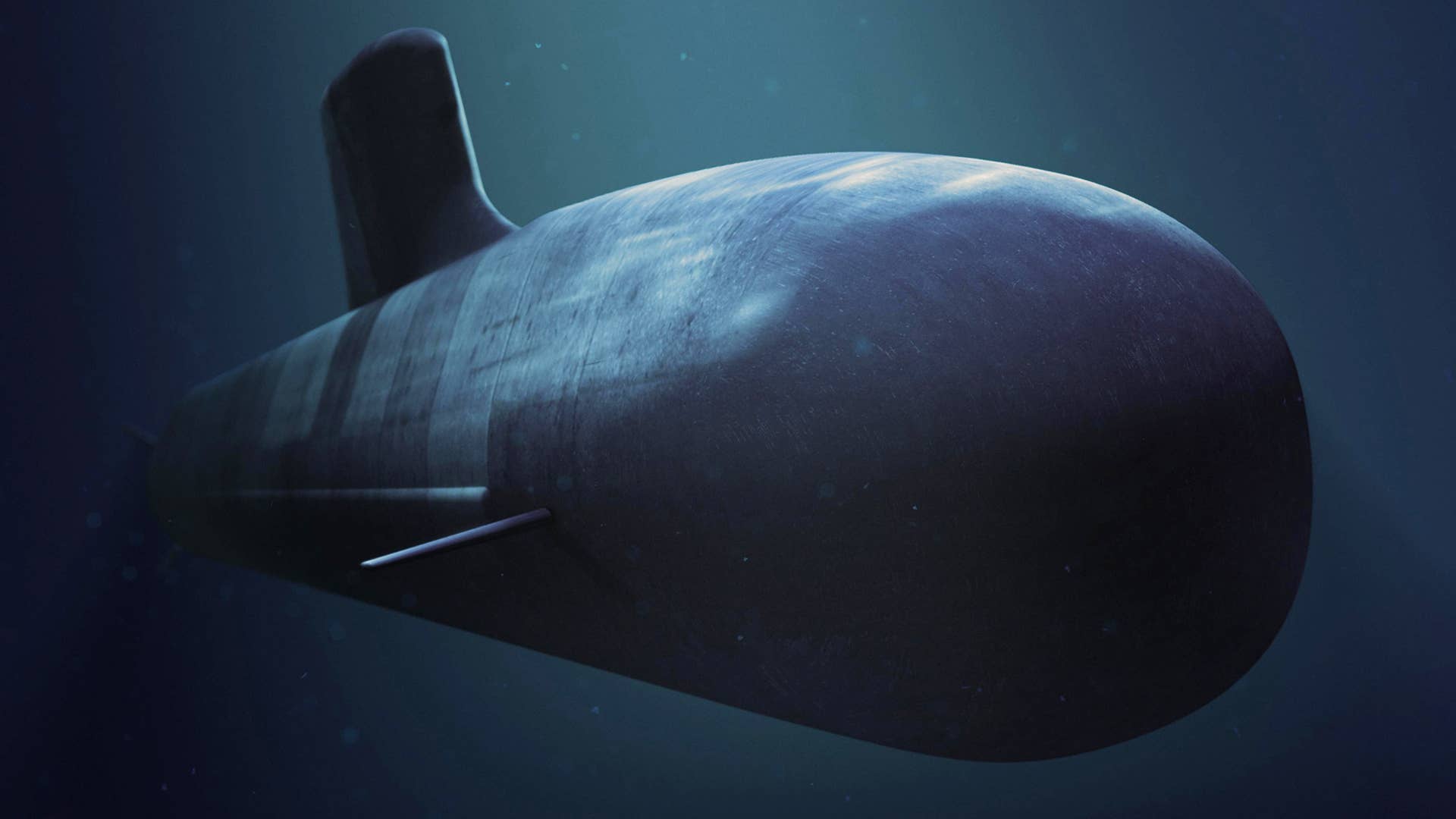

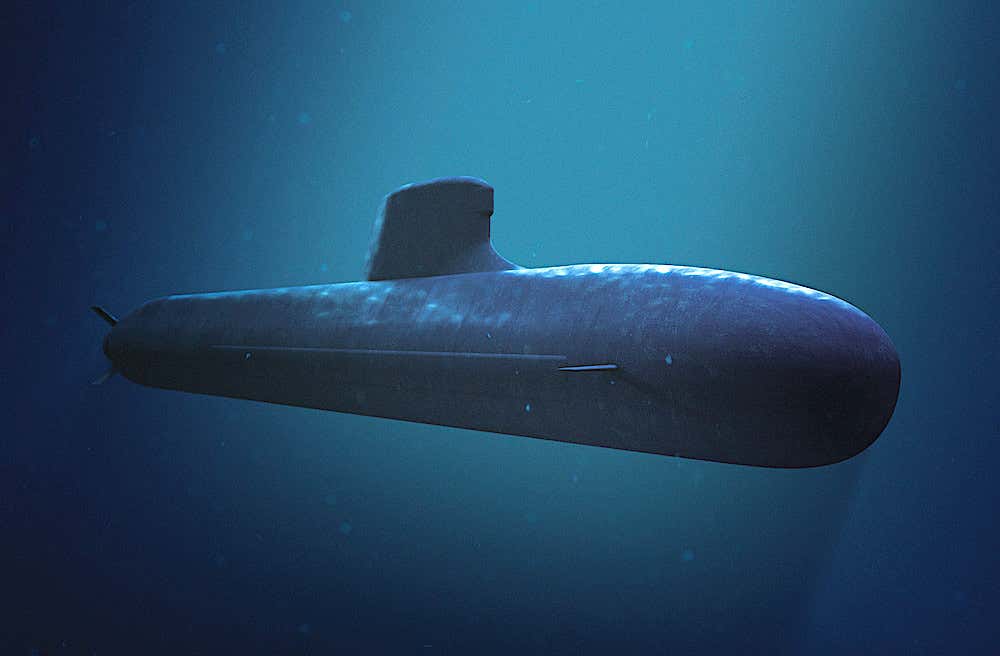

Australia’s plans to introduce 12 advanced new Attack class submarines may have hit a new snag. The huge cost of the French-designed conventional submarines, which will likely feature air-independent propulsion and other advanced technologies, means that officials may be examining whether they might instead replace the Royal Australian Navy’s six existing Collins class boats with an updated version of this same design.

The Australian Financial Review

recently reported that the Australian government is considering scrapping the current contract with French shipbuilder Naval Group. That conglomerate, then known as DCNS, won the Collins class replacement program, also known as SEA1000, in 2016 with its Shortfin Barracuda Block 1A design. You can read all about how the final stages of that competition played out, and the rivals to the French design, in this previous War Zone feature. Subsequently dubbed the Attack class, these submarines are presently due to enter service in the early 2030s and will feature a significant proportion of U.S.-made systems installed, including a version of the AN/BYG-1 Submarine Payload Control System.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is reportedly increasingly unhappy with the way the Attack class program has been run so far, with “cost blowouts and missed deadlines” leading to apparent tensions between the Australian Department of Defense and the Naval Group, according to the Australian Financial Review. The project is now valued at around $69 billion. Back in 2016, when the Naval Group was selected, the program cost was expected to be in the region of $40 billion. These concerns seem to have escalated as far as talks on the subject between Morrison and French President Emmanuel Macron. The French government holds a controlling stake in the Naval Group.

“I don’t think the [French] submarine is guaranteed to be built,” an unnamed source told the Australian Financial Review. “Naval Group is still holding the design work and intellectual property in France and the Commonwealth is annoyed.”

There are also worries about the involvement of the wider Australian industry, or the lack thereof. All 12 submarines are set to be built at the Osborne Naval Shipyard in South Australia. Under a Strategic Partnering Agreement, 60 percent of all the work on the program, by cost, was supposed to be invested in local suppliers. However, a commitment to this from both the defense department and Naval Group missed its deadline at the end of last year as negotiations continue.

“If Defence and Naval Group cannot reach a satisfactory contract amendment in a timely fashion for something that the company publicly committed to and is supposedly subjected to Ministerial oversight, then what confidence can Australian industry, particularly the small to medium enterprises, have that they will be able to compete in a fair and equitable manner for meaningful work on this program,” Brent Clark, Chief Executive Officer at Australian Industry & Defence Network, told the Australian Financial Review.

These are not the first problems that the program has run into. The original contract, and how the Australian government handled subsequent negotiations with the Naval Group, previously led to significant controversy and has been threatened in the past with a formal inquiry.

As an alternative to the Attack class, the Australian government is now apparently considering the possibility of having Naval Group Australia — a local subsidiary of the French designer — build a new class of submarines that would be based on the aging Collins class design, the first example of which entered service in 1996. Freeing the project of some of the controls of the French parent company could help bring down costs and otherwise increase transparency in the project, which involves one of the biggest international defense contracts in recent history. However, it is unclear how the alternative design would compare to the Attack class, and what compromises might have to be made in terms of capabilities and performance.

So far, the Attack class program has reached the detailed design phase, in which the winning Shortfin Barracuda Block 1A design are to be refined and plans and specifications for the Australian version drawn up. The Australian Financial Review says that while this phase was expected to cost $1.9 billion, this is now thought to have risen to $2.3 billion, contributing to the current concerns about the overall feasibility of the project.

“As work on the design of the Future Submarine progresses, Naval Group are finalizing their proposal for the next phase in cooperation with [the Australian Department of Defense] Defense to ensure uninterrupted work on the Attack class,” a spokesperson for that department told Australian Financial Review in a statement.

Should Australia now turn to an evolved Collins class design — known informally as the “Son of Collins” — it would rekindle its relationship with the Swedish firm Kockums, whose parent company Saab now owns the design rights to the submarine. For their part, Saab/Kockums was not among the companies involved in the final bidding for the Collins class replacement, but they have plenty of experience building advanced conventional submarines, including the much-vaunted Gotland class. This design, which also features an air-independent propulsion (AIP) system, was built for the Swedish Navy and one example was leased by the U.S. Navy in the mid-2000s as a dedicated aggressor.

The “Son of Collins” idea is not new. Back in 2015, before narrowing down the Collins class replacement program to three contenders, the Australian Department of Defense rejected a revised Collins class design on the ground that it was not worth the cost and risk involved. Furthermore, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, it was considered that Kockums “weren’t up to the job since they hadn’t built a submarine for many years.”

Now, however, Australian Financial Review reports that Australian Defense Minister Linda Reynolds has not denied the possibility of beginning talk with Saab about a potential alternative to the Attack class. “As the original designer of the Collins class submarine, Saab Kockums has an ongoing relationship with [the Australian Submarine Corporation] supporting the life of type extension program for the Collins class submarine,” she said.

Kockums is also still involved in the Royal Australian Navy’s submarine program, providing ongoing support for a life-extension program that is intended to keep the original Collins class boats viable until their planned successors are in service. As such, a relationship between the two firms that could field an alternative to the Attack class is already in place.

There may be other customers in the market for just such an evolved Collins design, too. Saab is currently in the running to supply the Netherlands with a new submarine class and that country has broadly similar requirements to the Australians. Were both Australia and the Netherlands to opt for this “Son of Collins” design, both could benefit from the resulting economies of scale.

The Royal Australian Navy badly needs an advanced submarine to ensure the security of its strategic sea-lines-of-communication in an Indo-Pacific region with no shortage of potential flashpoints and chokepoints. As Australia invests in its military to maintain a qualitative and quantitative edge over its regional rivals, its submarine fleet will be expected to conduct missions such as patrolling the South China Sea, where a fast-growing People’s Liberation Army Navy is increasingly assertive both above and below the water.

The sheer cost of the Collins class replacement program has always been eye-watering, but the total includes research and development, integration of combat systems, setting up indigenous production, and support infrastructure, meaning that a price tag of $8 billion per hull is not strictly accurate. That doesn’t necessarily mean that Australia made the right choice to start with, however. Back in 2016, when Naval Group won the contract, The War Zone’s Tyler Rogoway commented:

“The truth is that diesel-electric submarines with advanced AIP capability can be had for around $500-$700 million a boat if bought directly from a manufacturer such as Germany’s Thyssen Krupp. Even Israel’s highly modified Dolphin II class of submarines cost around $500 million each. But the Shortfin Barracuda is a much larger boat than the Dolphin II and is packed with additional combat capacity and features. Most importantly, it will end up being a relatively new design built in an entirely different country than its origin. It will also feature American combat systems.”

The size of the Attack class certainly contributes to its cost. However, the Royal Australian Navy is familiar with operating larger submarines. The current Collins class has a nearly 3,500-ton displacement, while the Attack class is planned to have a displacement of over 4,000 tons. Although exact specifications are not yet available, the French-designed submarines will be around 295 feet long, compared to 254 feet for the Collins class. On the other hand, the rival German Type 216 submarine that lost out in the SEA1000 bidding would have cost half as much but would have been comparable in size to the Attack class.

At this point, many of the details of the Attack class are yet to be confirmed. However, we can be sure that they will be tailored for operations at long range, with the ability to move at high speeds when necessary. The exact nature of the propulsion technology to be used is unclear, but there have been rumors the submarines may use French fuel cell systems. Consideration is already being given to new battery technology that could offer significantly improved performance and may potentially replace traditional lead-acid batteries, in the same way that Japan has opted for lithium-ion batteries in its latest class of submarines.

Ultimately, Australia demanded a submarine that was a close as possible to a nuclear-powered design in terms of capabilities, but with conventional propulsion. So in some ways, the most logical choice was the Shortfin Barracuda Block 1A, based on a scaled-down version of the nuclear-powered Barracuda design that is now entering French Navy service. That decision should result in a submarine that easily meets Australian requirements, but one that comes with a hefty price tag that seems disproportionate. France, for example, is paying a reported $10.2 billion for its six Barracudas, which, even taking into account subsidies, seems to be in a different league to the $69-billion Australian program. The addition of U.S.-made systems in the Australian submarines potentially also adds cost and complexity to the Australian submarines.

It now remains to be seen whether the Australian government is prepared to burden the costs of its highly advanced French-designed submarines, or whether it will be willing to trade them for a cheaper option.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com