The U.S. Navy is once again conducting studies into what it might want out of a potential future class of light aircraft carriers, or CVLs. The service says it has already been looking at designs based on the aviation-focused America class amphibious assault ships and a “light” derivative of the new Ford class supercarriers, among others.

Navy Rear Admiral Jason Lloyd offered the update on the Navy’s light carrier initiative during an online talk that the American Society of Naval Engineers put on last week, which USNI News was first to report on. Lloyd is Naval Sea Systems Command’s (NAVSEA) Deputy Commander for Ship Design, Integration and, Engineering, or SEA-05. The Navy resurrected the basic idea of acquiring a CVL of some kind, which has come and gone numerous times over the years, as part of a questionably ambitious overarching force structure plan it unveiled last year. You can read more about that proposal, known as Battle Force 2045, in these previous War Zone pieces.

“Just because a decision was made 10 years ago does not necessarily mean that decision is the right decision now,” Lloyd said of the decision to once again look into a CVL. “When you’re looking at littoral warfare or you’re looking at great power competition, those are two different adversaries, and the weapons that you need to fight those adversaries might be very different.”

It’s not entirely clear when the Navy actively began exploring CVL possibilities again. The service had said it was eying light carriers again in March 2020, only to reveal that it had shelved that effort two months later.

Lloyd also said that the Navy had been looking at other designs beyond those based in part on the America and Ford class hullforms. “We’ve looked at various different options and done cost studies on all those options. There are also capabilities studies on all those options,” he explained.

Of course, it’s not necessarily surprising that the service has been looking at whether it might able to leverage its two most recent aviation-focused ships in any way in designing a new CVL. Doing so could help reduce the time it takes to finalize a light carrier derivative of either ship and help keep costs low by making use of existing construction processes and supply chains.

There has already been discussion about using the America class design as a potential starting place for a CVL, including here at The War Zone, and it presents certain immediate benefits for such a conversion. The USS America, along with its sister ship USS Tripoli, are categorized as amphibious assault ships, but lack well-decks traditionally found on such vessels, which are used to launch and recover hovercrafts and other types of landing craft. This has made the design heavily-aviation focused from the outset. The third America class ship, the future USS Bougainville, is the first example of a distinct subclass that will have a well-deck added.

The Navy, together with the U.S. Marine Corps, has already been experimenting with the nearly 46,000-ton-displacement America, as well as older Wasp class amphibious assault ships, in the so-called “Lightning Carrier” role featuring aviation components with larger than usual numbers of F-35B Joint Strike Fighters. You can read more about this concept in these previous War Zone stories.

At the same time, the Americas, which do not have catapults or arresting gear in their present guise, are still limited carrying to short takeoff and vertical landing fixed-wing aircraft designs, such as the F-35B, as well as helicopters and tiltrotors. They lack an angled deck configuration that would allow for simultaneous launch and recovery of traditional fixed-wing types, which would limit sortie generation capacity.

Carey Filling, head of the Surface Ship Design and Systems Engineering Directorate within NAVSEA’s SEA-05 office, who has also been involved in the light carrier studies and was on the same panel as Rear Admiral Lloyd at the American Society of Naval Engineers event, brought up the fact that a conventionally-powered CVL based on the USS America would also not have the range of nuclear-powered supercarriers, such as the Ford. Traditional carriers, compared to boxier amphibious assault ships, typically can reach higher speeds, as well. These seem to be among the reasons why the Navy has also been looking at a “light” version of the 100,000-ton-displacement Ford.

“I will say that we certainly learned that it is hard to beat the sortie rate of the Ford. The Ford is optimized for its ability to deliver aircraft and ordnance off the ship at a high rate, so it’s hard to match that,” Filling explained. “I think the other thing to think about is the range of a nuclear carrier, its ability to move somewhere quickly and its speed, is hard to match.”

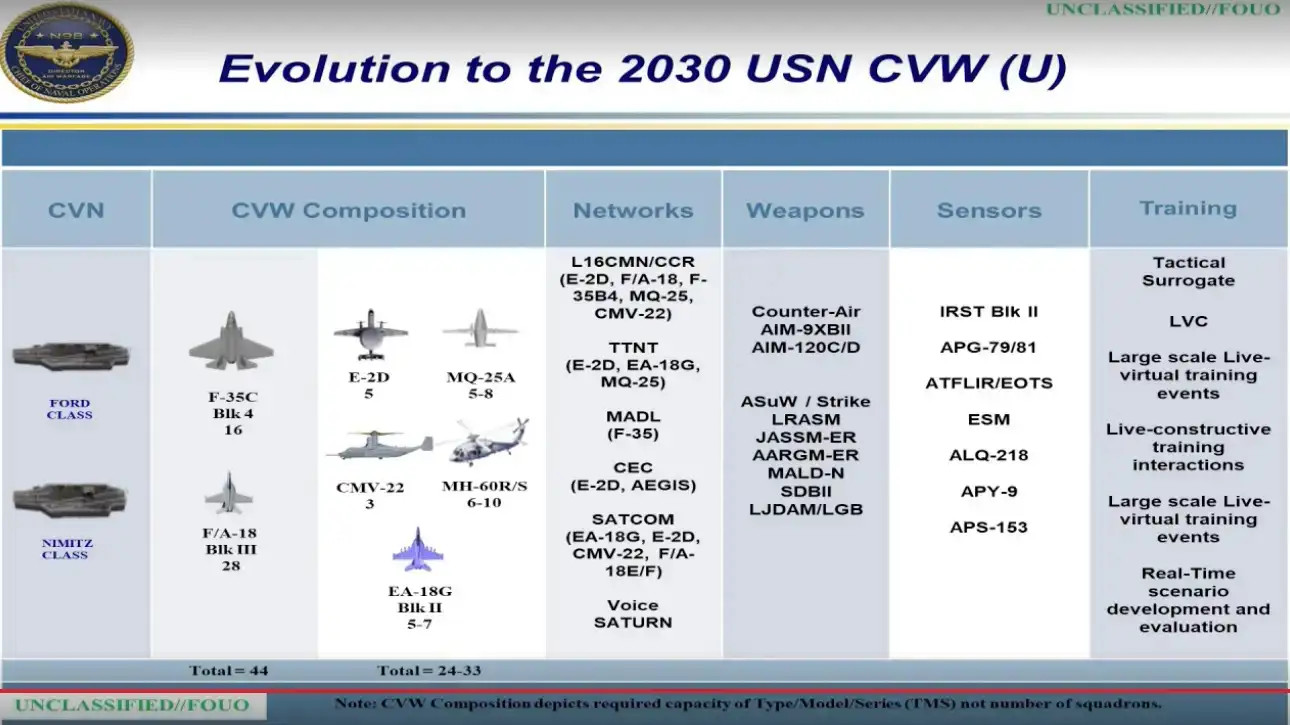

At the same time, Rear Admiral Lloyd acknowledged that more recent developments in aircraft design, especially in the development of unmanned types, including those capable of vertical takeoff and landing, could produce very different assessments of what a future CVL might actually look like. Historically, aircraft carriers, including the Navy’s own new Ford class, have designed around an air wing that is, by far, predominantly equipped with manned aircraft. The fixed-wing components of those air wings have generally utilized designs that take off and land like normal planes.

Crafting the air wing for a future CVL around a significantly greater proportion of smaller, unmanned designs, including ones that might not need a large amount of deck space to take off, land, or otherwise move about, would have significant impacts on the rest of the ship. More than a decade ago now, Lockheed Martin presented a concept for a stealthy, unmanned, vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, known as the Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) Advanced Reconnaissance Insertion Organic Unmanned System, or VARIOUS, which was intended to be optimized for shipboard operations and that could be configured to perform a number of different roles.

There have been a number of other relatively large vertical takeoff and landing-capable drone concepts that have come and gone since then, including the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Tactically Exploited Reconnaissance Node (TERN) and XV-24A LightningStrike programs. More recently the Marine Corps was exploring similarly unmanned aircraft, including Bell’s V-247 Vigilant tiltrotor drone, as part of its now-stalled Marine Air Ground Task Force Unmanned Aircraft System Expeditionary program, or MUX.

A future CVL could also be built around advanced unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV) that take off and land conventionally. There are already separate discussions about what additional roles the Navy’s future MQ-25A Stingray carrier-based drones might perform as time goes on. These unmanned aircraft will be primarily tasked with aerial refueling, at least to begin with, but the design as it exists now has a secondary intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capability, as well.

Of course, none of this precludes the Navy from investigating more traditional aircraft carrier designs that are just smaller than its existing supercarriers, including the Ford and its future sister ships, as well as the older Nimitz class types. The War Zone has explored in detail in the past how smaller carrier designs could offer significant benefits in operational flexibility, as well as lower operating and maintenance costs, all while providing additional naval aviation capacity. The latter point seems especially important as of late given the significant strains being placed on the service’s existing carrier fleets, which you can read more about in this past War Zone piece.

“An aircraft carrier in World War II is not the same as a Nimitz class carrier; there have been a lot of lessons learned over the years such as being able to do simultaneous launch and recovery, such as being able to safely maneuver aircraft once they’ve landed and still do simultaneous launch. So there’s a lot to an aircraft carrier flight deck that has been lessons learned over the years,” Rear Admiral Lloyd said. “So to go to a CVL light that we talked about has some tradeoffs. We say that it could be significantly less expensive, and it can be, it could be less expensive, but there are tradeoffs to that. So we have to go figure out what it’s going to be.”

It’s important to note that there’s also no guarantee that the Navy will ultimately pursue a CVL as a result of these new studies. The service’s overall Battle Force 2045 plan, which has not yet been formally approved, is now in at least a certain amount of bureaucratic limbo due to the change in Administrations from President Donald Trump to President Joe Biden. Biden and his new national security team, including Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, have already been taking fresh looks at various major defense and security issues that they inherited.

At least for the time being, the Navy is continuing to explore a future fleet that could include a new class of light aircraft carriers.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com