As Australia waits for its 12 new, controversial Attack class submarines, the country’s defense ministry has announced that it will spend around $4.6 billion keeping its current fleet of Collins class submarines viable until they can be replaced. Previous plans would have modernized just three of the Collins class, but the ministry has been forced to make the move since the first of the Attack class is not now expected to be delivered until around 2035, while the full fleet won’t achieve final operational capability (FOC) until 2054.

Australia’s Minister of Defense Peter Dutton confirmed the plans for a life-of-type extension (LOTE) for the six Collins class submarines, as reported by the Defence Connect website. It’s a significant investment in the aging Collins class design, the first example of which entered service in the mid-1990s and reflects the latest in an ongoing series of concerns about delays with the Attack class program, which was originally supposed to enter service in the early 2030s.

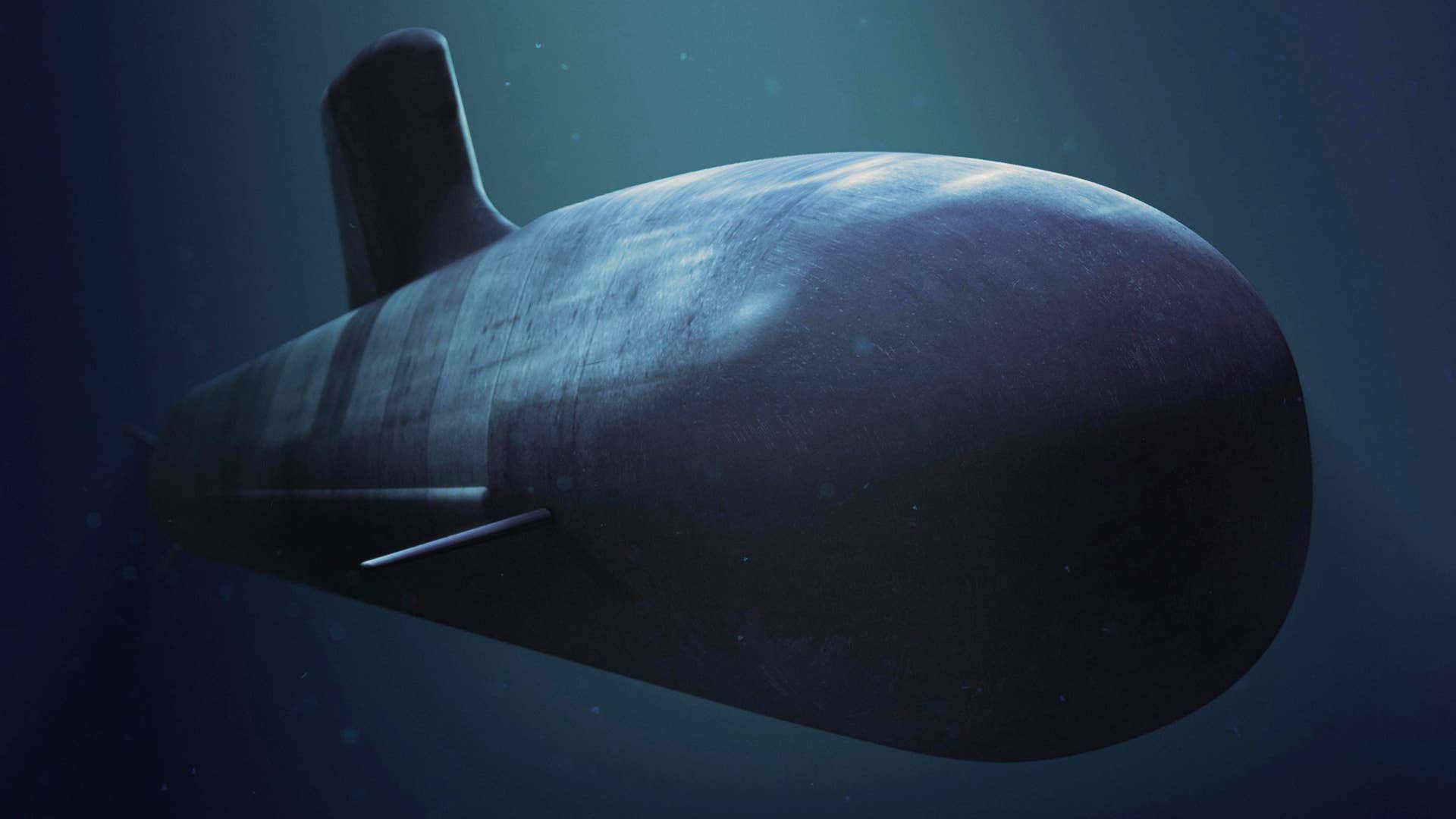

The Collins class submarines were designed by the Swedish firm Kockums, which is now part of Saab. These are large conventionally powered submarines, with a submerged displacement of almost 3,500 tons and a length of 254 feet. Details of the LOTE program have not been announced, but the plan is to ensure that the Collins boats remain suitable for combat operations until the Attack class is declared ready for frontline service.

“We need to be realistic about what lies ahead by way of threat in our own region, and the submarine capacity is a significant part of how we mitigate that risk and it’s important we get the program right”, Dutton told The Australian. “There is no doubt in my mind that we need to pursue a life-of-type extension [for the Collins class].”

LOTE work will commence on each Collins class submarine as it reaches 30 years of service, with a thorough rebuild that will take around two years per boat. According to Defence Connect, upgrade work will be carried out by ASC in Adelaide, which originally built the vessels, while the government confirmed by that Saab will be active in a supporting role. The first Collins is due begin undergoing the upgrade work in 2026.

Dutton admitted the modernization program presented “a tight timeline, no question.”

In the background to this latest development, there is still confusion as to the viability of the ambitious Attack class program, also known as SEA 1000.

Back in 2016, France’s Naval Group (then known as DCNS) won the SEA 1000 contract to replace the Collins class. The Naval Group’s Attack class submarine is a derivative of the Shortfin Barracuda Block 1A design. Equipped with advanced technologies, likely to include air-independent propulsion systems, as well as the AN/BYG-1 Submarine Payload Control System, the Attack class is enormously expensive — it’s now projected to cost around $69 billion. Back when the French submarine was selected the total program cost was projected to be a little under $40 billion.

The cost of the program, as well as worries about workshare for the Osborne Naval Shipyard in South Australia that will build the submarines, as well as technology sharing, has dogged the SEA 1000 project. The original agreement required at least 60 percent of the contract value to be invested in local industry.

Exactly why the program has become so expensive is not entirely clear and this lack of transparency on the financial issues has been a persistent source of conflict between the Australian and French sides. However, we do know that the $69 billion includes funds for research and development, integration of combat systems, establishing indigenous production facilities, plus support infrastructure. With that in mind, a unit cost of $8 billion per hull is somewhat misleading. On the other hand, the fact remains that two years ago France claimed that it had budgeted just over $10 billion for a total of six Barracuda class boats that it’s buying for its own navy.

Earlier this year, it was reported the Australian government was even thinking of canceling the contract with Naval Group entirely. Instead, thought has apparently been given to an alternative design based on the Collins class, to be built by Naval Group’s Australian subsidiary.

More recently, there have been reports that the government is also examining acquiring a German submarine — almost certainly the Type 216 submarine from Thyssen Krupp that lost out in the original SEA 1000 bidding — as an interim measure pending full availability of the Attack class. That would seem an extravagant solution but bearing in mind the Type 216 was expected to come in at around half the cost of the French design, it could potentially be feasible, albeit far more expensive than an upgrade to the Collins class.

Dutton noted that there had been “problems with the arrangements with Naval Group,” and assured that everything was being done to ensure that contractual obligations were being met. Nevertheless, all this only adds to the delays in actually putting the new submarines to sea and makes the need for an interim solution more urgent.

Earlier this month, as part of a wider overhaul of its leadership, Naval Group Australia brought in a new executive vice president for its Future Submarines program.

Clearly, Australia needs a replacement for its aging Collins class submarines, one way or another. While the costs of the Attack class may be eye-watering, the Royal Australian Navy recognizes the importance of submarines in modern naval warfare, in general, and to Australia, in particular, as a major Pacific naval power. This is especially relevant at a time when China is rapidly expanding its own navy and introducing submarines that are faster and harder to detect.

What seems to be the current favored solution — upgrading the existing Collins class while waiting to see what happen with the Attack class — seems risky, but it does at least give Naval Group another chance to put its program onto the right track. At the same time, local shipbuilding industry will be kept busy with repairs works to the older submarines at least until it can begin work on its successor. For now, that is still likely to be the Naval Group design, but talk of more than one alternative under consideration suggests that there is still potential, at least, that this might still change.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com