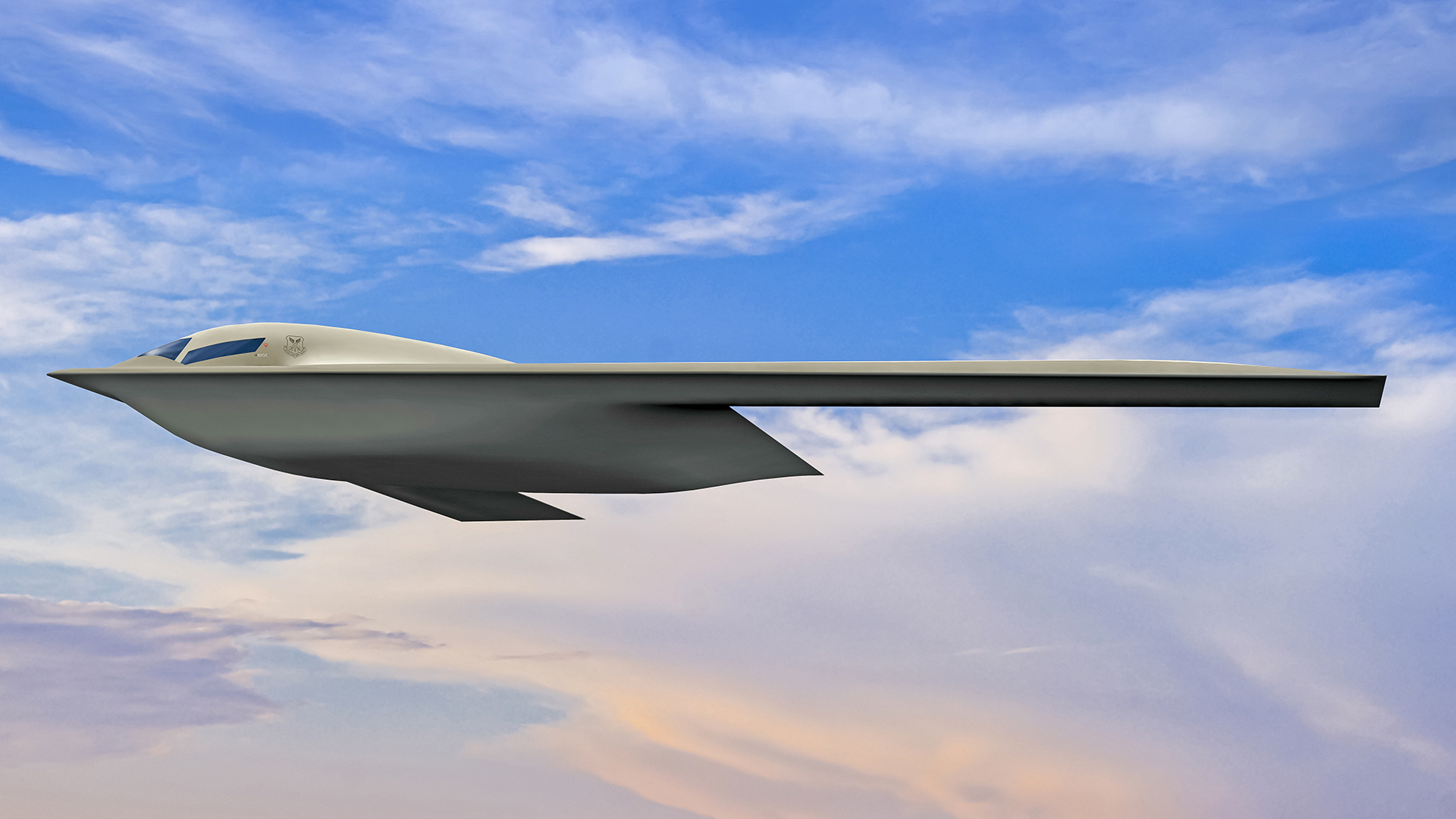

Big, turbulent shifts are underway in the U.S. military as those in charge try to rebalance future capability wants against accessible combat capacity today. For instance, a reduction and reshuffling of types are planned across the U.S. Air Force’s tactical jet fleet in the decade to come, and both the U.S. Navy and the Air Force are pivoting to what comes next in terms of tactical airpower in the form of their Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) initiatives. Yet long-range combat aviation is arguably under the most pressure. A new target of building 149 B-21 Raiders is taking shape, held up by the hope that what’s left of the B-1 fleet will stay solvent long enough to be replaced by some of those new stealth bombers. At the same time, the B-52 is slated to soldier on for decades to come, hopefully with new engines, but even that initiative is hitting financial headwinds.

Even if these plans come to fruition, there will still likely be a long-range strike deficit as adversaries enhance their anti-access capabilities. As such, it’s fairly clear that the Department of Defense (DoD), as a whole, isn’t nearly as well equipped as it needs to be today should it get into a shooting match where long-range airpower becomes absolutely essential, such as during a war in the Pacific, and it will likely still struggle to meet demands in the decades to come.

Yet there is one airframe in the inventory today that seems strangely overlooked for its potential to alleviate some of this pressure, as well as to help nullify other major pressure points among the DoD’s collective air combat inventory. Its economy, serviceability, extreme flexibility, and its ability to play a major role in any type of future fight the U.S. enters into, including one with a towering peer-state adversary like China, as well as playing critical roles in peacetime, is unrivaled. The aircraft I am referring to is Boeing’s P-8 Poseidon, but not in its current configuration.

Untapped Opportunity

In most regards, the P-8 has been a major success. It is a versatile tool that leverages the most understood airliner airframe on earth at its core. While maritime patrol may be its central functionality, it has already proven itself well suited for electronic intelligence gathering and for toting outsized sensors for specialized missions. There is a very strong argument to be made that there are not enough P-8s slated for the Navy’s inventory in order to pick up where the P-3 Orion left off, and especially in a new era of expanded submarine warfare, but that is not the focus of this piece.

While the P-8’s ability to fulfill other roles is convenient, those other functions distract the relatively tiny fleet of a planned 128 examples from its highly critical primary mission set. In fact, the aircraft has so much latent potential, which is now slated to increasingly get unlocked via the addition of a slew of new weaponry and podded systems, that one can only imagine maritime patrol will continue to compete with everything else it can do. And since a P-8 can only be in one place at one time, regardless of how capable and versatile it is, this is a problem that seems to be demanding some sort of solution. That solution could, and very well should, go beyond the Navy.

Instead of thinking just about how the Navy can buy more P-8s as they are configured today, the Air Force, possibly in cooperation with the Navy, should also be examining the idea of buying a variant of the P-8 that is stripped down to its bare essentials. In effect creating an off-the-shelf, highly economical, and sustainable arsenal ship and sensor platform that can perform a huge array of tasks—submarine hunting and traditional maritime patrol not being one of them.

What I am proposing here is an ‘RB-8’ of sorts. A P-8 stripped of all its maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare gear, aside from the relevant parts of its communications capabilities, defensive aid systems, FLIR turret, and outstanding electronic support measures (ESM) suite. In its nose, an off-the-shelf scalable fighter AESA radar would be installed. A substantial amount of its internal volume would be left empty, aside from packing as much additional fuel onboard wherever possible and housing a trio of open-architecture mission specialist/weapon systems officer consoles behind the cockpit. It would also retain the P-8’s current sonobuoy launchers and racks.

What’s key here is that the P-8’s development is totally paid for. Its evolution continues with new weapons and other capabilities being added. With seven allied export customers now taking part in the program, sustainment of the type will be economical as it can be for decades to come.

A fully-equipped P-8A has a unit cost of $175 million, and a 737-800 costs roughly $85 million new. One could imagine an additional large block buy of this stripped-down variant could be had somewhere in between, let’s just throw a number on it, say $130 million. What the total force would get for that price tag, roughly just 50% more than the price of an F-35A, would be absolutely outstanding. In fact, one could argue that it would be the most flexible, economical, and relevant combat aircraft in the entire arsenal.

Standoff Weapons Truck

With this whittled-down base ‘RB-8’ model, the Air Force would get an aircraft capable of executing electronic surveillance missions just like the P-8 does today. This would free up the Navy’s P-8s for more maritime patrol-related tasks—especially anti-submarine warfare operations. But where the aircraft would really shine is in its ability to adapt to any combat scenario.

The P-8 has four wing pylons. Each of these stores stations, which are rated at 2,500 pounds, are able to carry standoff cruise missiles, such as AGM-84 Harpoons and SLAM-ERs, and eventually the stealthy Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM). If the P-8 can carry LRASM, the RB-8 can carry its land-attack sister weapon, the Joint Air-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), as well as LRASM, and more types of advanced air-launched standoff weapons are on the way. But unlike a fighter, it can carry those weapons over thousands of miles from an aerial refueling tanker, like U.S. bomber aircraft.

Four JASSMs delivered for standoff attacks by fighters flying from bases thousands of miles from their launch points in the Pacific would require a large tanker commitment. The RB-8 would require a fraction of those resources and it could actually execute that mission with near-737 efficiency, which is far cheaper and more reliable than a bomber or even a jet transport aircraft.

While using transport aircraft to chuck JASSMs at enemy targets by deploying them via air-dropped pallet is certainly a worthy endeavor to continue to explore, in reality, during any major conflict, especially one in the Pacific, America’s airlift fleet will be pushed to its breaking point just trying to keep up with the basic logistics needed to sustain the war effort. So, unless you buy many more expensive transport aircraft—of which no Western long-range jet-powered types are in production—it’s questionable just how useful this capability will be, at least in terms of sustained combat capacity.

Also, aside from the special operations MC-130s, these aircraft don’t have the advanced ESM and self-defense suites that the RB-8 inherently does, making them more vulnerable to hostile forces, even far from the front lines. With the P-8 already getting towed electronic warfare-enabled decoys, its ability to survive even an unforeseen and more advanced threat will dramatically increase.

In addition to its wing stations, inside the P-8’s weapons bay, there are five hardpoints, each capable of carrying 1,000 pounds. Mk 54 torpedoes, which weigh about 500 pounds each, are the baseline weapon of choice for the P-8 weapons bay, along with Quickstrike mines. It would seem that this same bay could hold between 10 and 20 GBU-53/B StormBreakers, previously known as Small Diameter Bomb IIs (SDB II). The precision-guided munitions can hit moving targets in any conditions at over 40 miles from their launch points, which gives them a brutal anti-ship capability, especially against swarms of small boats in the littorals.

Alternatively, 500-pound or 1,000-pound JDAMs or laser-guided bombs, or even five small cruise missiles capable of standoff attacks, such as Israel’s Delilah or the new Sea Breaker anti-ship missile, could be carried internally. Israel is already intending on selling Sea Breaker to the United States. Finally, advanced air-launched decoys, like Miniature Air-Launched Decoy X (MALD-X), could be launched from the weapons bay.

Outfitted with a fighter’s modular AESA radar, the RB-8 could also potentially carry air-to-air missiles, providing for its own contingency defensive air capability. In fact, this aircraft, with its inherent networking capability, could also carry outsized very long-range air-to-air missiles, or air-to-air missile delivery systems, on its external pylons, as well, acting as a remote arsenal ship for fighters deployed far downrange.

Swarm Mothership

Things get even more interesting when we look at the infrastructure left over from the RB-8’s maritime patrol predecessor. The P-8 can carry 129 A-sized sonobuoys. The aircraft has three L3 Harris Sonobuoy Launching Systems, which are automated rotary launchers that can fire 10 sonobuoys in rapid succession before reloading, which happens inside the cabin. The P-8 also has individual manual sonobuoy launchers. While sonobuoys really don’t apply to our notional RB-8, although they could assist in seeding sonobuoy screens alongside their P-8 cousins, small drones can be deployed within the form factor of these A-sized sonobuoy tubes. Packing UAVs into this size sonobuoy tube was an initiative dating back to 2004. Fast forward to today and there are remarkably advanced off-the-shelf drone options.

For instance, the ALTIUS-500 was built to be launched from an A-sized sonobuoy launcher-equipped platform at altitude. The ALTIUS-500 has a range of over 150 miles and can be configured for a number of roles, although today it is made to act as a magnetic anomaly detector drone for submarine hunting. Just using what is leftover from the P-8, 30 of these, or a similar drone type that can fit into the A sonobuoy’s form factor, such as Raytheon’s Coyote, could be launched in rapid succession. Three additional reloads of 30 drones could be carried and quickly deployed in successive waves. We are talking about an amazing ability to rapidly deploy an overwhelming standoff swarming capability—one that could include any mix of surveillance, electronic warfare, decoy, and kinetic types in a single swarm.

The A-size sonobuoy launchers already included in the stock P-8 even have the ability to deploy stacks of 32 tiny CICADA drones in one shot. The point being, the existing launchers can be used to turn the P-8 into a seamless swarm delivery system/mothership and it also has space and communications to control those swarms once launched.

But things get even more interesting when you add apertures in the P-8’s fuselage to support Common Launch Tube (CLT) weapons and pressurized launchers—like those found on the KC-130 Harvest Hawk. This opens up a huge array of possibilities for more advanced internally launched weapons and drones.

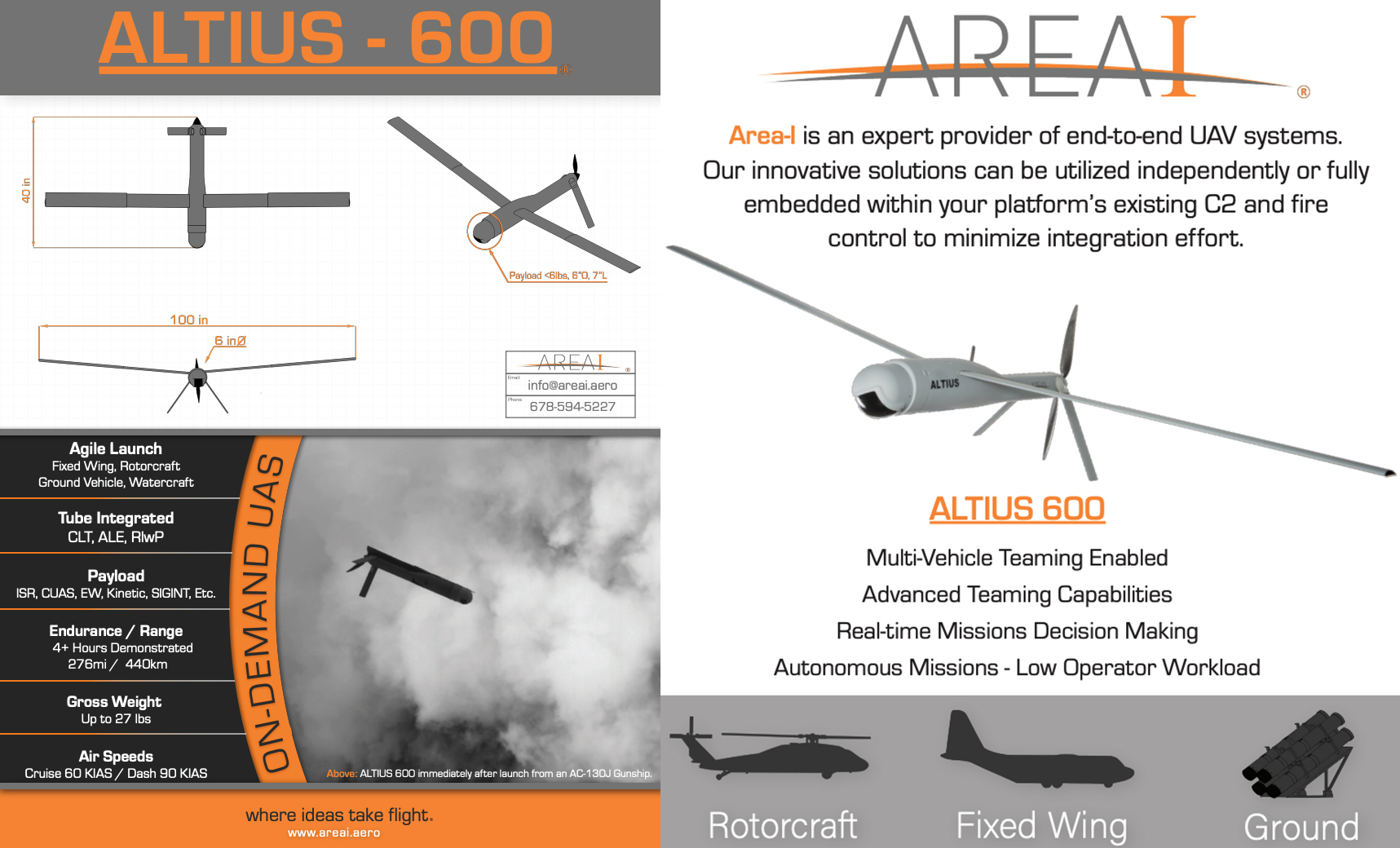

The ALTIUS-600 is becoming more and more popular as the go-to air-launched drone because it has been thoroughly tested and is extremely adaptable. Each weighs 27 pounds and can carry a seven-pound payload. This can include electronic warfare systems, signals intelligence and reconnaissance payloads, and a potent shaped-charge warhead. They are also capable of working cooperatively together in a swarm. Most importantly, the ALTIUS-600 has a range of roughly 275 miles, giving it true long-range standoff capability.

Because a good portion of the notional RB-8’s cabin will be unused, packing it with tube racks for various CLT-compatible weapons turns it into an even more potent arsenal ship. A swarm of a couple of dozen ALTIUS-600 drones loaded with EW, intelligence, networking relay, and explosive payloads coming at an enemy low over the horizon from hundreds of miles away, and launching them from a distance thousands of miles from a tanker, while providing on-station command, control, and monitoring of the swarm, is one brutally powerful capability.

Being able to deliver multiple types of swarms and standoff weapons, and layering those into a target area, including against a naval flotilla or a set of well-defended shore targets, would pose a huge challenge to an enemy. The drones could provide stand-in jamming support, decoy, and suppression of enemy air defenses to ensure an incoming cruise missile strike, even one also launched by RB-8, is successful, for instance. In fact, the RB-8 could assist other aircraft with their own strikes, layering in swarms of jet-powered and lower-end decoys in order to make sure a large strike package of other aircraft is able to hit their own targets. Likewise, a single RB-8 could launch a devastating attack on a surface action group, using a mix of swarms, air-launched decoys, and cruise missiles from standoff ranges. And all that can be launched by a single aircraft with minimal modifications.

Close Air Support Arsenal Ship

What’s so exceptional about the RB-8 concept is that it wouldn’t just be a standoff weapons truck intended for a peer-state conflict. Its long endurance, 737-like economy, defensive suite, large electricity-generating capability, and wide array of payload options would allow it to be an outstanding close-air support and armed overwatch asset in more permissive airspace. It could stay on station for up to 10 hours without needing aerial refueling support. That is a far cry from fighters that can require refueling as constant as nearly every hour. Its powerful FLIR could help with identifying targets down below and additional electro-optical/IR targeting capabilities could be added by bolting targeting pods or other sensor payloads onto one of its wing stations or fuselage attachment points. Best of all, a standard crew of as many as five could work very complex CAS situations simultaneously.

In addition, 2,000-pound class bombs could be carried on its wing pylons, although those shouldn’t be required on the majority of close air support missions. Its weapons bay could be packed with five JDAMs or laser-guided bombs, or at least double that in Small Diameter Bombs, while internally, a deep arsenal of Viper Strike, Griffin, and other Common Launch Tube-capable precision-guided weapons can be employed as needed, similar to how AC-130s and Harvest Hawks operate, but at jet speeds and altitudes. Even better would be the addition of a small guided direct attack munition that could fit within the confines of an A-type sonobuoy tube.

Drones can also be launched to provide additional eyes overhead areas that are outside of the RB-8 direct line-of-sight, but not beyond the reach of its Small Diameter Bombs, small cruise missiles, or its warhead-armed drones. With SDB alone, in many cases, it could theoretically provide close air support to multiple areas within about a 40-mile radius without turning to more advanced powered standoff weapons. Using its drones as reconnaissance platforms and munitions, that engagement range could be extended to over 250 miles. RB-8 launched drones could also be used to provide additional electronic surveillance or electronic warfare capabilities, work as communications relay platforms over mountainous terrain, or be used as loitering munitions. They could even possibly be used to intercept other hostile drones.

Electronic Missions With Ease

Bolting on a readily available system like the Intrepid Tiger II pod could also provide multi-role electronic warfare and communications intelligence support. Likewise, carrying the ASQ-236 Dragon’s Eye radar pod could enhance the RB-8’s ability to engage targets in any weather conditions and track enemy movements on the ground, finding enemy vehicles to stick its StormBreakers on. Self-protection jamming pods and towed decoys, paired with the RB-8’s high-situational awareness, could allow it to execute these missions even along the fringes of higher-threat environments.

Once again, it can do this at jet speeds. As such, it can respond to areas of need faster than its turboprop-powered counterparts.

Basically, if CAS is largely platform-agnostic as USAF’s leadership have repeatedly claimed, ok, then you don’t need a B-1B for it or an F-16. An RB-8 would be far more flexible, effective, persistent, and economical, and could provide for a far more independent concept of operations.

The RB-8 would be easily adaptable for other, non-kinetic roles. The airframe has already proven its ability to carry massively outsized radars and communications antenna farm pods using its under-fuselage attachment points. So, for the RB-8, anything you can strap on the wing or belly could potentially be employed. This could include powerful standoff jamming systems and even things like directed energy weapons that may be too cumbersome for a fighter aircraft to easily carry or too hard to integrate into a stealth bomber.

A critical communications gateway system is another possibility, a capability that will become increasingly important as time goes and that can take advantage of the aircraft’s existing communications suite. It’s also worth noting that the P-8 produces a lot of electrical power—it has extra generators that a standard 737 does not have—which would help when it comes to accommodating these types of power-hungry systems.

Boeing is also actively developing an open-architecture and modular pod system for mounting on the P-8’s fuselage. This system, known as the Multi-Mission Pod (MPP), will make integrating new outsized payloads onto the P-8, or a notional RB-8, simpler, as it will work directly with the aircraft’s open-architecture mission system. Furthermore, Boeing tells us its form factor “has been very carefully engineered to add capability and versatility while maintaining P-8’s ability to fly anywhere between 41,000 and 200 feet, fast or slow, near or far as the target and mission demands. It will not impact P-8’s flight profile.” As such, if you can fit it into the general form factor of the pod and it meets other basic requirements, it can be flown on the airframe without impacting its flight envelope. This will greatly streamline flight testing of new payloads, as well.

There is also the issue of unmanned aircraft control, not just for small drones, but also for loyal wingmen and even more advanced unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs). The RB-8 could operate as a forward control center for these largely autonomous systems. This concept of operations is especially relevant for loyal wingmen-like drones that will act as high-value asset protectors, an idea that is quickly gaining traction.

For instance, the Royal Australian Air Force’s Air Teaming System (ATS) will likely be monitored and directed from tanker and/or airborne early warning aircraft, as well as fighters. Similar concepts are being pushed and even tested in the United States. The RB-8, with its open-architecture interface, would be ideal for this role and the drones’ presence would give the plane a huge boost in survivability for operations in contested environments. Basically, it could provide an organic and highly dynamic self-escort capability. The RB-8 could also employ the advanced drones in offensive roles, as well.

Finally, the notional RB-8 could even fulfill light transport and on-demand logistics duties for small cargoes in a pinch.

Simply put, the future growth and adaptability potential of an RB-8 would be unlike any other combat aircraft out there. Just how fast new or even existing capabilities could be added to it is a major sell in itself.

An Extreme Value Proposition

Rewinding a bit, it must be made clear that above all else, the RB-8 could provide an economical, very low-risk path to extra long-range strike capacity in the near term. This is in addition to the secondary electronic intelligence collection mission that is already endemic to the over-tasked P-8 community. Currently, the need for the long-range strike mission set outstrips the capacity at hand, and despite the Air Force’s current plans, this situation could get worse long before it gets better. Procuring RB-8 aircraft would certainly offer some breathing room until the B-21 fully comes online and the tired B-1Bs can be finally pulled from service. After that, they can continue to augment the bomber force, while also addressing many additional mission sets that would be a poor, even fiscally irresponsible use of B-21 flight hours, or even those of an upgraded B-52.

Procuring the RB-8 would also help offset some of the risks posed by the USAF’s aging aircraft fleet. While the B-52 is a marvelous warfighting machine, it continues to age. What the next few decades of service will look like for the bomber as it approaches its 100th birthday can only be predicted. The RB-8 fleet would help hedge against any unforeseen issues with the type, and with the ultra-high-tech B-21, for that matter.

As far as actually seeing an RB-8 come to fruition, the problem is when you talk about buying something, no matter how ‘off-the-shelf’ it is, many will see it as a threat to other existing “sacred cow” programs. While it is important that the USAF buys enough B-21s, and 149 may be needed, anything with a major price tag that can help out with a portion of its mission set is viewed as some existential impediment to reaching that production number goal. There may be some truth to this, but at the same time, it is a poor way of looking at force structure, one that has done far more harm than good in recent decades.

The fact of the matter is 149 B-21s and 75 upgraded B-52s won’t be enough in terms of long-range weapons delivery platforms. The RB-8 can help pick up the slack at a very low comparative cost. And really, if it is going to suck funding from other sources, it should be spread more evenly based on all the missions it can do—from alleviating pressure on the concerningly geriatric manned electronic intelligence gathering fleet to doing the same for the fighter community in terms of close air support. This holistic point of view will not place its required funding all at the expense of one program or another.

By producing say 75 RB-8, at the cost of 15 B-21s (the latter of which will cost very optimistically around $650 million per copy), this could go a long way in providing more standoff strike capacity, and more flexible capacity at that, without digging deeply into the B-21’s production numbers. You could say the same thing for F-35A. Would you rather have another 110 F-35As or 75 EB-8s? In the big scheme of things, I think with the multitude of long-range, high-endurance missions it could accomplish, and the huge array of weapons it could carry, it would be hard to argue for the relatively short-ranged F-35As considering many hundreds are already in the inventory.

So, maybe cut it in half, the tactical and strategic side of the equation both gives up something, like seven B-21s and 58 F-35s. And what about the strategic intelligence gathering community? Maybe they could pitch in a bit as well. Their fleet of aging RC-135-based airframes could surely use some augmentation, at least as an interim measure. There is also the possibility of working with the Navy to make this a joint program.

Once again, these are just some examples of how we can view the RB-8 program if we have to look at every procurement opportunity as robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Finally, there is the issue of readiness. Neither F-35 nor B-21 will be ready to fly missions day in and day out like RB-8 would, or with such a low cost and logistical footprint. So while 75 airframes may not be a huge number, you would be squeezing many more completed sorties out of those airframes and at a much lower comparative price, in a given period of time. In addition, the P-8 shares vast commonality with the next-gen 737 airliner it was derived from. As such, sustaining it anywhere in the world, and especially during the duration of a conflict, will be a far easier proposition than a cutting-edge stealth bomber or fighter, or a 70-year-old B-52.

With that in mind, the RB-8 could also provide a lot of forward presence at a relatively low cost and with a relatively small footprint. Its inherent flexibility, long loiter time, and endurance capabilities, as well as its ease of support, means RB-8s can be forward deployed anywhere in the world and they can provide the widest mission set in the entire force while there.

What we are looking at here is an F-15EX-like solution to a different problem, albeit under similar circumstances. Just the fact that the F-15EX made it to fruition at all is evidence that an RB-8 concept may have legs. F-15EX was all about bringing in a low-risk, mature capability set as soon as possible while also providing an airframe that has a very long service life, proven availability and efficiency, and one that can do a wide array of missions its higher-end counterparts are ill-equipped to do, or doing so would be a waste of their precious airframe life. It was also an aircraft with the vast majority of its development already paid for, just like the RB-8 concept.

It may not be sexy, but the RB-8 is an incredible opportunity sitting on a plate before the Air Force and even possibly the Navy. It’s a comparatively low-cost weapon system that can check so many boxes in any future fight the U.S. may find itself in. Luckily, the P-8 order book has remained strong for the time being, and an additional bulk order could potentially allow for a very attractive unit cost.

The P-8 is built on its own dedicated line in Renton, Washington. Boeing tells us this allows it to more easily scale up production if need be. Producing a couple of planes a month is not an issue now and that can be increased as needed. But once that line is shuttered, the 737 Max would have to be adapted for the role, which would take a lot of time and cost a lot of money to integrate and validates the original P-8’s capability set onto. This will likely make the entire concept unviable. So, this isn’t a wait for eternity proposition. There could be additional orders for a P-8 derivative, possibly from the Army, in the not-so-distant future, as well. This would only add to the supportability of the type and the potential for a big block buy at a very attractive price.

The RB-8 concept should at least be carefully and thoughtfully evaluated. In fact, in an age where those in command often talk about how many air combat capabilities are increasingly platformed agnostic, the bizarre reality that an off-the-shelf, fully militarized 737 isn’t a compelling solution to a wide array of glaring challenges is quite puzzling.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com