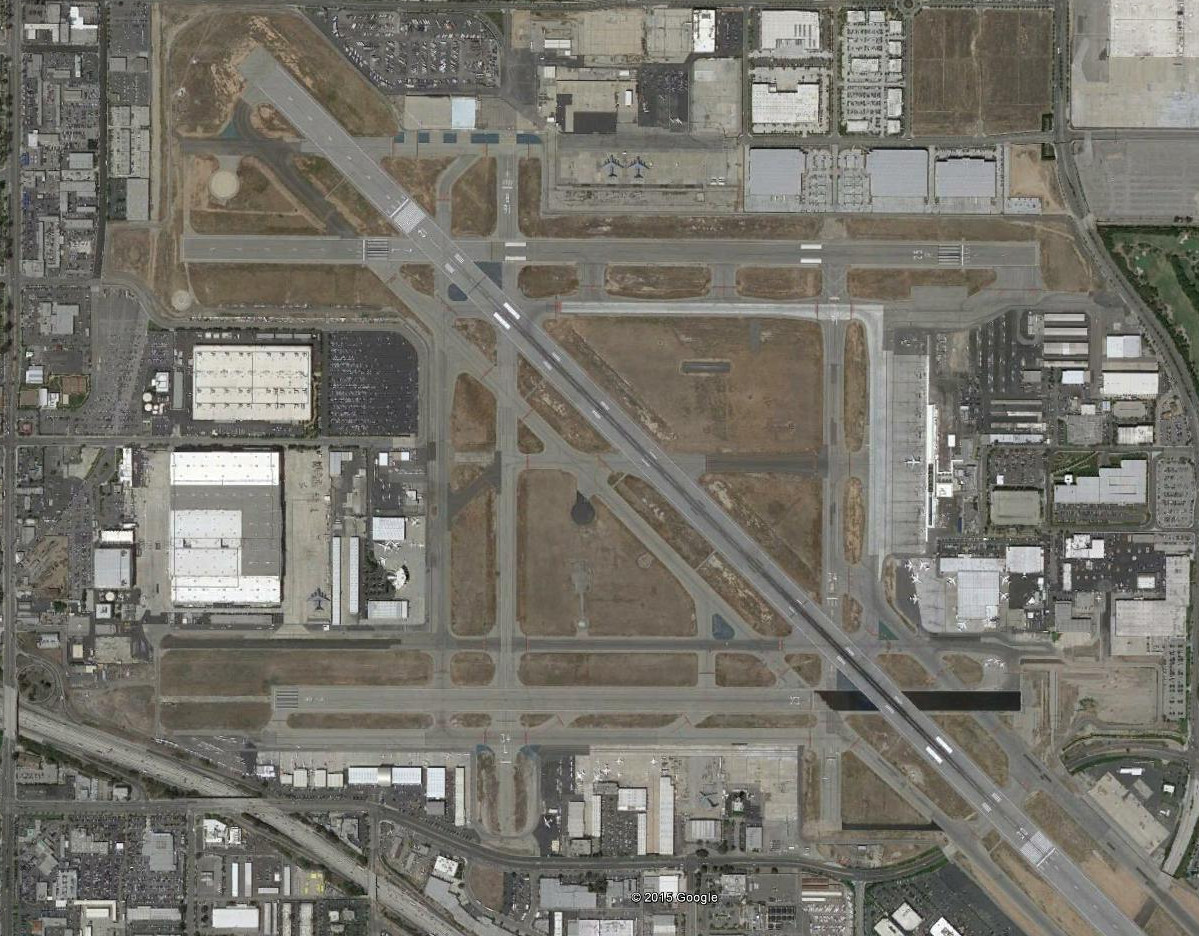

Boeing is looking to sell the facilities in Long Beach, California where it built the C-17A Globemaster III cargo aircraft. This will bring a more definitive end to the company’s serial production of military aircraft in Southern California and makes it even less likely that it would restart production of the airlifters in response to emerging U.S. Air Force demands. At the same time, that space could be very attractive to up-and-coming space launch firms, such as Virgin Orbit or SpaceX, who might be looking to expand their operations and there have also been proposals for a more dramatic overhaul of the area.

The Chicago-headquartered plane maker put the property on the market with the help of real estate brokerage NKF Capital Markets on Nov. 5, 2018. The nearly four million square foot plot of land adjacent to Long Beach Airport includes the 1.1 million square foot main assembly building where workers built just shy of 280 C-17s for the U.S. Air Force and more than a half dozen foreign customers. So far, there is no public asking price for the property.

McDonnell Douglas had developed and first started production of the C-17 at the site in 1991. Boeing bought that firm in 1997, taking over the Globemaster III program and the production facilities in the process.

Before that, the Long Beach plant had a storied history stretching back to World War II when the Douglas Aircraft Company received a contract to build late-model Boeing B-17 bombers to support the war effort. Aircraft production at the site continued after the war and the hangars and production lines churned out McDonnell Douglas MD-80 airliners in the 1980s.

Though Boeing still provides C-17 related maintenance and other services in Southern California, the production facilities at Long Beach have been idle since the last Globemaster III left the plant in 2015. With the U.S. Air Force looking to expand its airlift capability, there had been talk of whether the production line might start up again, but this is a virtual non-starter, as The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway recently explained in depth.

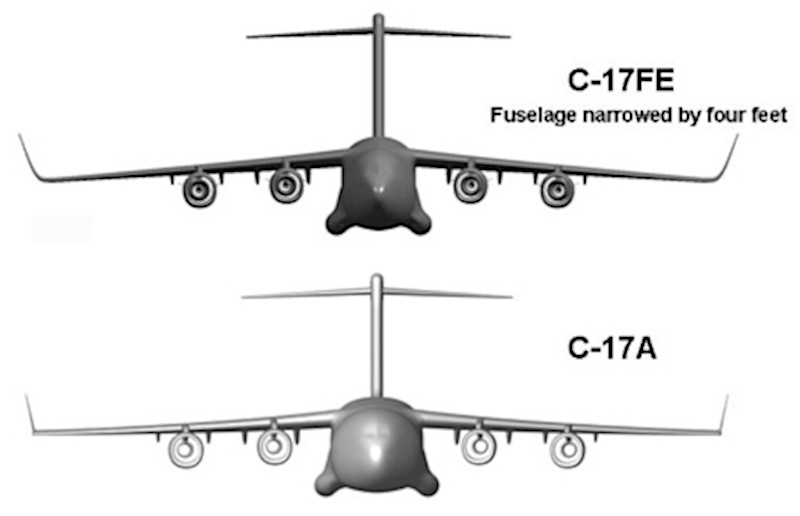

Even when the RAND Corporation conducted a detailed analysis in 2012 of what it might cost to reboot C-17 production after a multi-year pause – close to $8 billion to support the production of up to 150 new derivatives with improved fuel efficiency – the think tank assumed that Boeing would build those planes somewhere else rather than Long Beach. As early as 2008, the plane maker had largely decided that it was not cost-effective to keep the Southern California plant open for any purpose after it built the final Globemaster III, according to a separate report from the Government Accountability Office.

Boeing won’t solicit the first round of official bids on the property until the beginning of December 2018, NKF Capital Markets told the Los Angeles Times. As such, we don’t know who might be interested in taking over the expensive space on offer.

Interest from space launch firms that might see immediate value in the large hangars and other workspaces the site already has, is one a distinct possibility. In 2012, Boeing sold off Douglas Park, another portion of the former McDonnell Douglas complex, to real estate developer Sares-Regis Group.

Virgin Orbit, a division of billionaire Richard Branson’s multi-national Virgin Group business empire, is now headquartered in that office park. This company is developing a capability to launch small satellites into orbit using an air-launched rocket called LauncherOne and a modified Boeing 747 airliner known as Cosmic Girl.

Cosmic Girl will carry LauncherOne under its wing using a pylon attached the plane’s existing mounting hard point under port wing, which it has in order to be able to ferry spare engines from one location to another. You can read more about the aircraft and that capability here.

On Oct. 24, 2018, Virgin Orbit attached LauncherOne to Cosmic Girl for the first time for a fit check ahead of a planned first launch sometime later in November 2018. This event occurred at Long Beach Airport.

With all this in mind, Virgin Orbit might be interested in expanding its footprint near the airport and gaining larger aviation-related facilities that might be well suited to its operations. Branson would certainly have the funds to make a competitive offer to buy the old C-17 production site.

But the private space launch sector, including companies focused on more traditional rocket launches and firms looking to develop lower-cost, air-launched options, is growing in response to both private and U.S. government demands. SpaceX, headquartered in nearby Hawthorne California, might be another interested party.

There’s always the possibility that a real estate firm or some other corporation might turn the space into an office park. Google purchased the hangar that once held the Howard Hughes’ massive “Spruce Goose” flying boat in Los Angeles’ Playa Vista neighborhood and is in the process of turning it into office space, as well.

The City of Long Beach itself has been looking to acquire the area as part of an urban revitalization project called the “Globemaster Corridor,” according to the Long Beach Press-Telegram. This would see the property become a sort of hybrid commercial-public area complete with parks and other recreational spaces.

“We are evaluating options for the future of the site in the best interest of Boeing and the community,” C.J. Nothum, a Boeing spokesperson told the newspaper in June 2018. “There are details at this point we can’t disclose.”

It will be interesting to see whether the property will continue to be connected to the aerospace sector or whether it will retain that link in name only. Whatever happens, it seems clear that Boeing has no intention of building C-17s at the plant ever again.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com