The rapid pace of development across China’s military aircraft scene has been well documented, with Western observers keenly awaiting new designs and variants of existing ones, while manufacturing plants keep up a seemingly relentless pace of deliveries. What’s been less well covered, however, is the domestic production of air-launched weapons to arm these aircraft. For many years, Chinese progress in air-to-air missiles, or AAMs, in particular, was overlooked or achievements downplayed.

In many cases, Chinese AAMs were discredited as mere knockoffs of existing Western designs. More recently, however, there has been a broader acceptance that Chinese AAMs are not only keeping pace with their rivals but, in some cases, offering performance that exceeds them. With the United States, in particular, working to close the gap with China’s long-range AAMs, now is a good time to review the air-to-air weapons that arm the combat aircraft of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

The following review looks at the background of Chinese AAM development followed by the most important domestically produced air-to-air missiles in PLA service today. At the same time, it’s worth bearing in mind that China also received considerable stocks of Russian-made AAMs, too, primarily to arm its Sukhoi Flanker-series fighters. These weapons include the R-27 (AA-10 Alamo), R-73 (AA-11 Archer), and R-77 (AA-12 Adder), although these are increasingly giving way to Chinese weapons, with Flankers from both Russian and Chinese production being optimzed to use them.

Early designs

Before considering the domestically produced AAMs that can be found arming PLA combat aircraft, and their export equivalents, today, it’s worth looking back at China’s earlier developments in this field. For many years, after all, Chinese-made AAMs were probably the least understood weapons in this class, with even less information available than Soviet designs.

China’s very first AAM was indeed a copy of a Soviet weapon. The PL-1 was based on the Soviet RS-1U (AA-1 Alkali) which was a primitive beam-riding missile used on some of the first Soviet-made jet fighters. The missile was originally supplied to China by the Soviet Union, prior to the Sino-Soviet split, but does not seem to have seen much use.

Very likely, the PLA’s dissatisfaction with the RS-1U had become apparent after clashes with Taiwanese F-86s in 1958 when the infrared-guided AIM-9B Sidewinder was first encountered in combat. While China launched domestic production of the PL-1 in the late 1950s, apparently with Soviet assistance, attention soon switched to a weapon in the same class as the AIM-9B.

The PL-2 was not a direct copy of the Sidewinder, but it was based on the Soviet R-3S (AA-2 Atoll), which was itself heavily inspired by the AIM-9B, with development aided by the wreckage of one of the Taiwanese missiles that Beijing shared with Moscow.

Like the AIM-9B, the R-3S and PL-2 were strictly limited, first-generation infrared-guided AAMs, only of practical use in tail-chase engagements. However, while the Soviets began developing new heat-seeking AAMs, China stuck with the basic PL-2 design and attempted to improve that. This led to the PL-5, which had an incredibly long development period, but one that was not atypical of Chinese military projects during the Cultural Revolution.

Work on the PL-5 began in 1966 and it only entered production in 1982. Initially, the PL-5 had been considered with semi-active radar homing (SARH), like the U.S. Navy’s AIM-9C, but in its ultimate form, it was another infrared-guided weapon, designated PL-5B. In the mid-1980s it was superseded by the improved PL-5C, and finally the PL-5E-II in the early 1990s. This last model reportedly has much-improved high-off-boresight capabilities (an off-boresight angle of +/-25 degrees before launch), conferring all-aspect performance. It also features a laser proximity fuse.

PL-8

By the early 1980s, it seems to have become clear that the PL-5 offered only limited development potential and was outclassed by both Soviet and Western designs. In response, China began work on a new infrared-guided AAM, the PL-8. Since this missile looks almost identical to the Israeli Rafael Python 3, it’s frequently described as a copy, but the truth is more complex. In fact, it seems the PL-8 emerged from a period of Sino-Israeli cooperation during the 1980s. In particular, Beijing had been impressed by the performance of the Python 3 over Lebanon in 1982 and requested a technology transfer.

Reportedly, Israel provided kits for licensed production of the Python III in the late 1980s, before China began full domestic manufacture, as the PL-8A, in the late 1990s. This was followed by the PL-8B, first observed in 2005, and fitted with a new all-aspect seeker for a wider off-boresight angle and its range increased to around 12 miles.

Importantly, the latest PL-8B is also compatible with Chinese-made helmet-mounted sights. These sights can now be found on a wide variety of PLA fighters, including the J-10, the Flanker series, and the J-20, providing a true dynamic high-off-boresight targeting capability via the pilot looking at the target for the missile to acquire it.

PL-10

While the PL-8B remains in widespread service, the PLA’s latest dogfight missile, the PL-10, also known as the PL-Advanced Short-Range Missile (PL-ASRM), is an altogether more advanced weapon that’s judged to be at least equivalent to Western weapons in its class.

The PL-10 incorporates an imaging infrared (IIR) seeker, thrust-vectoring exhaust nozzle, laser proximity fuse, and reportedly boasts a 90-degree off-boresight capability. Overall, IIR seekers offer a range of significant benefits, including improved target detection range and better resistance to countermeasures.

There have been claims made that the PL-10 has a lock-on-after-launch, or LOAL, capability, which would allow it to hit targets at greater distances, with target data being relayed by datalink while in flight. This capability is also critical for stealthy aircraft that carry their weapons concealed in internal bays.

However, the J-20 employs the PL-10 from launch rails that deploy outside of the side weapons bays, projecting the missiles into the slipstream, but with the bay doors closed. This approach seems to have been chosen as an alternative to LOAL as well as a quicker method of launching the weapons during shorter-range engagements. You can read more about the novel concept here. It’s very possible that later versions of the PL-10 will feature LOAL capability but that it was not available when the J-20 was designed and first fielded.

The missile is also compatible with helmet-mounted sights from the outset, allowing all-aspect shots at very high G-loadings.

Development of the PL-10 began around 2005 with a reported first test launch in late 2008 but the missile also underwent an extensive redesign. Apparent production examples began to appear on PLA J-11 Flanker fighters in 2011 although most reports suggest it entered service after that date, perhaps shortly before its public debut at the Zhuhai Airshow in 2016. Since then, it’s been gradually replacing the PL-8B as the PLA’s standard short-range AAM.

The U.K.’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) defense think tank considers the PL-10 “comparable to the European ASRAAM and IRIS-T missiles, with superior kinematic performance to the American AIM-9X Sidewinder.”

There are unconfirmed reports that China is now working on a successor to the PL-10, sometimes known by the designation PL-16, but no details are available.

PL-11

While sequentially the next Chinese AAM, the PL-11 actually dates back much farther to Beijing’s first efforts to field a medium-range weapon with semi-active radar homing (SARH) coupled with inertial guidance. This method of guidance requires the launch aircraft to illuminate the target using its own radar during the final stages of the engagement.

It seems that these attempts at first focused on trying to reverse-engineer the AIM-7 Sparrow, without success.

In the mid-1980s, however, China acquired the Alenia Aspide Mk 1 surface-to-air missile from Italy, this essentially being similar to the AIM-7E. After securing a license to produce the surface-launched Aspide Mk 1, China then went about developing this as an AAM, known as the PL-11. Despite the Tiananmen Square massacre bringing an abrupt end to cooperation with Italy (and with the United States), development continued and test firing of the AAM from a J-8B Finback fighter began in 1992.

In common with the Aspide Mk 1, and unlike the AIM-7E, the PL-11 has an inverse monopulse seeker, which should make it more accurate and less susceptible to electronic countermeasures.

Service entry of the PL-11 followed in the mid-1990s, but it seems that the weapon was only fully cleared for service in around 2001, by which time it was judged obsolescent.

PL-12

The PL-11 was issued only to J-8 and J-10 units, work had been underway since the early 1990s on its planned successor, the PL-12, which was intended as a Chinese answer to the AIM-120 AMRAAM.

Like the AMRAAM, the PL-12, the development of which was launched in the early 1990s, features active radar homing, providing a ‘fire and forget’ capability, as well as a datalink for mid-course updates. This relies on a miniaturized active radar seeker, plus a datalink, which some accounts suggest were developed with Russian assistance.

The PL-12 is slightly larger overall than the AMRAAM and its tail-mounted control fins feature characteristic notches cut into them at the base.

Reports suggest that the PL-12 uses a variable-thrust rocket motor to ensure speed and maneuverability across the flight envelope, and that the PLA considers it superior to the AIM-120B and the Russian R-77 (AA-12 Adder), although marginally less capable than the more advanced AIM-120C.

The PL-12 was approved for service in 2005 and was first issued to J-8F units, before being introduced on the J-10, J-11B, J-15, J-16, Su‑30MK2, and the J-20. The missile is also offered for export as the SD-10, which is used on JF-17 Thunder fighter jets operated by Myanmar, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

An improved version, the PL-12A, reportedly features a modified seeker with a new digital processor and is claimed to be comparable to the AIM-120C-4. Unconfirmed reports suggest the new version may also have a passive mode for homing in on jammers, electronic warfare emitters, and airborne early warning aircraft.

According to official specifications, the PL-12 has a range of between 44 and 62 miles, reduced to 37-44 miles for the export-configured SD-10. RUSI assesses that the PL-12’s range “sits somewhere between the AIM-120B and AIM-120C-5.”

There have been rumors of other more advanced variants, too, including one with folding fins for internal carriage, one with an anti-radiation seeker head, and a ramjet-powered version for long-range engagements. None of these appear to have progressed to operational service. Interestingly, the Pentagon’s latest report to Congress on Chinese military developments, from last year, states that China is “developing a ramjet-powered AAM in addition to the beyond-visual-range PL-15,” although there does not seem to be any wider evidence of this.

PL-15

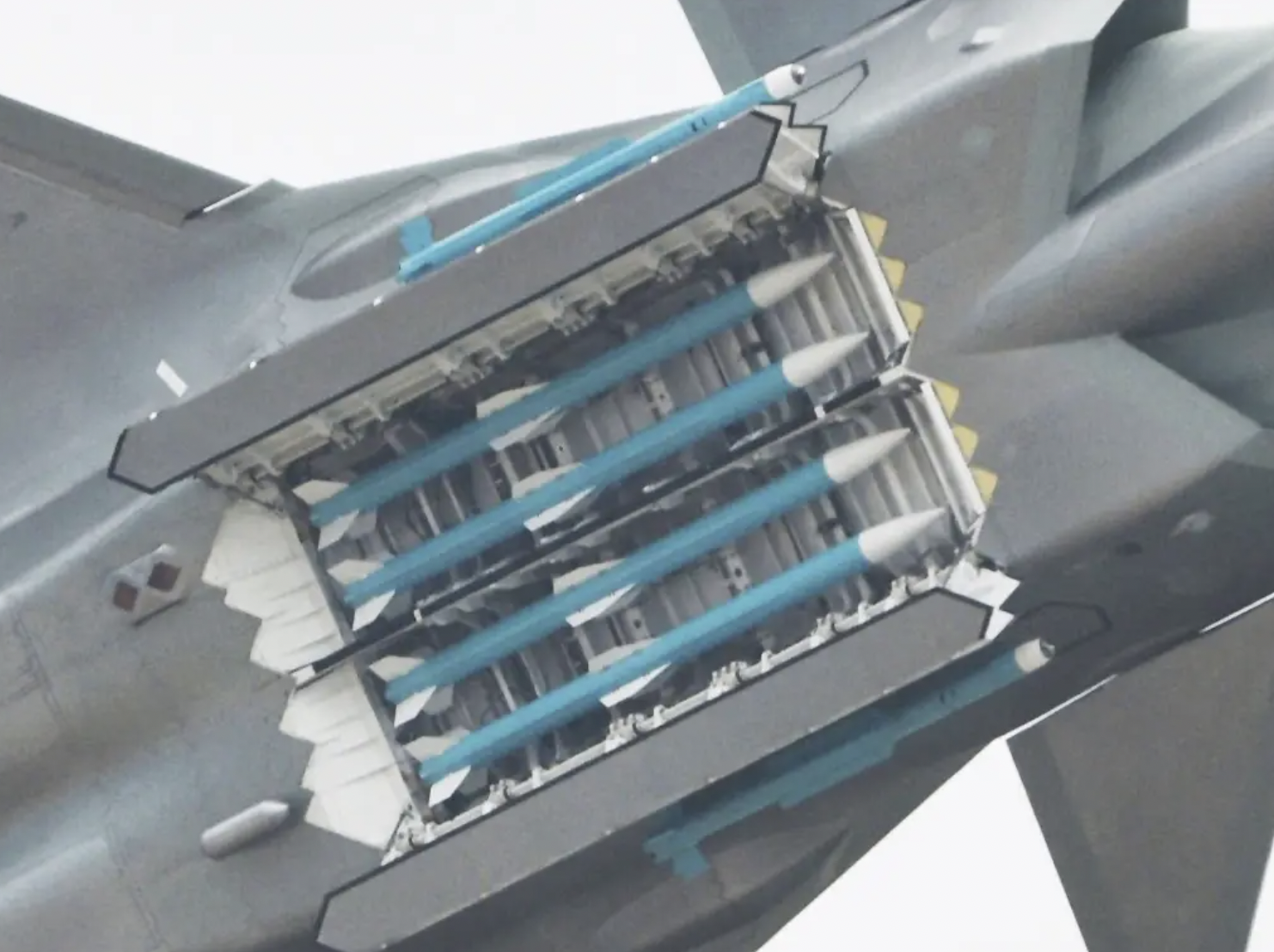

While exotic versions of the PL-12 did not make it into service, China was already busy working on a new active radar-guided AAM, the PL-15, apparently intended to at least match the performance of the AIM-120D. From the start, this missile was tailored for internal carriage, initially in the J-20, and features distinctive cropped fins to reduce its dimensions.

More significantly, however, the new missile employs a dual-pulse rocket motor that helps boost its range to a reported 124 miles. A two-way datalink provides guidance updates to the missile and the launching aircraft and the seeker uses active electronically scanned array (AESA) technology, with active and passive modes, and it’s also said to have better resistance to countermeasures.

The PL-15 likely began development in around 2011 and was first seen in the form of a test missile carried by a J-11B the following year. From 2013 onwards it began to appear in the main weapons bay of the J-20 before that type was formally inducted. Operational service for the PL-15 is thought to have commenced in late 2016, the new missile initially arming the J-10C and J-16. The missile has also been seen on the J-11B, suggesting that these aircraft are being modified for compatibility, and the carrier-based J-15 is also a likely recipient in the future.

The PL-15 is currently replacing the PL-12 across the PLA’s fighter fleet and has also been offered for export under the PL-15E name. The first customer for the export model is Pakistan, to arm its JF-17 Block III and J-10C fighters.

Published performance figures for the PL-15E include a range of 90 miles, somewhat less than for the domestic version, which could be as the result of a different propellant or changes to the motor.

Regardless, RUSI determines that the PL-15 “out-ranges the US-made AIM-120C/D AMRAAM series and has a comparable maximum range to the Meteor.” The same source notes, however, that the pan-European Meteor likely has a much larger no-escape zone and better long-range kill probability thanks to its ramjet motor. At least partly in response to the PL-15, the United States has embarked on a program of improvements for its AIM-120D, creating a stopgap weapon before the new long-range AIM-260 enters widespread service. The AIM-260 program itself was also largely a response to Chinese AAM developments.

PL-XX (PL-17 or PL-20?)

While the PL-15 is widely seen as the successor to the PL-12, there is also another AAM program currently under development, although details about it remain limited.

Normally known in the West as the PL-XX, this is thought to be a very long-range AAM, perhaps intended primarily to target high-value assets, like tankers and airborne early warning aircraft. Alternative designations could be PL-17 or PL-20, but they remain unconfirmed.

It seems likely that the project superseded plans for a ramjet-powered version of the PL-12, or a rival PL-21 also with a ramjet motor. The chosen new weapon instead opted for a dual-pulse rocket motor, which should have made it easier to master in technological terms.

The missile that resulted is significantly longer and broader than the PL-15, with a length of almost 20 feet. It uses a combination of four small tail fins and thrust-vectoring controls for maneuvering and is reported to have a range in excess of 186 miles, with a top speed of at least Mach 4. Guidance is thought to be achieved through a combination of a two-way datalink and an AESA seeker, which is said to be highly resistant to electronic countermeasures. With such long ranges involved, most engagements would be expected to involve targeting data provided by standoff assets, such as friendly airborne early warning aircraft, other aircraft closer to the target, ground-based radar or even satellites.

A possible optical window on the side of the nose of the missile could indicate an additional infrared seeker, which would make it far harder to defeat as it would be immune to heavy jamming in the terminal phase of the engagement. This is an established configuration, so it wouldn’t be surprising if it was adopted for such a large AAM concept.

The size of the PL-XX means that for now at least, it’s restricted to external carriage. The weapon was first identified on the J-16, and in November 2016 was successfully fired from this type. The AAM may well be compatible with other Flanker-series fighters and could potentially be carried externally on the J-20. However, the current status of the weapon is somewhat unclear, with testing apparently ongoing as of 2020 but no confirmation, so far, of official service entry.

Overall, China has made rapid progress in its development of air-to-air missiles, paralleling improvements in its combat aircraft fleet and, in some cases, offering capabilities that are not totally matched by comparable Western or Russian products.

According to most sources, its latest air-to-air weapons have allowed China to approach parity with Western equivalents, even exceeding parity in some areas, while significantly surpassing Russian missiles. On the other hand, the testing regime and developmental infrastructure available in the West are still likely to provide certain advantages in terms of real-world effectiveness for AAMs. The same can be said for networking infrastructure increasing the flexibility and capabilities of next-generation ‘networked’ AAMs — for now, at least. In the meantime, it is almost certain that China, too, has several new AAM programs in the works, although sorting rumor from reality is not easy in this regard. The country also continues to invest in expanded testing and developmental infrastructure that increasingly mirrors that of the West.

As well as its AAMs following a logical progression in terms of steadily improving performance and capabilities, China has also been introducing them together with complementary sensors, including AESA radar, low-observable technologies, plus modern cockpits with helmet-mounted displays. The result has essentially seen China leapfrog Russia as the leading near-peer aerial pacing threat that the U.S. and many of its allies will likely have to contend with in the decades to come.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com