U.S. surveillance drones based on a popular civilian powered glider design could be headed to the Indo-Pacific region in support of Marine special operators. The War Zone was the first to report in-depth on these uncrewed aircraft, which are designed to be extremely quiet and operate discreetly thanks to their innocuous outward appearance, and have been flying in the Middle East for years.

A recent U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) contracting notice has provided additional details about what has been referred to simply as the Long Endurance Aircraft (LEA) in the past and is now designated as the RQ-29. It also offers a new window into current and future operational plans for the drones, which are U.S. government-owned, but contractor-operated.

“MARSOC [U.S. Marine Forces Special Operations Command] operates the RQ-29 unmanned aerial system (UAS), a USSOCOM unique configuration UAS, to support Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) for USSOCOM operations,” according to the request for information notice, which was first posted online on August 8. “RQ-29 aircraft are equipped with Electro-Optical/Infrared, ISR sensors, signals intelligence payloads, and VORTEX video and data transceivers, and are deployed at remote locations Outside the Continental United States (OCONUS).”

“This requirement is for the procurement of aircrews and contractor logistics services on the RQ-29 system. A fully operational system consists of the RQ-29 air vehicle, USSOCOM unique payloads and mission systems, Ground Support Equipment (GSE), and Ground Control Stations (GCS),” the contracting notice adds. “The fully operational system will be split into two elements: a Mission Control Element (MCE) to execute the mission, and a Launch and Recovery Element (LRE) to launch, recover, and maintain the air vehicle. RQ-29 aircraft are based on Pipistrel Sinus light sport aircraft that are converted to UAS.”

The RQ-29 has a cruising speed of 100 knots and an operating ceiling of 17,000 feet, according to Technology Service Corporation (TSC), the company behind the drone. It has a maximum endurance of around 40 hours, but this is closer to 24 hours with a “full Mission Payload Suite,” TSC’s website says. The converted Sinus is also “capable of Line of Sight (LOS) and Beyond Line of Sight (BLOS) operation through semi-autonomous functionality and ‘point and click’ operation.”

The recent contracting notice lists two potential operating locations in the United States, the U.S. Army’s Fort Huachuca in Arizona and Fort Liberty (previously called Fort Bragg) in North Carolina. There are also two anticipated OCONUS sites, one each in the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) and U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) areas of responsibility. Fort Huachuca is a major aerial ISR and drone training and test and evaluation base. Fort Liberty, which the contracting notice says could be the site of a “Mission Control Element,” is a hub for special operations and Army airborne units.

The two possible OCONUS sites are described as where “Launch and Recovery Elements” would be deployed, with the INDOPACOM site being further described as an “option.” Altogether, this is indicative of so-called “remote-split” operations where personnel at forward locations would help get the RQ-29s into the air and back down after sorties, while the actual missions would be ‘flown’ by individuals back in the United States.

The RQ-29 is capable of “fully automated takeoff to landing flight operations using hardened GPS navigation and an encrypted satellite-based command and data relay for true global operational access,” according to TSC, but a team would still be needed on the ground at any forward operating location to do maintenance and otherwise sustain the drones.

“Automation greatly reduces operator training requirements to less than 6 weeks,” the company data sheet adds. “Small ops crew size significantly lowers operating costs relative to other unmanned ISR platforms.”

The secretive Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), or other U.S. government entities working in cooperation with it, are known to have operated LEA drones in the past from Erbil International Airport in Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdish region. It is possible that the “potential” CENTCOM operating location mentioned in the recent contracting notice would just be continued RQ-29 operations from Erbil. The drones could also fly from a host of other locations in the Middle East, including a constellation of other air bases in multiple countries across the region that already host U.S. forces.

Regardless, the RQ-29 presents an ideal platform for conducting discreet persistent ISR missions in permissive airspace in support of the kinds of counter-terrorism and other low-intensity operations that continue to dominate the U.S. military’s activities in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere in the Middle East. Less likely to draw unwanted attention even if detected than a more traditional-looking drone like an MQ-9 Reaper, the LEA offers particular benefits for keeping tabs on specific individuals or small groups helping to establish their so-called “patterns of life.”

In a potential future deployment to the Indo-Pacific, RQ-29s could be used for a similar slate of missions to the ones they have likely been tasked with in the Middle East. For instance, since 2017, U.S. special operations forces have been providing various types of support to the armed forces of the Philippines in their fight against the ISIS franchise in that country and other terrorist groups as part of Operation Pacific Eagle-Philippines. The mission, which followed on from years of previous U.S. counter-terrorism operations in the country during the Global War on Terror era, has included conducting aerial ISR using drones.

In the Pacific, RQ-29s could be useful for discreetly and persistently monitoring other kinds of malign activity, especially in contexts short of actual conflict. This is something the U.S. military has previously outlined as an important routine task in the Pacific region.

As one example, for nearly a year now, there has been a particular surge in friction, including violent skirmishing, between China and the Philippines over control of the Scarborough Shoal, a grouping of islets and reefs that lie in the northeastern end of the South China Sea. The South China Sea as a whole is hotly contested, with the Chinese government having extensive territorial claims that virtually the entire international community rejects.

Amid this increasingly worrisome situation, at least one U.S. MQ-1C Gray Eagle operating from the Philippines, possibly belonging to the elite 160th Special Operation Aviation Regiment (SOAR), was been spotted flying in the vicinity of the Second Thomas Shoal back in May. Other U.S. Navy P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol planes have also been observed overhead.

U.S. crewed and uncrewed aerial ISR aircraft have also been charged with keeping an eye out for North Korean sanctions-busting activities at sea and illegal Chinese fishing operations across the Pacific. There is already a precedent of sorts within the U.S. government for using a platform akin to the RQ-29 to support missions like these. During the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. Coast Guard operating multiple types of very quiet, high-endurance power gliders, but with pilots in them, in support counter-drug operations in the Caribbean, as you can read more about here.

In conducting surveillance of Chinese activities, in particular, RQ-29s would not be limited to just monitoring concerning developments like those around the Second Thomas Shoal or otherwise providing additional situational awareness over potential flashpoint areas. The drone’s signals intelligence suite, in particular, could be used to glean valuable insights into Chinese tactics, techniques, and procedures through intercepted communications chatter.

RQ-29s could be employed in roles beyond ISR, too, including as flexible elevated communications relay nodes

It is possible that RQ-29 operations with their small logistics footprint and low cost could expand further within the Middle East and/or Pacific, and beyond, in the future. The recent contracting notice explicitly notes that “aircraft inventory requirements shall increase as procured aircraft are delivered,” pointing to a growing fleet of these drones.

It’s also worth noting here that there are a number of other ultra-quiet and long-endurance drone programs that we know about within the U.S. military today. This includes the Air Force’s Unmanned Long-endurance Tactical Reconnaissance Aircraft (ULTRA), which is based on a commercial sport glider, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) XRQ-73A Series Hybrid Electric Propulsion AiRcraft Demonstration (SHEPARD) drone, a stealthy flying wing design with a hybrid-electric propulsion system. The XRQ-73A follows directly from an earlier design called the XRQ-72A Great Horned Owl that the U.S. Intelligence Community developed in cooperation with the Air Force.

ULTRA drones were forward deployed at Al Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates at least as of earlier this year. A report from The High Side in July said that drones have conducted marathon sorties to surveil members of ISIS’ faction in Afghanistan, but were about to be sent back to the United States ostensibly due to their cost to operate, pegged at “less than $2 million per month.”

There is long-standing interest dating back to the 1960s in the U.S. military and U.S. Intelligence Community in very quiet and long-ranged crewed and uncrewed aircraft to conduct ISR and other missions with less of a chance of being detected or otherwise raising suspicions inside hostile territory, or otherwise denied or sensitive areas.

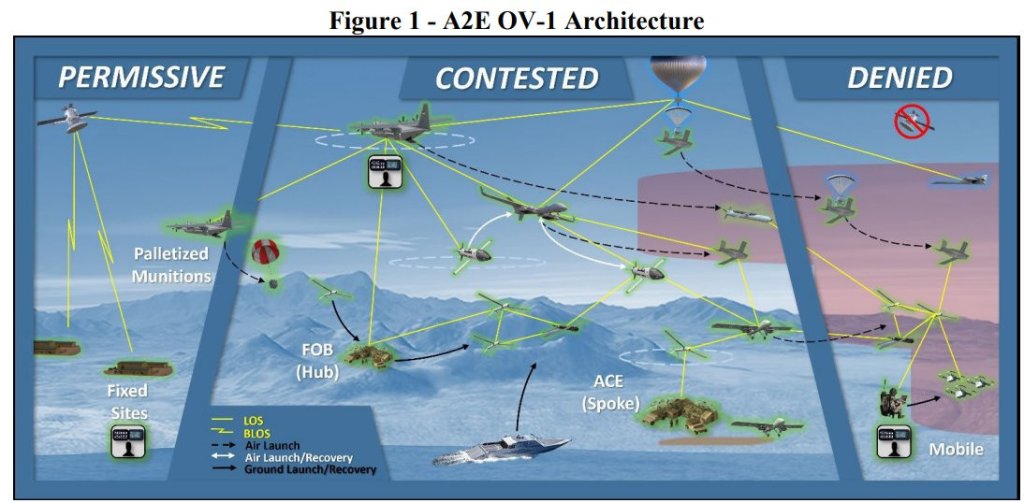

The RQ-29 is far from a deep-penetrating platform and the XRQ-73 looks to be well-positioned as an upper-tier companion to tackle higher-risk missions. A graphic offering a very broad depiction of the Air Force Special Operations Command’s (AFSOC) Adaptive Airborne Enterprise (A2E) operating concept that emerged earlier this year notably used the SHEPARD design as an example of something capable of operating in a denied environment.

All told, it is possible, if not probable that additional work is being done now on other similar efforts in the classified realm. The LEA Program that led to the RQ-29 itself lived in the black world for years before coming into the light.

In the meantime, SOCOM vision for the RQ-29 looks to be growing with an eye toward bringing the drones and the specialized capabilities they offer to the Pacific.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com