After more than five decades of steady service, it’s safe to say that Lockheed Martin’s C-130 Hercules family, as well as the civilian L-100 and now LM-100J models, has proven to be an especially versatile design. Its widespread use has prompted a whole associated industry of third party upgrades and add-ons, including one modular system called the Special Airborne Mission Installation and Response (SABIR) in particular, that can turn the aircraft’s rear paratrooper doors into surveillance arrays, communications nodes, even a radio and television broadcast antennas and more.

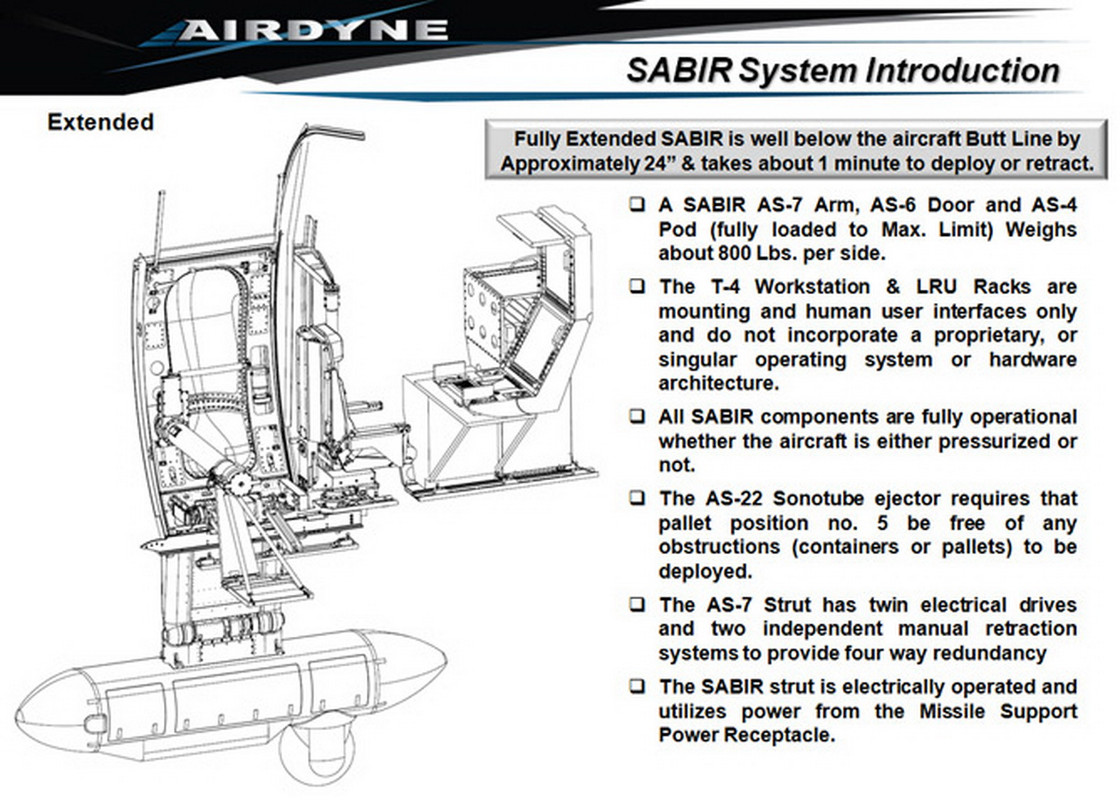

Airdyne, an engineering firm based on Calgary, Canada, has been actively developing SABIR, one of the better known systems, and expanding on what it can do since 2007. Its subsidiary, Airdyne Aerospace, handles the sales and marketing of the equipment, as well as repairs, from its headquarters in Florida. Rather than one single piece of equipment, SABIR is a modular kit that includes a new door, a retractable “arm” able to carry a store weighing up to 400 pounds, and an equipment rack and work station with a seat so a member of the crew can operate the systems now attached to the aircraft.

Relatively easy and quick to install, crews can substitute the rig for either the left or right rear paratrooper doors on any C-130, or both. Airdyne’s website says it initially developed the setup for the Hercules specifically, but that it is “platform independent” and able to fit on other aircraft, though the Hercules still appears to be the primary platform.

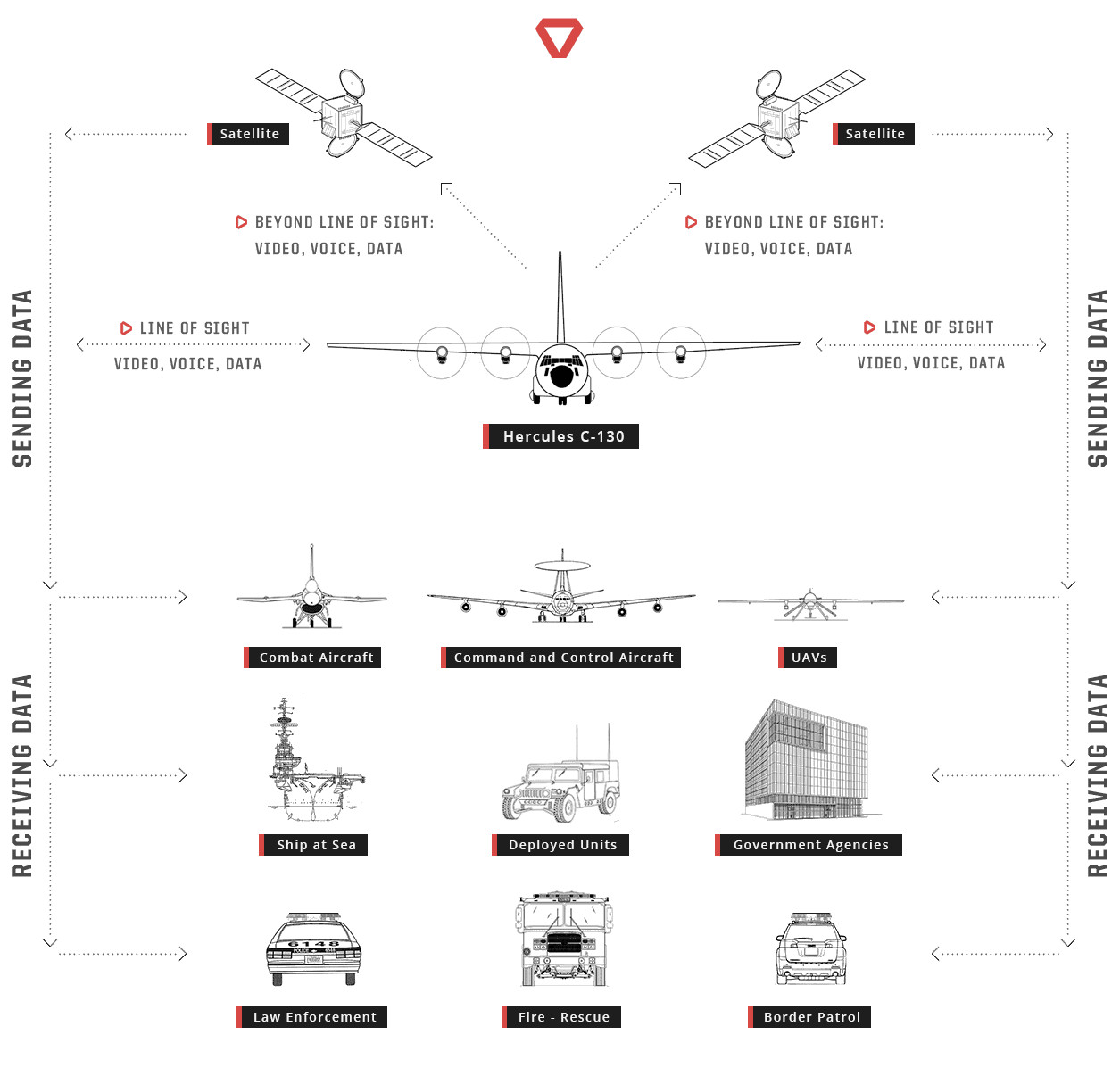

The company says that an aircraft with this rapidly reconfigurable kit could be useful in a variety of military, law enforcement, and civilian roles. Its website lists more than a dozen possible mission sets, including surveillance missions, border patrol, search and rescue, and scientific research.

Airdyne itself offers a number of modular pods that fit onto the extendable strut, the AS-4 and AS-18, both of which can accept a variety of different sensors, including electro-optical and infrared still and video cameras, imaging and surface search and surveillance radars, laser imaging equipment, and signals intelligence suites. Another option is a wide-area surveillance system that incorporates multiple video cameras to capture imagery across a large swath of land or sea. Analysts can then put imagery together in a large mosaic making it easier to spot routine patterns of enemy movement or changes to the landscape over an extended period of time. Multiple users can exploit different parts of the imagery at one time, and vehicles and even people can be tagged tracked, including “rewinding” past footage and tracing their steps over a period of time.

With the retracting arm, which only takes approximately one minute to extend or fold back up, the crew can position the pod well below the aircraft’s fuselage, as well. This reduces physical obstructions and other interference that might limit the range, field of view, intensity, or other capabilities of the sensors on board. Airdyne says that the full SABIR system works with nearly 170 different sensor packages.

We at The War Zone have written numerous times in the past about the immense value of modular sensor packages, especially for cash-strapped military forces and civilian agencies who might have limited numbers of actual aircraft available, but the need to perform a wide variety of missions. In July 2017, while exploring the U.S. Air Force’s new AgilePod system specifically, I wrote:

“This level of modularity makes perfect sense. If the AgilePod works as intended, during actual operations, crews on the ground could quickly swap out gear to better fir the situation at hand rather than having to prepare an entirely different aircraft or even just install a completely different pod. This would reduce the total number of aircraft a unit might need to be able to perform the different mission sets, as well as potentially speeding up the process of getting the appropriate equipment into the air. It would be especially useful for units at forward locations where existing infrastructure and resources may be otherwise limited.

…

“Of course, individual manned or unmanned aircraft would only be able to perform the missions that the pod is configured for at any one time. However, the multiple stations inside the AgilePod would allow it to carry more than one type of sensor during each mission, which would still provide additional flexibility over some existing configurations. ARFL already has a number of examples within the Air Force and elsewhere in the U.S. military it can look to for evidence of the benefits of similar modular architecture.”

So it’s not surprising that SABIR is already in service across the U.S. military, including with the U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy, as well as U.S. Special Operations Command and the Air National Guard. A number of other countries around the world also operate the system. The Air National Guard in particular has been steadily exploring the versatility of the concept to handle less typical missions.

In 2006, the New York Air National Guard turned to Sandia National Laboratories to develop an X-band radar for its LC-130H Hercules, already specially configured to support U.S. government activities in extreme cold weather locales such as Greenland and Antarctica. The 109th Airlift Wing had suffered a number of accidents when crews tried to land on what appeared to be stable ice, only to have the aircraft run into a hidden crevasse.

With the X-band radar, crews could see beneath the top sheet of ice and make sure their impromptu runway was safe before touching down. The 109th used SABIR to attach the equipment to the aircraft.

Afterwards, in cooperation with the National Science Foundation and Colombia University, the unit began helping test the “IcePod,” which could carry the radar, along with various other sensors for research purposes. The final design had multiple visual and infrared cameras, radars, and a GPS navigation system, and was able to gather data on ice depth and density and air and surface temperatures, among other information.

The Pennsylvania Air National Guard’s 193rd Special Operations Wing also had a unique requirement, but one that didn’t involve sensors at all. The unit flies the EC-130J Commando Solo variant, a psychological warfare platform that can beam out propaganda radio and television broadcasts over warzones, urging civilians to avoid certain areas or implore them to give up any support they might be giving to the enemy.

The only problem was that the Commando Solo conversions were complicated, costly, and would only ever apply to a small fleet. In 2008, the U.S. military decided to trim back the planned fleet from an already paltry six aircraft, down to just three. This left the 193rd with three “slick” C-130 airframes, plus an additional spare, that it suddenly had no idea what to do with.

The unit subsequently combined SABIR carrying a pod with a version of a U.S. Army psychological operations broadcasting system. The cost-effective combination meant that these EC-130J aircraft, though less complex than the Commando Solos, could still transmit FM radio, analog and digital television, and even SMS text messages.

The psychological warfare mission highlights SABIR versatility beyond just modular sensor packages. Along with the broadcast equipment, the arm could just as easily accommodate a communications or data sharing hub to help pass information between friendly forces on the ground and in the sky. This could be an especially important capability for smaller militaries that cannot afford to field dedicated aircraft for this mission, such as the U.S. Air Force’s fixed wing E-11 or EQ-4B drone, both of which carry the powerful Battlefield Airborne Communication Node (BACN).

Off the battlefield, this capability could be especially useful for more civilian authorities, in particular during a natural disaster that disables a significant amounts the communications infrastructure, including emergency assistance hotlines, or knocks out large portions of the power grid in a particular area. A C-130 flying an orbit with a communications relay could provide a quick substitute system to get first responders and larger government disaster relief agencies back in regular contact with each other so that they can best direct their efforts and quickly share critical information about the overall situation.

With its 400 pound load capacity and a standardized bomb rack, the system could theoretically carry small munitions or other types of stores, as well. In a pinch, a C-130 with SABIR might be able to double as an attack platform or release swarms of small drones able to conduct their own myriad missions.

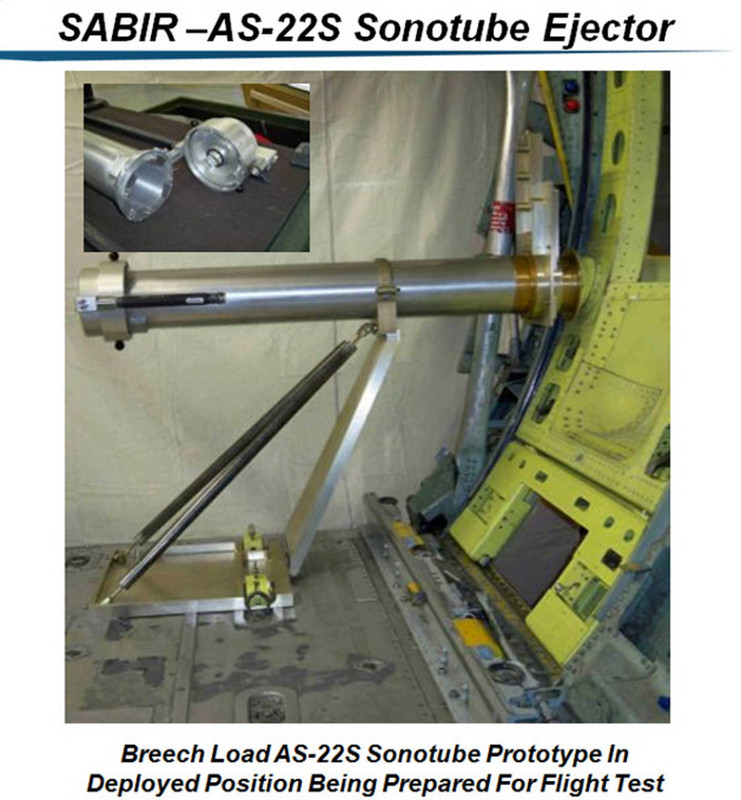

For maritime surveillance and anti-submarine work, Airdyne already offers a sonobouy launcher that fits into the new door. This doesn’t impede the ability of the system to carry other equipment, meaning that crews could have that capability plus a surface search radar for long range patrol operations over the open ocean just on one side of the aircraft. A second SABIR setup on the other size could carry additional sensors.

According to Airdyne, that same dispenser can accommodate other manually dropped payloads, too. These include the GBU-44/B Viper Strike lightweight glide bomb and small, expendable drones. It could also likely drop research probes, such as the dropsondes storm chasing aircraft drop into hurricanes and other extreme weather patterns to gather data on temperature, wind speed, and various other data.

It’s not the first time the U.S. military in particular has explored what it can do by simply swapping out the C-130’s rear paratroop doors. The U.S. Air Force Reserve flies two types of unique aerial spraying C-130s, both of which utilize that space.

In the 1970s, the Air Force first started using the Modular Airborne Firefighting System, or MAFFS, consisting of five pressurized tanks than can hold 2,700 gallons of fire retardant chemicals or water. The system fits inside the the main cargo area of a C-130 and dispenses the liquid over large forest and other wildfires through nozzles that poke out through the rear paratrooper doors.

In 2007, the Aero Union delivered the first improved MAFFS II, which replaced the five individual tanks with a single unit that also had a large 3,000 gallon capacity. In addition, the new system included two air compressors on board the aircraft, allowing the crew to pressurize the system themselves without the need for a separate piece of ground equipment.

In addition to MAFFS, the Air Force Reserve also has a small number of C-130s fitted with the Modular Air Spray System (MASS). This configuration includes spray nozzles fitted in modified paratrooper doors and under the wings. Unlike the fire-fighting MAFSS, MASS crews primarily spray chemicals to control harmful insects or invasive plants.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, the aircraft headed to Texas to help control a potentially dangerous explosion in the mosquito population. The planes have have also gone to work after other natural and man-made environmental disasters, including spraying oil dispersing chemicals in the Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion in 2010, which you can see in the video above.

In the 1980s, the Air National Guard began flyingh C-130s with a special signals intelligence system called Senior Scout, as well. While, the bulk of the equipment fit inside a container that slides into the main cargo bay, new paratrooper and landing gear bay doors held the antenna farm necessary to spot and monitor enemy emitters.

Ground crews could relatively quickly install all of the equipment onto any C-130 or remove it to put it back to work as a regular airlifter. The modular nature of the system meant that the Air Force built up a few versions, called Senior Warrior, for the U.S. Marine Corps to use on its KC-130 tanker transports during the first Gulf War. The Air National Guard appeared to have retired its remaining Senior Scout systems by 2013.

More recently, the U.S. Marine Corps added a new paratrooper door to its KC-130 fitted with the Harvest Hawk weapons kit. Nicknamed the “Derringer Door” for its two weapons launch tubes, crews could fire various lightweight precision guided munitions, include the GBU-44/B and the AGM-176 Griffin missile, from inside the aircraft. Earlier Harvest Hawks had a larger launcher on the rear cargo ramp, but that meant the crew had to depressurize the main cargo compartment in order to use it.

A Harvest Hawk could conceivably expand its capabilities by using SABIR to combine the stores release capability with a sensor or other additional equipment. At present, the gunships use a modular sensor turret system that fits onto the rear of one of the aircraft’s under wing drop tanks.

SABIR could also offer a quick, bolt-on electronic warfare capability, especially when combined with something such as the U.S. Marine Corps’ Intrepid Tiger precision jamming pod. Many of these systems can double as electronic intelligence suites since they have to be able to locate and monitor enemy signal sources. Intrepid Tiger itself makes use of so-called “open architecture” software that will allow engineers to quickly install upgrades and add new capabilities as time goes on, including potentially radar jamming and even the ability to launch cyber attacks.

In June 2017, Lockheed Martin unveiled a special operations configuration for the C-130J, the C-130-SOF. The concept art the company showed included a 30mm cannon firing through the left-side paratrooper door. This is a simpler, more modular arrangement than the purpose-built gun mount in the forward fuselage on the U.S. Air Force’s AC-130W and AC-130J gunships.

You really can hang a lot of stuff out of those rear paratrooper doors. More than six decades after its first flight, the C-130 is still going strong and it seems unlikely we’ve seen everything you can do with that space.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com