Things can go very wrong very fast in helicopters and sometimes there just aren’t many options to safely mitigate the issue. This was especially true during the early days of the rotary-wing boom. In the face of growing concerns over helicopter-related fatalities and injuries, the U.S. Navy worked on a unique escape module system in the 1960s which was designed to save the lives of as many individuals as possible by literally severing the helicopter in half.

The short clip below, which depicts a test of the system conducted by the Navy in 1966, gives a good depiction of what the novel escape module system was all about. In broad strokes, the service created a system that split apart the fuselage of a helicopter while airborne. A separated section would serve as an emergency escape capsule, allowing personnel lucky enough to be in the module to parachute below to safety — at least that was the idea.

It should be noted that escape capsule systems on aircraft were all the rage during the late 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s within the U.S. aerospace defense sector. The U.S. Air Force’s swing-wing F-111 Aardvark strike jet, for example, received an escape module design that ejected the entire cockpit. The B-58 Hustler, XB-70 Valkyrie, and the B-1A Lancer are some other examples of aircraft the leveraged different escape capsule concepts.

By the early 1960s, the need for some kind of helicopter crew escape system was clear to the Navy. As part of an early 1961 study on the feasibility of such a feature, all data on Navy and Marine Corps helicopter accidents involving critical injuries or fatalities were collated across the period from 1952–1962. It was found that a majority of accident victims could have been saved had an in-flight escape system been installed onboard the helicopters.

It was not long after the 1961 study that the Navy began a program to demonstrate the fuselage escape capsule concept as applied to a wide range of helicopters. That program started in 1964 under the direction of the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR).

A nearly 16-minute video on the helicopter escape module, produced by the Navy, can be seen below, which details its developmental history.

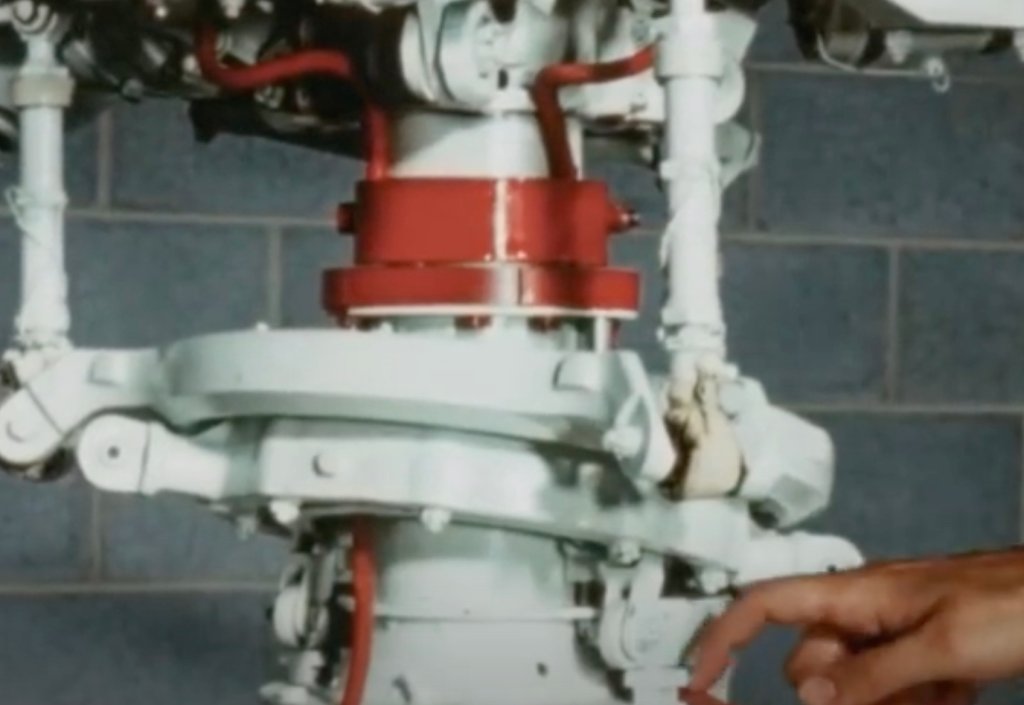

As the video above highlights, the Naval Weapons Laboratory in Dahlgren, Virginia, designed and developed a “ballistic system” for the separation and recovery of a helicopter escape capsule.

The system involved placing roughly 18 feet of continuous, aluminum-sheathed linear charge around the inside of the helicopter to sever the escape module from the rest of the fuselage. Two modified catapult rocket launchers, mounted aft on the port and starboard sides, were also used to ensure the escape module’s separation from the rest of the aircraft.

Detonating chord leads were used to sever the helicopter’s rotors and blast them out of the way, thus preventing them from interfering with the deployment of the capsule’s parachutes.

From 1964 to 1968, the Navy began testing the system on a number of helicopters, including Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knights, Bell UH-1E Hueys, and Piasecki UH-25B Retrievers.

Between March and June of 1966, alongside testing on the ground, five, full-scale tests of the system were conducted in the air using UH-25B testbeds. Three of the five tests were completed successfully at heights of 74, 143, and 187 feet. “In each case,” a subsequent report by the U.S. General Accounting Office noted, “the escape system functioned perfectly.”

“The fact that it worked at these altitudes is important because the earlier Navy-sponsored analysis revealed that 90 percent of the in-flight emergencies occurred at altitudes between 100 and 600 feet,” the report goes on to say.

On the basis of the successful tests, in June 1967 the Navy began to investigate the adaptability of the system to various helicopters. As part of its study, 14 helicopter types were considered, of which a total of four were deemed viable candidates to receive the in-flight escape system. However, none actually had modifications done for adding the escape module.

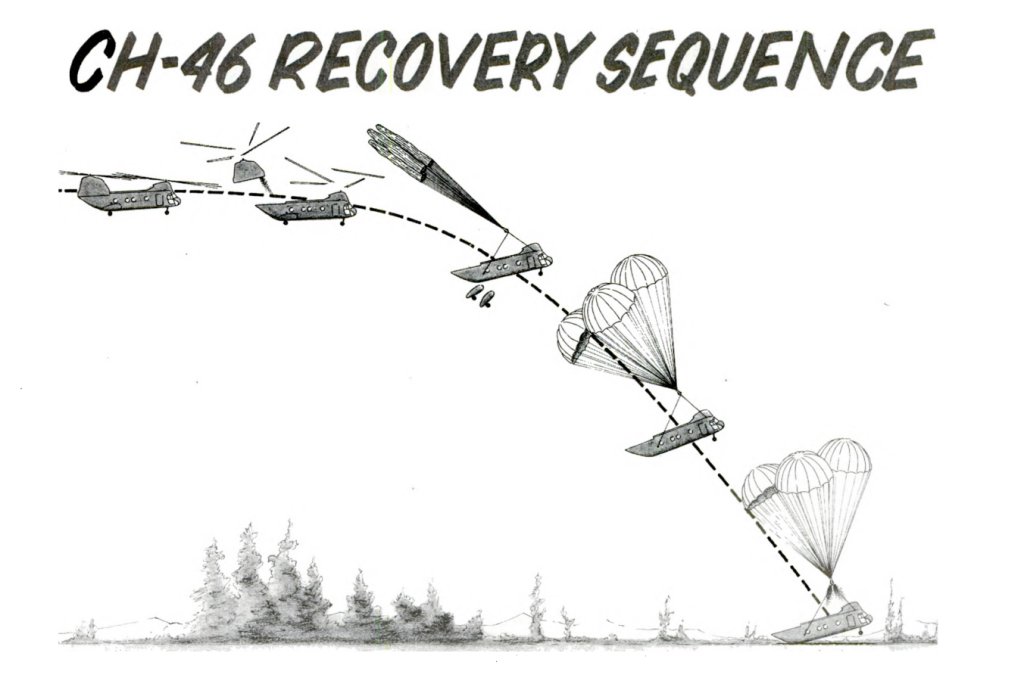

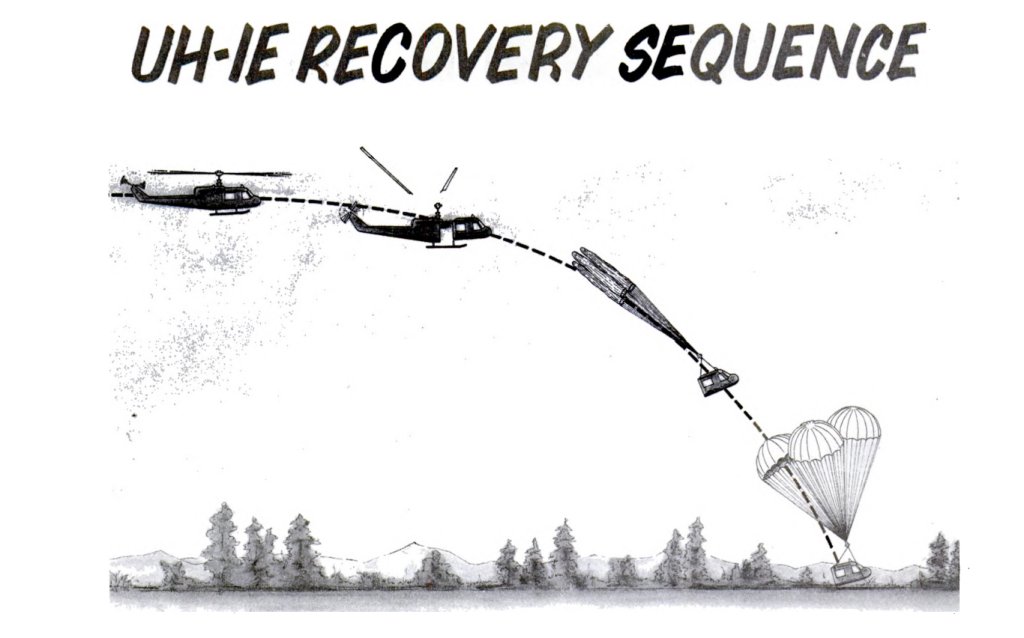

The Navy selected two helicopter variants in particular — the Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight and the UH-1E — for more detailed study, owing to the fact that many of them were in use at that time.

“The emergency in-flight escape system resulting from the study [for the CH-46] included a ballistic subsystem to sever the rotors and unoccupied parts of the helicopter and a recovery subsystem to lower the occupied part to the ground. Other survival features included a crash impact subsystem to protect against impact forces, an emergency flotation subsystem, and a passive defense subsystem,” the Navy noted.

While footage of Navy testing with CH-46s does not appear to exist, an illustration from the service’s subsequent research seen below shows the rear rotor nacelle and both rotors being blown completely off — allowing the entire airframe to be parachuted to the ground.

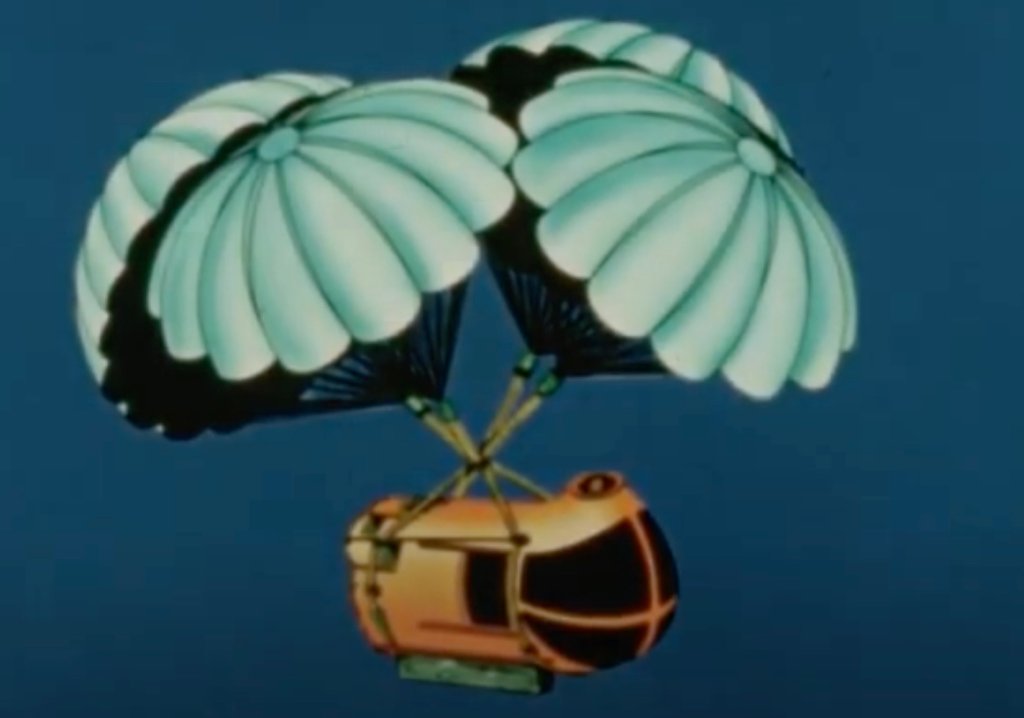

The recovery system for the UH-1E “consisted of four 36-foot, ballistically deployed parachutes to be used at altitudes above 100 feet and airspeeds from zero to 200 feet per second. Surface impact protection was provided by crash-energy-absorbing troop and crew seats, crash-resistant fuel cells, and breakaway, self-sealing fuel lines.”

In May 1968 the Navy issued a final report on the system, concluding that:

“An in-flight personnel recovery system for helicopters is feasible and practical. Previous tests have demonstrated the feasibility of the concept, and subsequent advancement in the state-of-the-art ballistically deployed and opened parachutes combined with retro-rockets has made the concept efficient and practical.”

In September 1968, NAVAIR proposed a development program in order to pursue the capsule system. This pushed for designing a system applicable to rotary-wing aircraft to be used in the 1975-1980 timeframe, and retrofitting CH-46D aircraft with the escape system. It was estimated that the program would cost $5.3 million (nearly $48 million adjusted for inflation in 2024 dollars) over four years, and could have the potential to “ensure the survival of over 80 percent of helicopter occupants involved in emergency situations.” However, the program was never funded.

NAVAIR went on to propose a new development plan in December 1969 — named the Helicopter Escape, Protection and Survival System — which included a nine-year advanced development program costing some $14.4 million (over $123 million adjusted for inflation in 2024 dollars). This included the development of both the escape capsule and individual-type escape systems, in the form of ejection seats or other unitary extraction methods.

Unlike the 1968 plan, the retrofitting of CH-46Ds with escape systems was abandoned, with the emphasis turning to working on survival systems for future aircraft.

Into the early-1970s, however, enthusiasm for the idea of a multi-person helicopter escape module waned. In March 1972, the Navy revealed to a subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations that the program was of “low priority,” primarily due to the added weight of fitting the system onto aircraft and the subsequent impact on payload capacity and range. Cost concerns were also noted, alongside issues over maintenance.

1972 also marked a shift by the Navy toward exploring individual escape systems from aircraft more thoroughly. Individual escape systems were worked on by the Navy during the previous decade, it should be noted, with emphasis on creating escape methods for those flying on Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters. However, despite these plans picking up in the early 1970s, they did not end up coming to fruition.

These days, few helicopters feature crew escape systems. A notable exception to the rule is the Russian Ka-52 attack helicopter. This system involves jettisoning the main rotor blades and explosive cord detonating the canopy, before crew members are ejected from the helicopter. Other systems that use parachutes to recover the whole aircraft, crew included, like the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) have seen widespread use and many successful saves.

So there you have it, the intriguing — if little-known — history of the Navy’s attempt at fielding an in-flight personnel escape capsule for helicopters.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com