Over the weekend, North Korean state media released a series of pictures of ballistic missile launches the country had carried out between September 25 and October 9, including from the rare and extremely provocative shot over Japan last week. In doing so, officials in Pyongyang revealed a previously unknown capability in the country’s missile arsenal, the ability to fire ballistic missiles intended to be launched from submarines from submerged launchers in lakes. While North Korea has mobile ballistic missile launchers, some of them gigantic in size, and has previously demonstrated the ability to employ ballistic missiles from trains, all of which enhance survivability, a lake-based launch concept could offer another level of protection. This is especially true when it comes to realizing some kind of rudimentary second-strike nuclear deterrent.

An official news story from the Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) accompanying the pictures said that the launch of the missile from the lake – technically a reservoir – was conducted on September 25. The exact type of missile does not appear to have been named in the news item, but pictures clearly show that it is an example of an apparently short-range submarine-launch ballistic missile (SLBM) type that the North Koreans first unveiled publicly in October 2021.

“At dawn [on] September 25, a simulated launching drill of [a] ballistic missile loaded with [a] tactical nuclear warhead was conducted at the underwater launching ground in a reservoir in the northwestern part of Korea,” KCNA said. “The drill was aimed at confirming the swift and safe operational order during the taking out, carrying and use of tactical nuclear warhead, inspecting the reliability of the universal operation system and mastering the system practicing the ballistic missile launching ability at the underwater launching grounds and inspecting the rapid response posture.”

“The fired tactical ballistic missile flew to the air over the fixed target in the East Sea of Korea along the set track and the reliability of warhead detonating in the fixed height was confirmed,” the story added. “The orientation of planned construction of underwater launching ground in the reservoir was also confirmed through the practical drill.”

Two details from the KCNA story are immediately notable, the first being the official statement that this missile is at least designed to carry a “tactical” nuclear warhead. The dimensions of the missile would indicate that any such nuclear warhead would have to be relatively small, adding to previously available evidence of North Korea’s ability to produce warheads of this general size.

In addition, the language KCNA used to describe this launch indicates that this lake bottom launch system is at least designed to be an operational weapon system, rather than some kind of test fixture. The way the official news story talked about the other launches similarly pointed to exercises meant to demonstrate operational capabilities, or intended operational capabilities, rather than developmental tests of the weapons themselves.

All of this is well in line with statements from North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and other officials in the country, who have repeatedly made clear that they have no intention of giving up their nuclear arsenal and are looking to be treated like any other nuclear power. Talks between the North Koreans and the United States, as well as with the South Koreans, on nuclear, as well as missile-related issues, among others, have been stalled for some time now. They look unlikely to resume any time soon in light of the recent launches.

In the context of a traditional deterrence policy, a lake bottom nuclear ballistic missile launch capability does definitely make a certain amount of sense. North Korea has demonstrated its ability to produce underwater ballistic missile launch systems for test purposes and it would not be hard to see how those designs could be leveraged to create an operational launch system. Whether the launcher is physically moored to the lakebed or uses some other kind of anchor to keep it from drifting is unclear.

Those underwater launchers could be very difficult to spot depending on the exact depth of the lake or reservoir, as well as the composition of the water. While there are only a limited number of large lakes that would be most suitable for deploying these systems in North Korea, an opponent would still likely have to devote significant resources to determine which ones contained missiles and where exactly those missiles might be emplaced within any particular body of water. Depending on the circumstances, this may be impossible to do reliably in a remote fashion.

If the launch systems are mobile to any degree, North Korean forces might be able to move them at irregular intervals. Empty launchers or other decoys could further complicate the targeting process, once again, that is if they can be detected reliably at all. Together with the difficulties involved in locating the underwater launchers, or potential launchers, in the first place, this could create a so-called ‘shell-game’ dilemma for enemy forces trying to figure out where to strike to neutralize them.

As such, even with significant intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, an opponent would likely feel compelled to strike all potential target locations to ensure the complete destruction of the missiles. Depending on the depths of the launchers, specialized munitions could be required to attempt that. The other option is a set of nuclear strikes, which could immediately turn a still-conventional conflict into a nuclear one.

Altogether, the ability to fire missiles from the bottom of lakes would seem to be, at least in part, a very practical effort on North Korea’s part to develop something akin to a second-strike deterrent using the resources available. This also offers a useful way to employ their SLBM designs without the need for submarines.

The North Koreans have had significant success in developing solid-fuel ballistic missile designs that could be fired from a submarine, but have faced many more difficulties in actually acquiring suitable boats. The North Korean Navy’s existing fleet of submarines capable of launching ballistic missiles is both extremely small and composed entirely of dated diesel-electric designs that are likely relatively loud and would be very vulnerable to detection prior to launch.

North Korea’s previously demonstrated rail-based ballistic missile capability, seen in the video below, would also appear to be intended, at least in part, to provide an additional more survivable launch option, as do their mobile launchers, which can come in enormous sizes. A potential lakebed missile farm takes survivability a significant step forward and could really complicate a conventional war plan for the U.S. military and its South Korean partners.

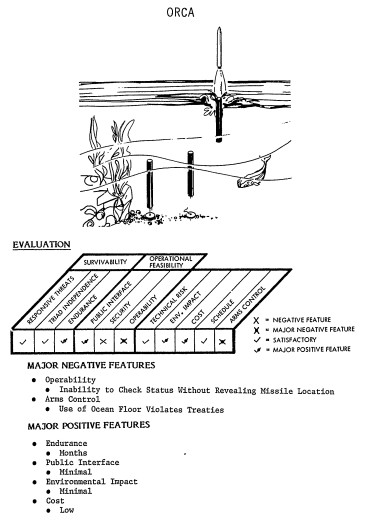

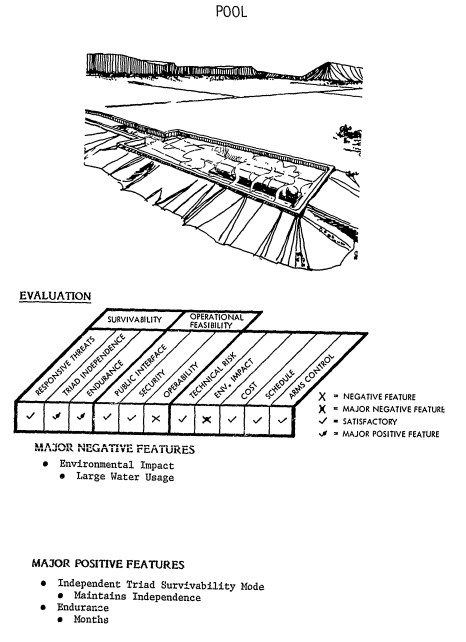

North Korea is not the first to have considered doing something like this for exactly these reasons, either. In the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. military actively considered off-shore seabed launchers and launch systems submerged in man-made pools filled with opaque water among many options for how to reduce the vulnerability of deployed MX intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM). The MX missiles, which were subsequently designated LGM-118A Peacekeepers, were ultimately loaded into traditional silos before their retirement in 2005. LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBMs, which were in service before the LGM-118A and are currently the only operational U.S. ICBMs, are also loaded into silos.

Much more recently, the U.S. Air Force looked into the idea of firing ICBMs from the bottom of lakes, among other things, as it developed a basing plan for its future LGM-35A Sentinel ICBMs. However, the service has decided that these missiles, which are set to replace the current arsenal of Minuteman IIIs, will also go into silos, as you can read more about here. Of course, the U.S. has a very robust second-strike deterrent in the form of its nuclear ballistic missile ‘boomer’ fleet of submarines and the ground-based ICBMs aren’t really meant to be survivable. Instead, they are meant to complicate an enemy’s ability to execute a surprise first strike and to suck up the enemy’s warheads. Hence why it is referred to it as the ‘nuclear sponge.’

Last year, it also emerged that the Chinese military is constructing a number of large silo fields for ICBMs. While the silos themselves appear to be relatively traditional in design, they are positioned much closer to each other than one might expect to see. This has raised questions about whether or not some of them might be left empty to create a shell-game problem for enemy targeters.

There are of course potential pitfalls and limitations to the lake-based missile launching concept, including the fact it could be difficult to perform general maintenance or otherwise inspect the missiles in their underwater launchers without giving away their locations. Still, this would not give away the entire missile field’s coordinates and if they were movable, this wouldn’t matter much at all. Having to do this work underwater is just that much more complicated, too. There are also environmental and security issues with such a concept.

As with North Korea’s rail-based ballistic missile capability, it does remain to be seen just how extensively the country might deploy lake-based launch systems, and whether any such details, claimed or otherwise, are made public. Certainly, there are major challenges with such a plan, as well. What is clear is that the regime in Pyongyang remains very interested in diversifying the country’s nuclear capabilities in ways that very much align with established views on nuclear deterrence. And maybe most importantly, the fact that they are pursuing this concept provides yet another tell that their submarine technology simply does not meet their second strike ambitions.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com