAGLS to be fielded within 30 days of the contract award.

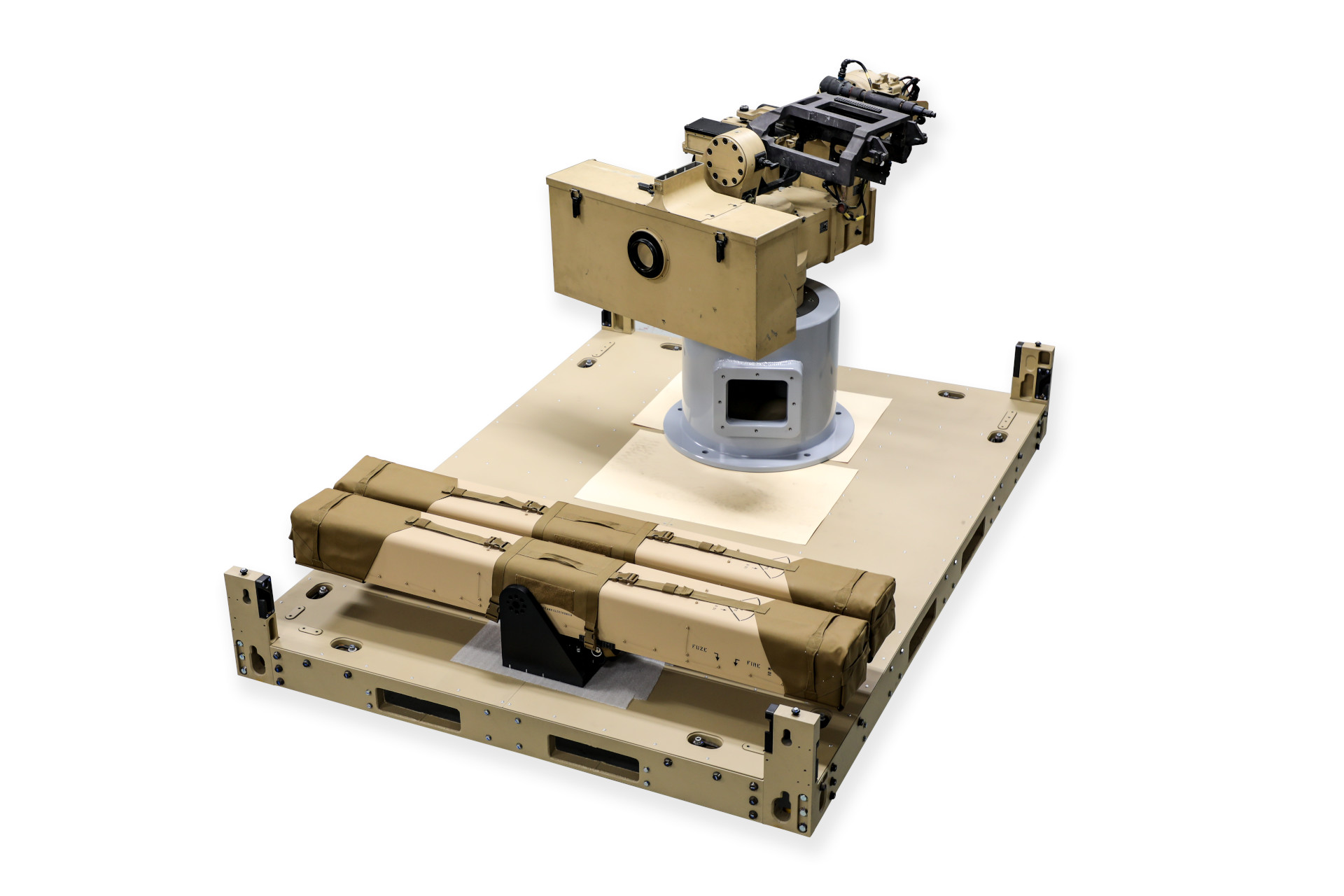

EAGLS is a self-contained system that consists of three main parts: a version of the Commonly Remotely Operated Weapon Station II (CROWS II) fitted with a four-round 70mm rocket launcher loaded with laser-guided Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) rockets, a sensor turret with electro-optical and infrared cameras, and a small radar array. The system is designed to be deployed in either palletized or vehicle-mounted forms. MSI’s website shows a version installed mounted on a pickup truck-style variant of the 4×4 Humvee light utility vehicle, as is seen at the top of this story.

The radar used with EAGLS is a Leonardo DRS RPS-40, a member of the company’s Multi-Mission Hemispheric Radar (MHS) family. This radar, which is a compact S-band active electronically scanned array (AESA) type, can detect targets up to 10 kilometers (just over 6 miles) away, according to the manufacturer, though this would be dependent on their size and other factors. The RPS-40 is an increasingly popular radar that several other counter-drone and short-range air defense systems make use of, including the U.S. Army’s Mobile Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD) variant of the 8×8 Stryker wheeled armored vehicle.

MSI’s offering is one of a growing number of counter-drone systems utilizing APKWS II rockets and otherwise with similar overall configurations that are designed to be platform agnostic. This includes L3Harris’ VAMPIRE, examples of which NAVAIR has directly helped deliver to Ukraine, and that have now proven themselves in combat.

The U.S. Army has also been working on a containerized counter-drone system that makes use of a modified CROWS II with a four-round 70mm rocket launcher and a different MHS-series radar from Leonardo DRS, as well as a camera-equipped sensor turret, which you can read more about here.

The addition of the radar gives the EAGLS additional capability and flexibility over VAMPIRE configurations that have been seen to date, the only sensors in which are turrets with electro-optical and infrared cameras. A radar like the RPS-40 gives operators of systems like EAGLS more advanced warning of potential threats and better data about where they are coming from. It is unclear whether EAGLS’ 70mm launcher can be automatically cued to the system’s radar and/or its senor turret, but this seems likely and would be highly desirable.

The addition of the radar does mean that EAGLS puts out additional radio frequency signals that more advanced enemy forces could use to detect and locate its position. The sensor turret does not give off a passive target detection and engagement capability that could be used even if the radar is switched off to reduce the system’s signature in the electromagnetic spectrum.

APKWS II rockets can be employed against ground targets giving C-UAS systems based around these weapons an inherent surface-to-surface attack capability. Originally designed as air-to-ground munitions, these rockets also have a demonstrated capability in the air-to-air role against drones, as well as cruise missiles.

The laser-guided rockets are modular and low-cost, with the guidance section designed to slot in between existing standardized 70mm warheads and rocket motors. The unit cost of the APKWS II guidance section is around $25,000, with the warhead and rocket motor together typically only costing a few thousand dollars more depending on their exact types, according to Navy budget documents. For comparison, the cost of a single Coyote Block 2 interceptor, another counter-drone weapon currently deployed to help protect U.S. Forces in the Middle East, is reportedly roughly around $100,000. Current generation Stinger short-range heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, which include new features to improve their effectiveness against drones, have a unit cost of around $400,000.

NAVAIR has previously announced that it has been working with the APKWS II’s prime contractor, BAE Sytems, on the development of a new proximity-fuzed warhead specifically optimized for use against drones.

Where exactly in the Middle East the EAGLS might be headed and what specific threats prompted their purchase is unknown. However, Navy Rear Adm. Stephen Tedford, head of NAVAIR’s Program Executive Office for Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons (PEO U&W), made comments at the annual Sea Air Space conference last week that suggest these systems could be headed to bolster counter-drone defenses at Navy and other U.S. military facilities in the Persian Gulf.

“A lot going on in the space of with APKWS in regards to counter-UAS services. So, with everything that’s been going on in the Red Sea that you’re all familiar with in the news, APKWS is providing us a much more affordable approach to getting after the counter UAV [uncrewed aerial vehicle] space,” Tedford said. The situation in the Red Sea that Tedford was referring to is the ongoing anti-ship campaign by Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen. The Houthis have used ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as drones, to attack commercial vessels and foreign warships in the region.

“We’re working on a system now that will be deployed in [the] 5th Fleet [area of responsibility] to provide base security and force protection for our services in the [Persian] Gulf.” Tedford continued.

U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) and the U.S. 5th Fleet have their headquarters in Bahrain right on the Gulf. U.S. forces also operate from several major air bases, as well as smaller facilities, across the Arabian Peninsula. Vessels sitting in port are particularly vulnerable to drone strikes, as has been underscored by the Houthi’s recent targeting of Israeli warships in Eilat on the Gulf of Aqaba.

There is still a possibility that EAGLS could be deployed elsewhere in the Middle East outside of the Persian Gulf. U.S. forces are forward-deployed at a constellation of larger bases and smaller sites across the region, including ones in Israel, where there are also drone threats. In addition, the Navy recently expressed interest in new ways to rapidly add counter-drone defenses to its warships themselves. A palletized system like EAGLS could be an option for helping to meet that demand, as well.

In his comments last week, Tedford also cited the value of experience that NAVAIR has gained from working with Ukraine on the VAMPIRE system. The conflict in Ukraine has helped bring the threat posed by drones into the mainstream consciousness.

However, the threat posed by drones, including to U.S. forces at home, as well as abroad, is anything but new, as The War Zone has been highlighting for years now. Just in January, Iranian-backed proxy forces killed three U.S. servicemembers at a forward operating base in Jordan with a kamikaze drone attack, highlighting the very real danger even lower-tier uncrewed aerial system present.

Potential drone threats in the Gulf region have only grown in the wake of Iran’s unprecedented missile and drone strikes on Israel over the weekend. Authorities in Tehran have threatened to retaliate against U.S. forces across the Middle East if they aid their Israeli counterparts in any future strikes on Iran. Any such Iranian response could come in full or in part through its proxies, as well. U.S. bases in the Gulf region are well within range of kamikaze drones, as well as missiles, that the Houthis have in their arsenal.

It is worth noting that an order for five EAGLS represents a relatively small additional counter-drone capability. The overall nature of the acquisition also seems to reflect that the U.S. military is still playing catch-up to the drone threat, even in the face of ever-growing evidence of its seriousness, including the recent attacks on Israel. U.S. forces, including warships offshore, combat jets, and ground-based air defenses, were heavily engaged in defending Israel from that incoming barrage of missiles and drones.

Overall, the new EAGLSs look set to provide important additional counter-drone capabilities to U.S. forces in the Middle East, but the purchase of these systems also underscores the need for much more capacity in this regard.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com