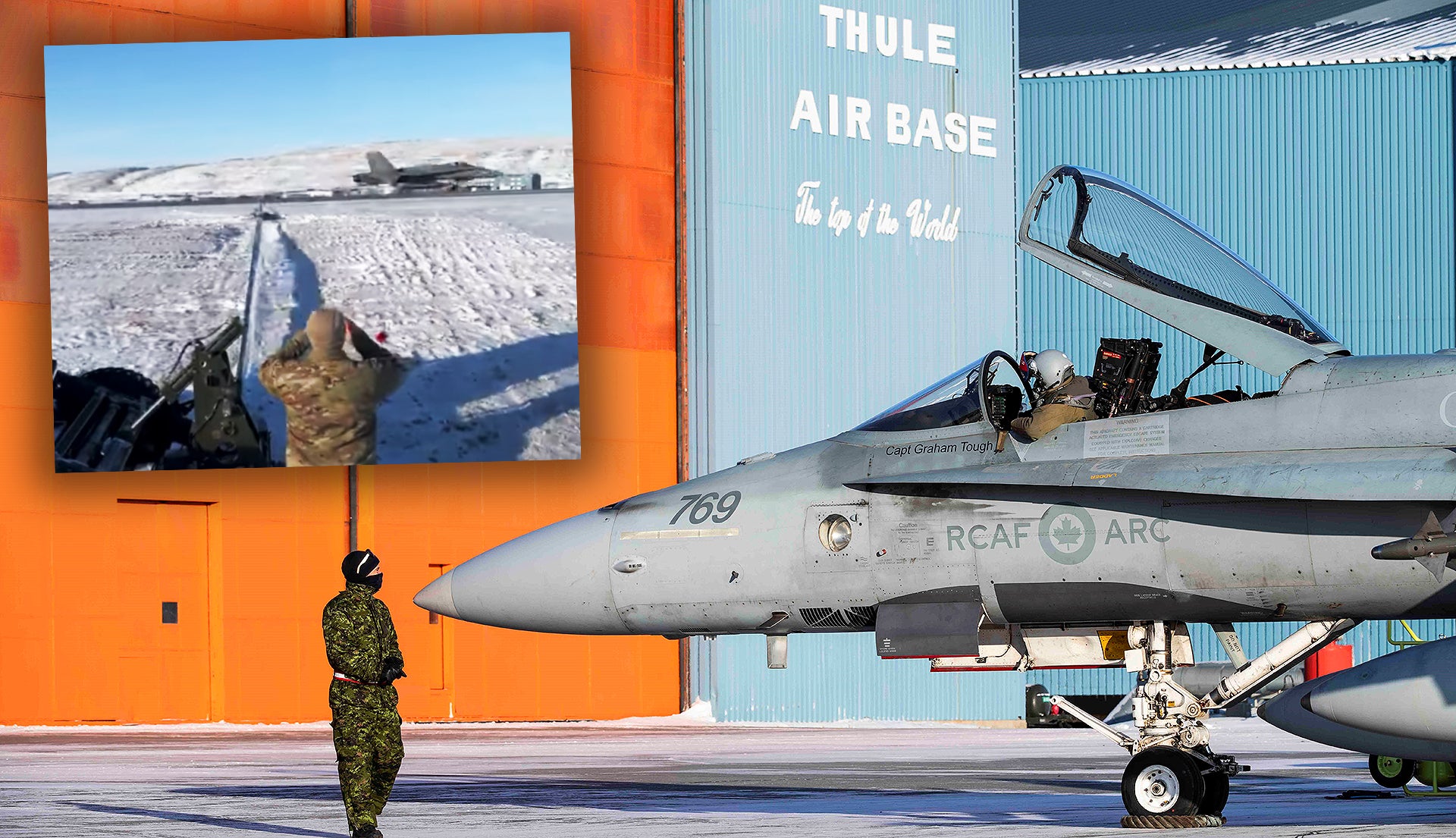

Royal Canadian Air Force CF-18 Hornet fighter jets have been operating in Arctic winter conditions at Thule, in Greenland, home of the northernmost U.S. airbase, an immensely strategic facility just 947 miles from the North Pole. The jets are helping prove the concept of year-round operations at the base in the High North, using the Mobile Aircraft Arresting System, which adds an important additional margin of safety for landing planes.

The U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) announced recently that the U.S. Air Force’s 820th RED HORSE Squadron — the acronym standing for Rapid Engineer Deployable Heavy Operational Repair Squadron Engineers — had installed the Mobile Aircraft Arresting System (MAAS) at Thule Air Base for use during the Amalgam Dart 21-2 air defense exercise. The U.S. Department of Defense confirmed that the MAAS was certified on March 21 via high-speed taxiing involving a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) CF-18.

“The system slowed a CF-18 from 128 knots to a full stop in 1,000 feet,” NORAD added. “The MAAS ensures we can support fighter aircraft ops in high Arctic environments.”

The MAAS is intended to be installed anywhere in the world where fighter operations may be required from short or icy runways or even those that have been damaged by enemy airstrikes. Similar equipment is also used to bring a fighter to a halt in an emergency situation. In the High Arctic environment, the MAAS gear reduces flight safety risks when recovering on runways that may be subject to snow, wind, and ice. At Thule, for example, winter temperatures can plummet to -47 degrees Fahrenheit, while winds reach as high as 100 knots.

Thule Air Base, where day-to-day activities are currently overseen by the fledgling U.S. Space Force, first began to be constructed in 1950 and its existence was revealed to the public in late 1952. Thereafter it hosted interceptor jets, as well as Nike nuclear-armed surface-to-air missiles to protect it from potential attack and to defend against Soviet bombers that were expected to head to the United States if a war between the superpowers were to break out. The full story of this unique airbase is something that The War Zone examined in depth in this past feature.

Since the Arctic winter at Thule presents more significant challenges to operations than most other airfields, concrete pads have also recently been installed there to allow rapid deployment of the MAAS throughout the year. When required, anchoring plates can be bolted into the concrete to then secure the MAAS.

According to the Air Force’s own manual on operating the system:

“The MAAS is a pair of mobile units, each unit consisting of a BAK-12 arresting barrier mounted on a mobile trailer. The BAK-12 arresting barrier brake unit is an energy-absorbing type system. Prior to the development of the MAAS, a fixed BAK-12 based system was used for expeditionary type installations; these systems required more than 100 man-hours to install and stopped aircraft within 950 feet. The MAAS was originally developed and tested to accommodate the recovery of fighter aircraft that had to return to a battle-damaged airfield. In its unidirectional configuration with a 90- or 153-foot cable, the MAAS can be installed in as little as two hours and stop fighter aircraft in a 990-foot or 1,200-foot runout zone. Each trailer contains the basic components of a fixed BAK-12 based arresting system and all the tools and hardware necessary for installation and removal, except for installation on soils with alow bearing pressure. The system is air transportable.”

Amalgam Dart 21-2, which is running from March 20 to 26, is a wider Arctic air defense exercise involving the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and USAF at various northern locations, including Whitehorse in Yukon, Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, Edmonton in Alberta, Goose Bay in Newfoundland and Labrador, plus Iqaluit, Nun, and Thule in Greenland.

Aside from the CF-18s from 3 Wing Bagotville, types taking part in the maneuvers include NATO E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), RCAF CP-140 long-range patrol aircraft, CC-130 search and rescue and tactical airlift aircraft, CC-150T tankers, and CH-149 Cormorant search and rescue helicopters; plus USAF F-16 fighter jets, KC-10 Extender, KC-46 Pegasus and KC-135 Stratotanker tankers, and C-130 and C-17 transport aircraft.

The area of the exercise extends from the Beaufort Sea off the north of Alaska, to Greenland and then south down the Eastern Atlantic to the coast of Maine.

The availability of the MAAS to provide year-round operations at Thule is significant. As we have discussed in the past, this airbase already serves as a vital outpost for early warning of a potential nuclear as well as providing a major logistical hub in a remote but strategically important region. MAAS-enabled fighter operations from Thule, within the context of Amalgam Dart, provides an additional operational node that helps expand the defensive bubble around the United States and Canada from aerial threats, even in the winter.

NORAD officials have spoken of wanting greater situational awareness against various potential threats, including cruise missiles, and extending defensive coverage further out into the Arctic supports that aim. “We don’t want to be in a situation … where end game defeat is our only option,” Air Force General Glen D. VanHerck, commander of NORAD and U.S. Northern Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee earlier this month, referring to the growing cruise missile threat from Russia.

Indeed, such is the strategic value placed on Greenland that President Donald Trump even said his administration was looking to purchase it from Denmark. That proposal, of course, was turned down by the Danish government, but the United States retains access to the strategic military outpost at Thule Air Base, now home to around 600 USAF personnel, civilian contractors, Danes, and Greenlanders.

The U.S. military, in general, is becoming ever more interested in austere airfield operations, in Europe, the Indo-Pacific, and elsewhere. There may also be an argument that the CF-18 is better adapted to these particular kinds of operations than some other land-based fighters, thanks to its pedigree as a carrier-capable jet, built for the rigors of arrested landings. The same would apply to the F-35C carrier variant of the Joint Stike Fighter, which the U.S. Marine Corps is now also testing for arrested recoveries on land, as well as at sea.

For its part, the ability to deploy detachments of fighters to the High Arctic, all year round, is a powerful counter to Russia’s increasing air and naval power in the region. Moscow, for its part, has been establishing new bases in the Arctic as well as stepping up its own fighter deployments to remote bases, including Rogachevo, in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago, which hosted MiG-31BM Foxhound interceptors earlier this year. According to the Russian Ministry of Defense, 19 airfields of this kind have been repaired or reconstructed in the Arctic in recent years.

As well as being the likely route for a potential attack on Canada or the United States, the Arctic also has great significance for its natural resources and shipping routes, both of which are being expanded as the polar icecap continues to retreat in the face of climate change. For this reason, the United States is also forging increasingly closer links to strategic partners in the region, including Norway, which is currently hosting its first deployment of USAF B-1B Lancer bombers, and Iceland, where B-2 Spirit stealth bombers operated from last year.

Thule Air Base can also serve as a stepping stone for offensive operations in Europe, especially in areas of Northern Europe just below the Arctic Circle. Thule could be a valuable base for land-based anti-submarine and other maritime patrol operations, as well, which could in turn benefit from having fighter cover during a major conflict.

Previously, Russia was seemingly forging ahead when it came to expanding its military footprint in the Arctic. This latest exercise, however, with its promise of year-round fighter operations in Greenland, clearly points to America and Canada seeking to redress the balance.

Correction: The original version of this piece incorrectly stated that the RED HORSE squadron involved in the exercise was the U.S. Air Force’s 823rd Squadron. In fact, the MAAS was installed by the 820th RED HORSE Squadron, out of Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com