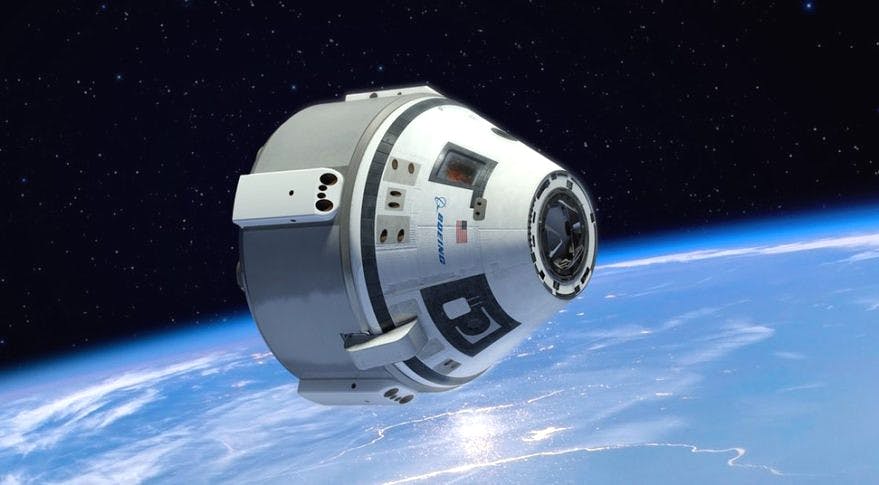

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft, which could carry astronauts and cargo to the International Space Station in the future, failed to reach the correct orbit to link up with that station during its first orbital flight test today. Automated systems on the uncrewed CST-100 thought the craft was in a different position than it actually was, leaving it in a stable orbit, but out of position and low on fuel. Mission controllers are still in control of it remotely and are planning to bring it down at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico before the weekend is over.

NASA says the launch took place as planned at 6:36 AM this morning, with a United Launch Alliance Atlas V space launch vehicle with the Starliner on top blasting off successfully from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The CST-100 separated from the upper stage of the Atlas V as intended 15 minutes after launch, at which point it was not yet in orbit. This is intended to allow time to safely abort a mission, if necessary. The spacecraft then used its own four thrusters to boost itself into orbit.

“The Boeing Starliner space vehicle experienced an off-nominal insertion. The spacecraft currently is in a safe and stable configuration. Flight controllers have completed a successful initial burn and are assessing next steps,” Kelly Kaplan, a Boeing spokesperson subsequently, told reporters. “Boeing and NASA are working together to review options for the test and mission opportunities available while the Starliner remains in orbit.”

You can watch the full NASA live stream of the launch and the Starliner’s failure to reach the right orbit below:

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine later further explained on Twitter that what had happened was a “Mission Elapsed Time (MET) anomaly,” meaning that “Starliner believed it was in an orbital insertion burn (or that the burn was complete), the dead bands were reduced and the spacecraft burned more fuel than anticipated to maintain precise control.” Having expanded too much fuel in the initial ascent into orbit, the CST-100 did not have what it needed to get into the appropriate orbit to meet up with the International Space Station (ISS).

NASA and Boeing are now working to bring the Starliner down safely at White Sands, which is where it was originally expected to land on Dec. 28 after completing its planned mission. The craft is carrying Christmas gifts that had been intended for the six astronauts on the ISS, half of which are presently Americans. It also had tree seeds similar to the ones that the Apollo 14 mission brought to the Moon and an ID card that belonged to Boeing founder William E. Boeing.

Though there was no one on board the Starliner for this inaugural orbital mission, it is carrying a mannequin dressed as “Rosie the Riveter,” the iconic representation of women who worked in factories, especially those supporting the war effort, during World War II. This surrogate was also packed full of sensors to gather data on the stresses human occupants might experience during future missions. The entire launch and rendezvous with the ISS was supposed to provide an end-to-end test of the CST-100 ahead of a first crewed mission that is presently scheduled to take place sometime in the first half of 2020.

NASA and Boeing say it’s too soon to tell whether or not another uncrewed mission will be necessary now to validate the craft’s general functions. NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said at a subsequent press conference that had astronauts been on board during this flight, they might have been able to detect and correct the anomaly before it became an issue.

Starliner also completed a successful sub-orbital abort test in November. Boeing is competing against SpaceX, and its Crew Dragon spacecraft, for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program contract, which seeks to develop an all-American alternative to the present practice of using Russian-made space launch vehicles and spacecraft to deliver personnel, as well as cargo, to the ISS. Relying on Russia for these services has become increasingly complex in recent years due to worsening relations between Moscow and Washington.

Both companies have suffered delays since securing their initial contracts to develop prototype systems in 2014. The SpaceX Crew Dragon did successfully conduct its first uncrewed mission to the ISS in March, two months later than originally expected. The company had expected to perform its own in-flight abort test in April, but the spacecraft it planned to use in that test was destroyed when one of its SuperDraco thrusters exploded during a static engine test that same month.

It’s far too soon to tell exactly how serious the technical problems that scuttled the CST-100’s first uncrewed mission are in the end. At the same time, it does come more than a year after NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel publicly criticized both Boeing and SpaceX over what it said were unrealistically short timelines for achieving an actual, operational capability.

“We have not seen the [Commercial Crew] program make decisions detrimental to safety,” Patricia Sanders, head of the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, said in October 2018. “But current projected schedules for uncrewed and crewed test flights for both providers have considerable risk and do not appear achievable.”

Crew Dragon and CST-100 are each still scheduled to bring astronauts to the ISS in 2020. Failure to do so on time could put the space station in an extremely precarious situation, which you can read about in much greater detail in this past War Zone story.

Of course, this is not to say that the Russians haven’t had their own issues in providing launch services to the ISS. In October 2018, a Soyuz-FG rocket suffered a technical problem, leading to its second stage breaking apart and forcing the two occupants of the Soyuz-MS crew capsule on top, Russian cosmonaut Aleksey Ovchinin and American astronaut Nick Hague, to conduct an emergency “ballistic descent,” which you can read about more in this previous War Zone story. Thankfully the capsule touched down safely and Ovchinin and Hague survived.

“We’re talking about human spaceflight,” NASA Administrator Bridenstine noted during the press briefing about the CST-100 mishap. “It’s not for the faint of heart. It never has been, and it’s never going to be.”

There are also questions about whether the United States remains committed to the ISS and whether it might look to rent its space on the station to private entities starting after 2025. The U.S. government relaxed rules on its ability to commercializing the ISS, which could include taking on privately-funded projects, accepting corporate sponsorships, and even selling tickets for private citizens to go to the station, in June.

Without life-extending upgrades, the ISS may not even be a viable platform for work in space after 2028, by which time the United States may have moved on to plans for its own new space station. The U.S. government is also looking to restart manned missions to the Moon and has also expressed its eagerness to eventually send astronauts to Mars.

In the meantime, Boeing and SpaceX will continue working toward launching the first crewed missions of their respective spacecraft up to the ISS, which will usher in a new era of American space travel…

Eventually.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com