Of all the issues surrounding the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, perhaps the most hotly contested is the criteria the U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy are using to judge when the jets will be ready for combat and whether certain milestones accurately reflect the stealth fighter’s capabilities. The Air Force has now reignited this debate by stating that it will have “fully combat capable” F-35As by the end of September 2017 even though the jet hasn’t even started independent operational test and evaluation trials.

On Aug. 25, 2017, Aviation Week reported that the Air Force would begin receiving A model aircraft able to “employ its full suite of air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons,” including its internal 25mm cannon. To achieve this milestone, the new aircraft would come with a critical new software update, which the service referred to simply as Block 3F. In September 2016, the service announced this would occur by the beginning of the 2018 fiscal year, which starts on Oct. 1, 2017.

“We now just passed 100,000 flying hours with the F-35, and it is doing very well,” Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson told reporters during a press conference, also on Aug. 25, 2017. “In any contingency, if there were a problem, they’re ready to go – ready to go to combat.”

Wilson was responding in part to questions about Air Force capabilities to respond to heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula, where North Korea continues to test advanced ballistic missiles and has now claims to have a functional hydrogen bomb. On Aug. 31, 2017, Marine Corps F-35Bs, which the service has forward deployed to Japan, joined a show of force over both Japan and South Korea for the first time.

As we at The War Zone have noted before, low observable aircraft such as the F-35 would be an important component of any actual strike on North Korea, owing to the country’s dense, if dated air defense network. A fully-combat capable Joint Strike Fighter would give Air Force commanders in the Pacific, as well as other hot spots

around the world, additional flexibility to respond to crises.

The 34th Fighter Squadron at Hill Air Force Base in Utah, a combat coded unit, is slated to receive the jets with the Block 3F software first, according to Aviation Week. The three training squadrons at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona – the 61st, 62nd, and 63rd Fighter Squadrons – will then start getting the updated aircraft.

Still, it’s not entirely clear how the Air Force is defining “fully combat capable” in this case. None of the three F-35 variants have even begun the mandatory testing process run by the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E), which is independent of the individual services.

What is clear is that this is not the same, nor is the service claiming it is, as a formal declaration of “full operational capability,” or FOC. The Pentagon-standard definition for FOC is when every unit that is supposed to receive a certain weapon system has gotten that piece of equipment and can both operate and maintain it. This announcement is generally only supposed to come after the system passes DOT&E’s rigorous independent testing regime.

The Air Force had already added confusion to this process by declaring initial operational capability (IOC), which is supposed to reflect a basic operational capability, for the F-35A before the end of developmental testing and without any operational evaluations. The service seems to be again obfuscating the situation, intentionally or unintentionally, by using a term that sounds similar to FOC, but isn’t, which has already led to confusion

in the media about what this new announcement realistically means.

“This may very well be an effort to undermine the operational testing process,” Dan Grazier, the Jack Shanahan Fellow at the Project On Government Oversight, a non-partisan watchdog that has been highly critical of the F-35 program, told The War Zone by Email. “All the services have been hostile to the idea of having an outside testing official evaluating their work. I see this as an attempt to marginalize DOT&E’s role in the acquisition process.”

Of the three services purchasing F-35 variants, the U.S. Navy is the only one that has not declared IOC with its jets, continuing to link that milestone to the successful completion of operational testing. The U.S. Marine Corps and the Air Force say they have achieved this with their F-35s and now the Air Force curiously says it plans to declare IOC for the Block 3F software itself once the code begins reaching operational and training units.

“Declaring ‘initial operational capability’ after each of the program’s steps rather diminishes the pronouncement,” Grazier added. “I’m sure most people are really only interested in ‘full operational capability’ as that is what we are paying for.”

Beyond that, based on the publicly available information, it’s hard to say whether or not the Block 3F software package will provide a truly complete suite of combat capabilities. We have no reason to doubt the new code will finally allow F-35A pilots to employ the fuller range of existing operational weapons the Air Force wants the aircraft to carry by the end of the ongoing developmental testing process.

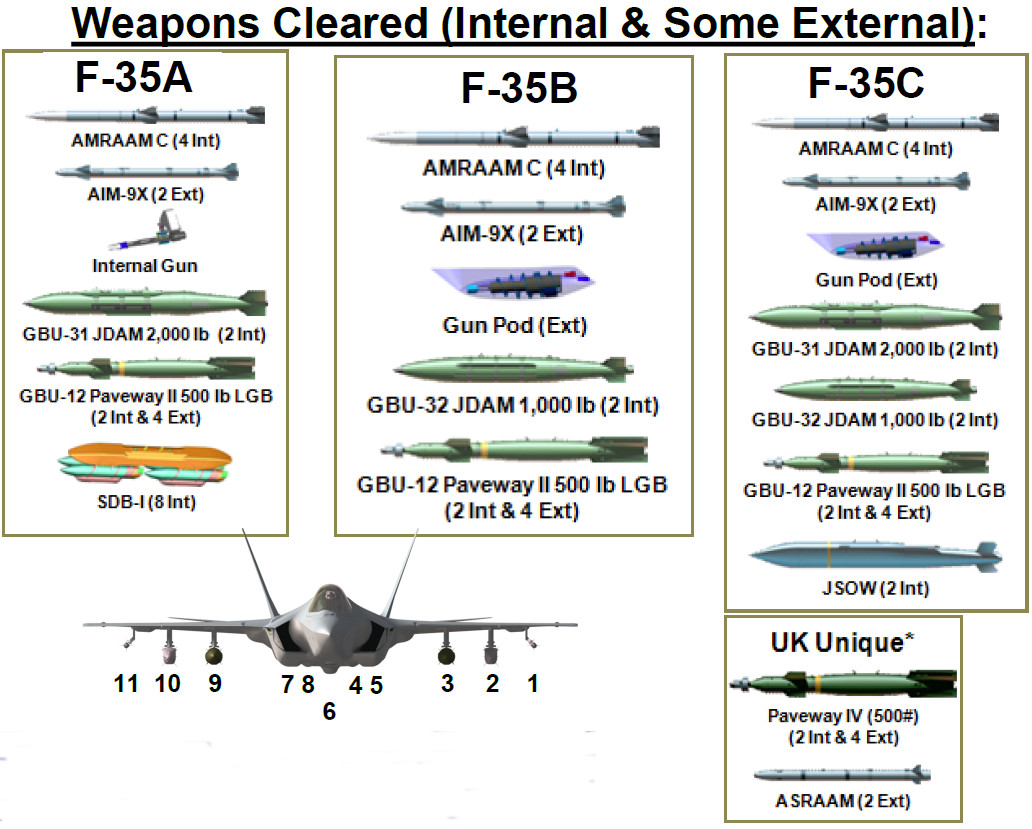

As of 2015, this list of planned weapon options was relatively short, including the AIM-9X and AIM-120C air-to-air missiles, GBU-12/B 500-pound class laser-guided bombs, GBU-31/B 2,000-pound class GPS-guided Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bombs, the GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb (SDB), and the GAU-22/A 25mm cannon. There are now plans to integrate 500- and 1,000-pound class JDAMs and the GBU-49/B dual-mode version of the GBU-12.

The F-35As can only carry some of these weapons, such as the AIM-9X, on external pylons that severely degrade the aircraft’s low-observable characteristics. The Air Force hopes its final, full operational capability Joint Strike Fighters – running the still notional Block 4 software – will be able to carry dual-mode Laser JDAMs and the still-in-development SDB II, as well.

That being said, there’s no guarantee that the Block 3F software will allow F-35A pilots to effectively employ some or all of these weapons. We don’t even know for sure what specific version of it the Air Force will distribute for its software “IOC.”

As of December 2016, the service had already gone through six different revisions of the update. According to DOT&E’s annual report on the program for 2016, the central joint service F-35 program office initially planned for this latest code, known as Block 3FR6, to be ready in February 2016, but it only arrived 10 months behind schedule.

In 2016, “DOT&E reported there were 270 high-priority deficiencies in the Block 3F software for each variant [of the F-35],” Grazier noted. “The Air Force’s own test pilots rated the Block 3F as ‘red’ or not ready for operational testing, not to mention actual combat, in all mission areas.”

It is important to note that what specifically the Air Force had negatively rated was two subversions of the earlier Block 3FR5 software, 3FR5.03 and 3FR5.05. It is possible that the present edition of Revision 6 has fixed most, if not all of the issues.

However, it’s hard to give the service the benefit of the doubt that this has been the case. As with the Block 3FR5 software, Air Force itself determined the Block 3i package for the IOC jets was unacceptable for actual combat operations, according to DOT&E’s review of the program. This prompts serious questions about the validity of Air Force Secretary Wilson’s comments in August 2017, as well as the IOC decision itself and what we can expect from the new 3FR6 code.

This is further compounded by the fact that the Air Force says it already expects to deliver a string of Block 3F updates as continued testing exposes more problems despite its insistence that they will have “full combat capability.” This is actually something DOT&E recommended the F-35 program as a whole do after developmental phase ended, but as part of the subsequent operational evaluation process and before any service even considered deploying the jets on operational missions or training exercises – something both the Air Force and Marine Corps have now been doing for months.

“Several essential capabilities – including aimed gunshots and Air-to-Air Range Infrastructure – had not yet been flight tested or did not yet work properly when Block 3FR6 was released,” according to DOT&E’s review. “The services [Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy] … designated 276 deficiencies in combat performance as ‘critical to correct’ in Block 3F, but less than half of the critical deficiencies were addressed with attempted corrections in 3FR6.”

On top of that, DOT&E said that the delays with Revision 6, coupled with funding problems, had forced the F-35 program office to scrap its own existing plans for two follow-on software blocks, 3FR7 and 3FR8. At this point, it seems almost impossible to assess the true capabilities of any “Block 3F” code, positively or negatively, based on public descriptions, especially given the sheer number of major revisions and minor changes.

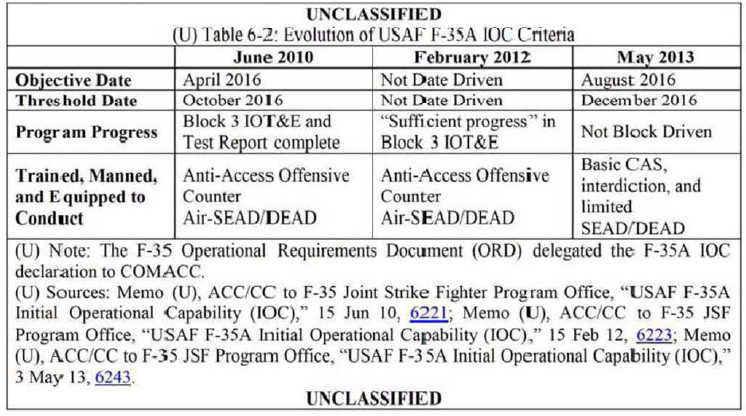

But most significantly, thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, we do know that the service already deliberately watered down its capability criteria to meet its own, self-imposed schedule for declaring IOC with the F-35A in August 2016. This was mainly out of fear that delaying the milestone any further would become a political and public relations nightmare that could’ve potentially impacted Congressional support and foreign sales.

In June 2010, the official schedule was to have a final version of the Block 3 software pass the independent operational test and evaluation process no later than October 2016 and then make the IOC announcement. By May 2013, this had changed to having an aircraft ready with any block of software that would allow pilots a limited capability to destroy enemy air defenses and perform basic close air support, with no mention whatsoever of air-to-air combat. At present, the Air Force does not have a firm date of when the jets will be ready for the more rigorous operational testing and evaluations.

It is entirely possible we’re seeing this situation crop up again. The Air Force’s statements came ahead of the Labor Day holiday weekend and before Congress returned to continue work on, among other things, the defense budget for the 2018 fiscal year.

“The Senate version [of the annual National Defense Authorization Act] would have the American taxpayers purchase 94 F-35s, 24 more than the president requested,” Grazier noted. “I am sure this move is an effort to make people believe the program is worth the investment.”

This argument would help explain why the U.S. Marine Corps made a similar declaration shortly after the Air Force announcement. The service said that their F-35Bs in Japan would also be getting some version of the Block 3F software, gaining a similar full combat capability to the Air Force models.

None of this is to say that the ultimate version of the Block 3F software won’t perform as required and provide the services with an F-35 that is highly capable, one that is even ready for combat in an emergency. The concern is that the rush to get the jets into service could put pilots in the seat of a jet that just isn’t ready yet, exposing them to unnecessary risks, which is why the operational test and evaluation process exists in the first place.

This does means the F-35 program isn’t necessarily progressing forward and meeting its goals, either. However, as we at The War Zone have noted before, it can be difficult to judge official statements regarding the Joint Strike Fighter, which often seem to rely on obtuse and “technically correct” claims that confuse the obvious and significant issues that project continues to face, often serving to diminish any actual positive news that emerges.

Back in July 2017, Tyler Rogoway noted this after the Navy released some of the most candid and useful official information to date about test of the Marine Corps’ F-35B, writing:

After watching this video, it’s hard not feel that if the F-35 program would have just consistently published this type of information as the program advanced, for better or worse, it probably would have gone a long way to help – not hurt – the controversial aircraft’s plight.

One of the major criticisms of the F-35 program has been the fog surrounding its delayed development. Massive swathes of issues would periodically emerge through leaks, congressional hearings, and watchdog or pentagon test and evaluation reports. At the same time, straight answers from the aircraft’s manufacturer or the F-35 program office were seemingly few and far between. Instead, we got glitzy videos with idealized snippets of the jet in action and those involved with the program singing its praises, which seemed totally tone deaf, especially as the aircraft’s development was clearly headed towards the edge of the abyss.

One has to wonder whether the Air Force and the Marines Corps are now making the same mistake by trying to drum up support for the aircraft with this largely undefined claim, which is undoubtedly technically accurate based on the services’ internal criteria, of fielding fully combat capable F-35s before the independent operational test and evaluation process has even begun.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com