Shortly before making history by launching the first ALTIUS-600 drone ever to fly into a hurricane, the NOAA WP-3D Orion, nicknamed Kermit, was rocked by turbulence so violent after an eyewall penetration that many aboard suffered air sickness. “A lot of people had barf bags filling up,” Joe Cione, Lead Meteorologist for New Technologies at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory, told The War Zone Thursday morning. The flight was so turbulent that NOAA Hurricane Hunter Nick Underwood, who was one of the 18 people aboard the flight, called it “the roughest flight of my career so far.”

“We got slammed pretty hard,” said Cione, who has flown some 150 eyewall penetrations in about 25 such flights.

But Nick Liccini and Patrick Sosa, the two staffers from AREA-I, the Marietta, Georgia company that makes the ALTIUS-600 “were real heroes too, because both of them were sick and not feeling well at all and they still managed to do the job.”

That job was to help guide the ALTIUS-600 – a 40-inch-long, 23-pound drone with a 100-inch wingspan when deployed – into the eye of Hurricane Ian to help fix its center and gather other data needed to help gauge the intensity and track of the massive, deadly storm.

But it was no slam dunk, Cione said.

The eyewall was in the middle of rearranging itself, and in an oval shape, instead of perfectly round, “which was a sign that the storm was intensifying while we were there. It was pretty unnerving conditions.”

But thanks to the skill of the aircrew and the sturdiness of the airframe designed for such situations, Kermit made it through and the drone was launched. It turned out to be a highly successful first launch of the drone that provided valuable insights including locating the true center of the hurricane.

“We managed to launch the drone and babysat it for a few minutes so it could get its bearings. And we did all that under conditions where we had just some very severe turbulence.”

The flight was so rough that NOAA waived off further eyewall penetration attempts while still monitoring Ian, collecting “operationally valuable data” and providing telemetry support for the drone.

But the ALTIUS-600 – a version of which is also being tested in the U.S. Army’s Air Launched Effects (ALE) program – kept flying for two hours after being launched, providing data from inside the storm that Kermit could not. And the crew inside Kermit was able to maintain communications with the drone, using a datalink, from as far away as 125 nautical miles.

“The drone was in there and we were outside the winds while the drone was measuring what it could while we were safe and away from the most violent aspects of that storm.”

Ian slammed into the Fort Myers area of southwest Florida Wednesday as a massive Category 4 storm with winds of up to 155 mph, just shy of a Category 5 hurricane.

Several people have already been confirmed dead, with many more fatalities expected.

Hurricane Hunting Started With A Wager

Aircraft have been flying into and around and above hurricanes for decades. The first such flight was actually flown as the result of a bet.

“In 1943, pilots taking part in flight training using instrument panels ribbed their instructor into betting on their new flight training, as flying exclusively with instruments was introduced in the 1940s,” according to weather.com.

Hurricane hunting flights have evolved tremendously since then.

The U.S. Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron (WRS) situated at Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, remains the U.S. government’s main hurricane hunting arm. The unit has specially configured WC-130 aircraft.

The U.S. Navy stopped contributing to the hurricane hunting mission in 1974, according to NOAA.

The 53rd WRS aircraft also flew into Ian, which you can watch in the video below.

NOAA operates three hurricane hunter aircraft out of its Aircraft Operations Center in Lakeland, Florida, all given nicknames of Muppet characters. NOAA flies two WP-3D Orions, nicknamed Kermit and Miss Piggy, and a Gulfstream IV-SP, nicknamed Gonzo. The agency has a number of other smaller aircraft for other weather surveillance purposes, too.

Like the WC-130s, the Orions generally fly into storms at between 8,000 and 12,000 feet.

The Gulfstream IV, meanwhile, flies over and around storms, cruising at about 45,000 feet.

All those aircraft drop devices called dropsondes – cylindrical cardboard tubes filled with sensors measuring air pressure, temperature, humidity, wind speed, and wind direction. The data helps determine how strong a storm is and where it is likely headed.

But the dropsondes only offer a limited snapshot of the atmospheric conditions. At 45,000 feet, for instance, the dropsondes have about 16 minutes before they hit the water.

Weather scientists have long wanted to collect data from much lower altitudes and for far longer time periods. But it is far more dangerous to fly into a storm just hundreds of feet off the water, said Cione.

“We have some remote sensors that measure directly below. But we really have no way to get continuous measurements in that boundary layer environment, which is where the air meets the sea.”

So NOAA has turned to drones, because they are expendable.

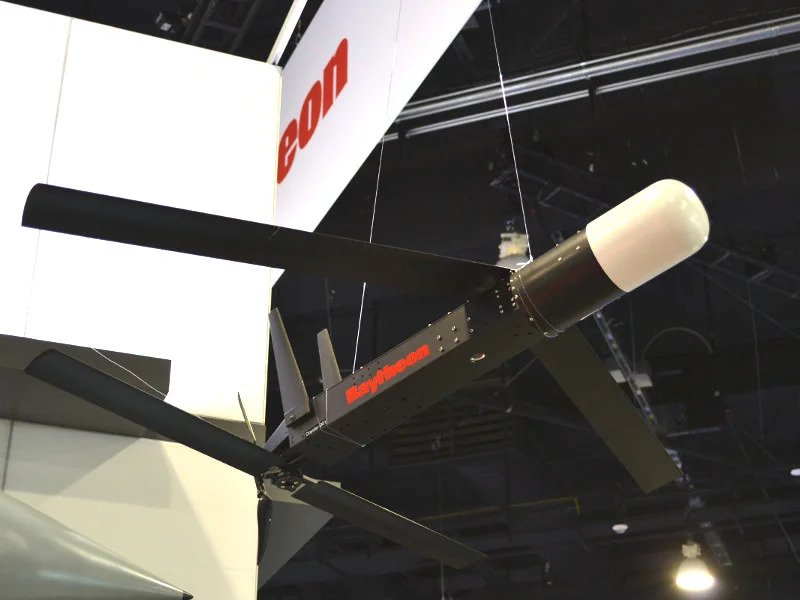

NOAA’s first use of the Raytheon-made Coyote drones was part of the observation of Hurricane Edouard in 2014. The agency had purchased the drones with funding from the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, which caused severe damage to the coasts of New York and New Jersey in particular.

In 2016, NOAA began receiving improved Coyotes from Raytheon. The biggest improvement was an increase in how far away the drones could fly from the controller on the WP-3Ds. The latest models can operate up to 50 miles from the host aircraft and fly for approximately one hour with the research sensor payloads.

In 2017, as Hurricane Maria made its way toward the Caribbean and North America, NOAA scientists launched Coyote drones into these hard-to-reach areas of the storm to gather vital information, highlighting just one of many emerging roles for expendable unmanned aircraft.

Raytheon offered the seven-pound Coyote as a lightweight, low-cost platform for a variety of roles. Personnel can get the drone airborne from on the ground, on a ship, or on board an aircraft. After launch, a six-foot wide main wing, two rear stabilizers and twin vertical tails all pop into place, giving the pilotless aircraft a distinctive look.

Between Sept. 23 and 24 of 2019, NOAA’s WP-3D Orion research aircraft dropped a total of six of the small remotely operated aircraft into Maria’s “eyewall,” a boundary layer between the eye and the rest of the storm where the weather is most severe and winds can reach speeds of 200 miles per hour or more, according to manufacturer Raytheon. The Coyotes gathered air pressure, moisture, temperature, and wind speed and direction data during the flights.

You can read much more about that in our coverage here.

Successful Mission

The ALTIUS-600 is the latest and most capable iteration of this concept.

Developed by AREA-I, ALTIUS-600 is part of the ALTIUS family of autonomous tube-launched drones or Air Launched Effects (ALE) “that are available on-demand and operational within minutes,” according to the company’s website.

They can also be launched from the air, sea, and ground from systems like the Common Launch Tube (CLT), Pneumatically Integrated Launch System (PILS), and other launch systems.

To date, ALTIUS-600 has been launched from a variety of aircraft, including UH-60s, C-130s, AC-130s, UH-60s, P-3s, and civilian airframes, as well as ground vehicles.

They have a cruise speed of 55 knots, a dash speed of 90 knots, and a cruising range of 220 nautical miles. They can stay aloft for hours.

Cione said his team worked with AREA-I to develop a drone that can fly “very, very low, a couple of hundred feet” off the surface at altitudes “otherwise too dangerous for manned aircraft.”

The rationale is that the “boundary layer right near the surface is where we all live, right? That’s where our buildings are. So we want to know, especially with the winds, what’s going on down at that altitude. And to do that more accurately, we need more measurements and these drones can give us those measurements at very unsafe altitudes in the most dangerous parts of the storm.”

NOAA successfully test flew the ALTIUS-600 in far calmer weather conditions earlier this year.

Cione, the AREA-I crew and weather scientists Jun Zhang of the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute For Marine And Atmospheric Studies at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory and Josh Wadler of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University turned that experiment into reality on Wednesday.

All things considered, Cione said it was an overwhelming success with some happy operational surprises.

“We’ve had it fly as long as 3.5 hours, but yesterday, we had some technical issues,” he said. “We’d lost communication for a little bit. The drone was sometimes flying against the wind in the eyewall which was amazing. We certainly weren’t trying to do that. But at times it was doing that. So that was not an energy-efficient way to go. That’s why we got about two hours instead of three hours or maybe even longer than that.”

One of those most interesting and promising aspects of the operation was the autonomy ALTIUS-600 was able to leverage.

“When we launched that aircraft, we said ‘go find the max winds.’ And artificial intelligence code was written for that thing to understand how to do that.”

Other than some directional commands, the ALTIUS-600 operated autonomously, even after Kermit moved out of the hurricane’s eye.

“We also had an algorithm in there so it would go in and go sniff out the center of the storm because we were in the eye at first. So it did a center fix which the P-3 normally does, and does do well, but we wanted to see if a drone could do it. And I haven’t looked at the data yet, but we did get a center fix on it, which is the first time.”

That, he said, is an important milestone, providing information the National Hurricane Center and other modeling centers want, “because not only can that help us with the atmosphere and help us with intensity, but if we can pinpoint where it is much with great accuracy, that information can also impact storm track on short timescales over 24 hours or so. Like right before landfall.”

Cione said Wednesday was just the beginning.

“We’re going to be putting a turbulence probe on there next year,” he said. “Remember, this is the first flight we’ve ever done. So this is sort of a prototype-ish kind of mission.”

ALTIUS-600’s Military Cousin

In its primary military role, the ALTIUS-600 is one of the standouts among an increasingly diverse universe of highly flexible expendable drones. The ALTIUS-600 can be configured for surveillance, electronic warfare, decoy, and kinetic (equipped with a warhead) missions. It can also pair with a flock of other ALTIUS-600s to work as a highly adaptive swarm.

The ALTIUS-600 took part in the Army’s 2022 Experimental Demonstration Gateway Exercise (EDGE 22) held in May at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. Flying in a swarm of 28, each was equipped uniquely to conduct detect, identify, locate and report back enemy positions. The swarm then simulated what the Army is calling a “stimulate, hunt, kill and assess tactic.”

You can read much more about EDGE 22 and the use of the ALTIUS-600 in our story here.

These drones, and future ALTIUS models destined for combat, will increasingly be used in an air-launched form, to work collaboratively with manned platforms and especially helicopters. They will work to help increase the situational awareness of aircrews and to protect them by working as stand-in jammers, decoys, and as deadly weapons in their own right.

Regardless of their military applications, NOAA’s use of drones to gather exciting new data about hurricanes that could end up saving lives is just another reminder of the changing reality of unmanned aviation and all the advantages it brings.

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com