As Philippine security forces continue to fight the Maute group rebels, aligned with ISIS, for control of the city of Marawi in the southern part of the country, the United States is reportedly considering launching its own air strikes against the militants. This would represent a significant escalation in U.S. involvement in the emerging conflict and a shift in the policy of the President of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, who has been an outspoken critic of American military intervention in the past.

On Aug. 7, 2017, NBC News, citing two unnamed defense officials, said that the U.S. military was considering launching aerial attacks on the Maute fighters as early as the following week as part of what would be an official, named military operation. American forces have already been providing intelligence and other advisory support to their counterparts in and around Marawi at least since June 2017.

“We’re providing them some training and some guidance in terms of how to deal with an enemy that fights in ways that is not like most people have ever had to deal with,” Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who was in the country for a scheduled visit, said the same day at a press conference. “I see no conflict, no conflict at all in our helping them with that situation.”

Air strikes have already been a very visible component of the Philippines government operations in Marawi. However, as The War Zone has noted, the country’s Air Force has very limited capabilities when it comes to this kind of complex urban warfare, relying on a mix of aging OV-10M Bronco and SF.260 light attackers, newer FA-50PH light jet fighters, and light gunship helicopters.

The Philippines has been looking into buying fixed-wing gunships based on turboprop conversions of the venerable C-47 transport, as well as new A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft, but has yet to finalize any deals. The United States did recently help deliver a small number of Cessna C-208B Caravan aircraft with surveillance equipment, as well as unspecified small unmanned aircraft, according to Tillerson.

In the end, most, if not all of these aerial attacks have involved “dumb” munitions, which can be dangerous to friend and foe alike. There was a report of at least one potential friendly fire incident on May 31, 2017.

So, it’s not surprising that authorities in the Philippines may be interested in bringing in American air power. U.S. planes, either manned or unmanned, would expand the total number of aircraft available for air strikes, as well as add precision guided munitions to the equation for more accurate attacks.

The NBC News story did not say what aircraft the U.S. military was considering deploying, but the immediate assumption was that American commanders would employ either U.S. Air Force MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper or U.S. Army MQ-1C Gray Eagle drones, all of which are able to carry a variety of guided bombs and missiles. The U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command has already proven it can establish drone surveillance operations virtually anywhere in a matter of weeks.

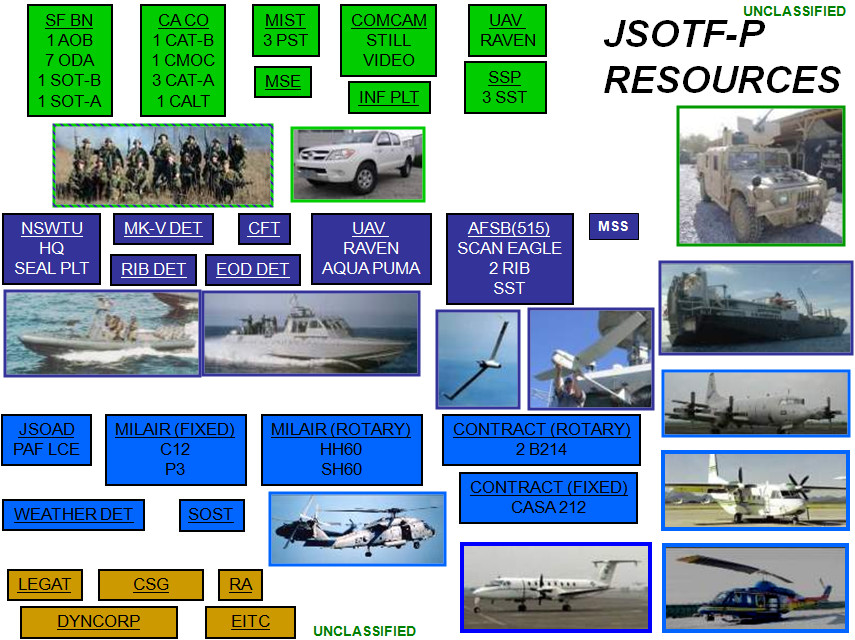

Setting up a mission can take even less time if there is an improved air base or airport that American crews can make use of instead of needing to build its own facilities. For more than a decade, a U.S. special operations task force, known as Joint Special Operations Task Force-Philippines (JSOTF-P), made use of a number of Philippine bases, including Edwin Andrews Air Base situated less than 200 miles southwest of Marawi, for aerial surveillance and other operations.

Another option would be sending manned aircraft of some description, including high performance multi-role combat aircraft. As part of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which the United States and the Philippines signed in 2014, the U.S. military expanded routine training exercises in the country proving it could deploy and operate small numbers of jet aircraft in cooperation with the Philippine Air Force.

In April 2016, the U.S. Air Force sent a contingent that included four A-10 Warthog ground attackers to the country to take part in a series of drills. Two months later, the U.S. Navy deployed four EA-18G Growler electronic warfare aircraft for their own rotation.

There is the slim possibility the United States could choose to arm aircraft it already has flying in the country, too. The Navy’s P-3C Orion patrol planes, spotted conducting surveillance over Marawi in June 2017, can carry AGM-65F Maverick missiles for use against surface targets.

During the U.S.-led intervention in Libya in 2011, a P-3 destroyed a patrol boat with one of these weapons. These missiles, with their very flat flight profile, would have limited utility against fighters hiding in Marawi’s more densely packed areas, but it could offer an immediate precision munitions capability. It would be an ideal choice for attacking insurgents riding around the city in vehicles.

But whatever aircraft and weapons the United States might employ, the decision would mark a significant escalation in American involvement in the fighting against ISIS branch in the Philippines. In 2015, the U.S. military formally ended operations focused on Al Qaeda-linked militants, which had started in 2002. The remaining American personnel from that mission were reassigned to a so-called “augmentation cell” within the Embassy tasked with continued, but limited advisory support for the Filipino armed forces.

“The … mission transitioned to rotational assignments of U.S. SOF [special operations forces] based on close consultation with our AFP [Armed Forces of the Philippines] partners to appropriately tailor our approach to their requests,” U.S. Army Major Kari McEwen, a spokesperson for Special Operations Command Pacific, told The War Zone in an Email on May 31, 2017. “The number of U.S. special operations forces in the Philippines fluctuates based on rotational Mutual Defense Board and Security Engagement Board (MDB-SEB) activities and requests from the Armed Forces of the Philippines.”

NBC News reported that the United States would likely justify any strikes under the principle of “collective self defense,” which essentially means that American advisers working with partners near active combat can call in fire support to defend themselves if they too come under attack. The U.S. military has previously cited this same broad precedent when explaining fire support missions in other shadowy conflict zones, such as Somalia. The plans for a more active American presence in the Philippines would also be in line with the increased willingness of President Donald Trump and his administration to use military force in higher risk situations, as we had already noted with regards to Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

However the U.S. government explains the situation, it would also represent a significant policy shift for authorities in the Philippines’ and President Rodrigo Duterte in particular. Duterete threatened to reduce or outright end various military cooperation agreements with the United States both during his campaign and after his election victory in 2016.

These comments had mainly been in response to criticism from the U.S. government over reported gross human rights abuses during his war on the drug trade as Mayor of Davao City, including the use of roving death squads that he apparently personally oversaw. As time went on his rhetoric only became more charged and he personally insulted then President Barack Obama as a “son of a whore.”

He was also an outspoken critic of previous U.S. military involvement in the country, including the reported use of drones against Abu Sayyaf terrorists and Moro rebels, which he suggested had impeded efforts to cut peace deals with these groups. For their part, the United States and the government in the Philippines have both repeatedly denied reports that unmanned aircraft ever carried out strikes in the country.

“I will not allow them to use our airport for them to launch their drones,” Duterte told a gathering of ethnic Moros on Aug. 12, 2013. “I do not want it. I do not want trouble and killings.”

Relations between Duterte and Trump, who observers have compared to each other in various ways, have been much warmer and may help explain the change of heart. According to a leaked transcript of a phone call between the two leaders in April 2017, Trump pointedly told Duterte he was “doing a great job” in his controversial fight against drug traffickers.

Still, Duterte’s rhetoric may make it difficult for him to admit he sought American help against the Maute group and their allies. In June 2017, he said he was unaware of any U.S. special operations forces in Marawi and had not asked for their support. On Aug. 8, 2017, the Philippines Department of National Defense (DND) said reports of impending U.S. air strikes were false.

“The DND denies any discussions regarding the use of US drones to strike against Daesh-inspired terrorist groups in the Philippines,” public affairs office chief Arsenio Andolong declared in the statement. “The AFP also states that no such discussions have occurred at their level.”

We’ll probably have to wait and see if American manned aircraft or drones suddenly appear over Marawi, just like the special operations forces quietly arrived on the scene with little fanfare.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com