Ukraine’s military intelligence service has released details of a new Russian cruise missile, the S8000 Banderol, that it claims makes extensive use of components sourced from foreign manufacturers, including in the United States. Unusually, the missile was apparently developed for launch from drones and has reportedly already been used in combat in the war in Ukraine.

The claims about the Banderol were made by the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s Main Directorate of Intelligence (GUR), which has also published photos of the weapon, which little was known about previously. A product of the Kronstadt company, which is best known for developing drones, the Banderol is said to be primarily intended for launch from the firm’s Orion uncrewed aerial vehicle, which is roughly similar in size to an MQ-1 Predator. At least one photo has appeared that purportedly shows a Banderol missile under the centerline of an Orion drone, apparently during testing in Russia. The Russian name Banderol approximately translates to package, or small parcel, in English.

Subsequently, the GUR says the missile will be adapted for launch from Mi-28N Havoc attack helicopters, a type that you can read more about here.

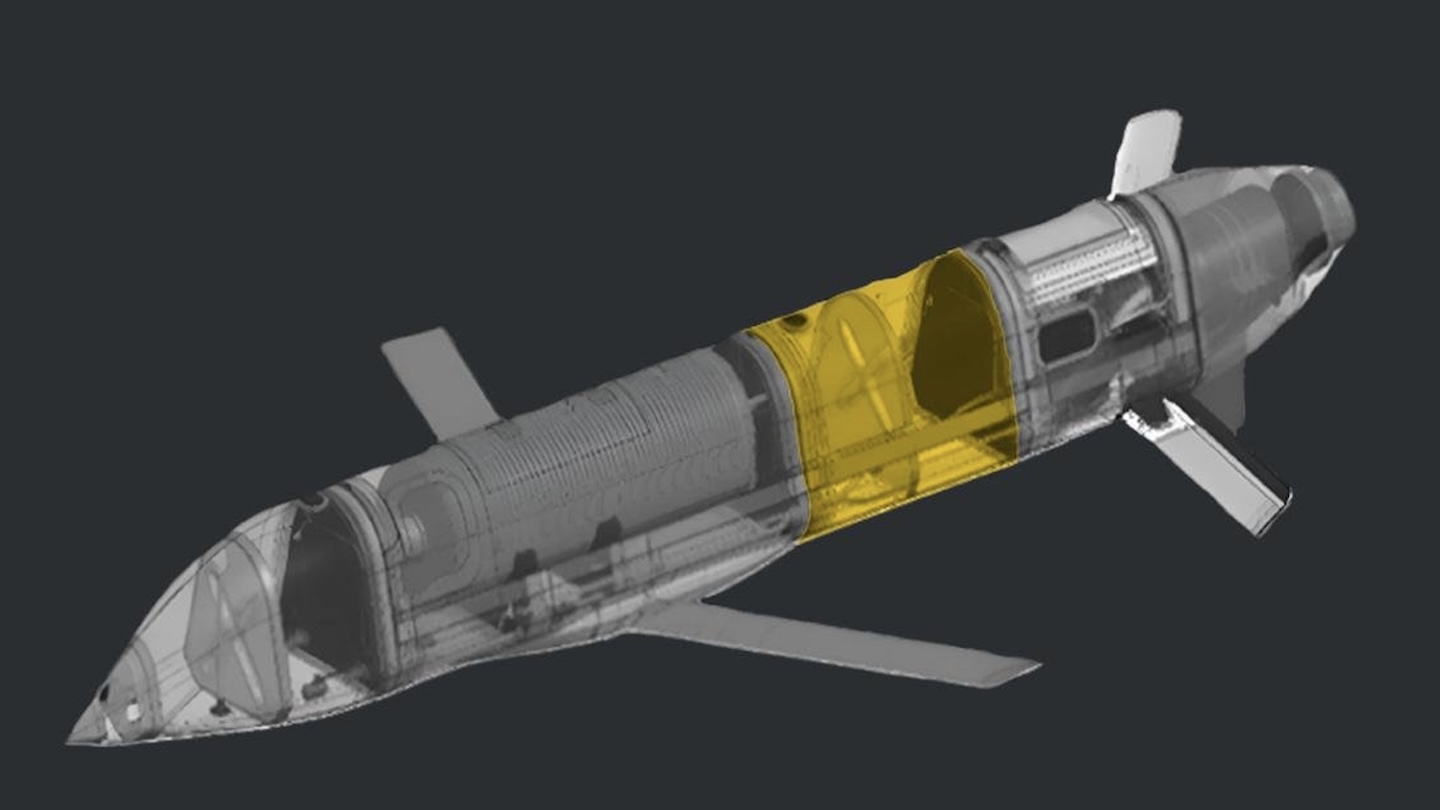

Powered by a small jet engine and fitted with pop-out wings, the Banderol has a range of 500 kilometers (311 miles) and a speed of 500 kilometers per hour (310 mph), according to the GUR. The warhead reportedly weighs 250 pounds. The GUR also claims that the Banderol is more agile than other Russian cruise missiles, suggesting that it may be intended to use flight profiles that are better able to evade Ukrainian air defense systems.

Although the GUR doesn’t mention details of operational use of the Banderol, the detailed technical study that the agency provides suggests that it had access to one or more relatively intact examples of the missile, recovered after they crashed or were brought down by air defenses on Ukrainian territory. Unconfirmed accounts suggest that the missile has been used to attack targets in southern Ukraine on multiple occasions.

The GUR’s analysis also provides a full rundown of what it says are foreign components used in the Banderol, part of an extensive effort that involves “around 30 companies” providing “more than 20 key components,” and potentially more that have not been identified.

The various non-Russian components are said to include the missile’s powerplant, an SW800Pro jet engine from the Chinese Swiwin company.

The GUR also identifies an RFD900x telemetry module (either sourced from Australia or a Chinese copy of the original), an inertial navigation system (“likely of Chinese origin”), rechargeable batteries from Murata (Japan), and Dynamixel MX-64AR servo drives from Robotis (South Korea).

There are also “almost two dozen microchips” in each missile, “from U.S., Chinese, Swiss, Japanese, and South Korean manufacturers,” the GUR adds. These are supposedly sourced mainly by the Chip and Dip network, one of Russia’s largest electronics distributors and a company that’s also under sanctions.

Other components of the Banderol are apparently from Russian production, including a Kometa digital antenna for satellite navigation, designed to reduce the ability of enemy jamming. This equipment is also used in Geran long-range one-way attack drones and in various glide bombs.

The use of foreign-sourced components in Russian-made weapons, especially drones and missiles, is by no means new.

Notably, the GUR previously claimed it found dozens of Western-made components in the Russian S-70 Okhotnik-B (Hunter-B) flying wing drone that was downed over Ukrainian territory last year, in an incident you can read about here.

Clearly, despite sanctions, components manufactured outside of Russia are being used in weapons employed in Ukraine. In particular, microelectronics and other high-tech components are found regularly in Russian defense products.

Russian weapons “depend on foreign components,” the GUR has stated on its database. “Without them, they cannot continue to fight, occupy, and kill.”

As of November last year, the GUR said it had found more than 4,000 foreign-made components in nearly 150 captured or recovered Russian weapons.

As we have explored in the past, components vital to Russia’s war in Ukraine don’t necessarily have to be sourced directly from the manufacturers. With a massive and largely unregulated market for recycled microelectronics, in particular, largely emanating from China, there are plenty of other options. Meanwhile, the SW800Pro jet engine that is said to power the Banderol is available to buy on the AliExpress website for around $16,000. It is mainly offered for aeromodellers.

In addition, many useful components can be found in innocuous appliances and other non-military items. These kinds of items are much harder to prevent from falling into the wrong hands, although U.S. officials have the authority to prevent shipments of dual-use items if they consider the application to have critical military uses.

Already, U.S. government agencies have issued sanctions against hundreds of companies around the world that provide Russia with technology, although obviously certain items are still making it through.

Russia “has decades of experience evading export controls and sanctions, building a system of transshipment routes, cultivating networks of diverters in third countries, and employing sophisticated deception tactics,” the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) noted last year. “Malign actors go to great lengths to circumvent government restrictions and established company compliance actions, evading even the most sophisticated screening and due diligence efforts.”

It’s worth noting, too, that Iranian and North Korean weapons used by Russia and recovered by Ukraine have also been found to contain large amounts of Western components.

While the use of foreign components in weapons used by Russia in Ukraine is not new, the use of the Banderol cruise missile appears to be a novel development.

We don’t know for sure, at this point, how the cruise missile was used, but the concept of a weapon of this type launched by a drone is an unusual one. While a relatively slow- and low-flying drone like the Orion would be a much more vulnerable launch platform than a fixed-wing tactical aircraft, the range of the Banderol would mean it could be launched a considerable distance from the target, including from across the border, in Russian airspace.

For many months now, Russia has been seeking to expand the number of weapons it has for standoff strikes on Ukrainian targets.

Mounting losses of Russian tactical aircraft to Ukrainian ground-based air defenses highlighted the need for weapons that can strike targets surgically at and well behind the front lines.

Most notoriously, Russia fielded the UMPK, a fairly crude type of guided glide bomb that has caused considerable difficulties for Ukrainian air defenses ever since its introduction around early 2023. The UMPK series was followed by the UMPB, a more refined winged precision-guided bomb.

However, these weapons are unpowered. The Banderol’s small turbojet engine elevates it to the cruise missile category, and its reported range of 500 kilometers is very significant, if true. The long range is achieved at the expense of warhead size, with the Kh-69 air-launched standoff missile carrying a penetration or a cluster warhead weighing up to 680 pounds — more than twice as heavy as that reportedly used in the Banderol.

The exact guidance method used in the Banderol is unknown, so it’s unclear if the weapon can be programmed with a target’s coordinates after the aircraft has taken off, which would be required for the most time-sensitive targets.

The fact that it features an inertial navigation system and a jamming system should provide the weapon with a significant degree of resistance to electronic warfare jamming of the kind that is now increasingly being employed by Ukraine. The addition of satellite navigation, to correct for drift, is also an important factor since an inertial navigation system has accuracy limitations that get more pronounced the longer the weapon travels.

Overall, while the Banderol might have limitations compared to higher-end cruise missiles used by Russia, it’s obviously a lower-cost solution. This is important bearing in mind the number of targets Russia is prosecuting and the fact that more expensive weapons are likely in short supply. This is not only due to the heavy campaigns of airstrikes, but also Russia’s limited ability to manufacture high-technology weapons — at least without access to Western components.

Meanwhile, if it’s the case that the Banderol is optimized for launch from non-traditional platforms, namely drones and attack helicopters, it means that Russia’s bomber fleets and fixed-wing tactical aircraft can concentrate on their primary roles and use their established weapons. Ultimately, however, the Banderol could also be adapted to launch from other aircraft, too. Especially considering its drone launch, the end result would appear to blur the boundaries between a cruise missile and air-launched effects, an idea that is also fast gaining traction in the United States.

Presuming that Banderol is now being used in the conflict, we likely won’t have to wait long to learn more about this intriguing weapon. For Ukraine, meanwhile, the apparent addition of this new and apparently relatively low-cost standoff weapon to the Russian arsenal will be another cause for concern for Ukraine.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com